The French Soldier

Millions of men were mobilized for the war, and illustrators often focused on an "everyman" to carry the message of their creations. Sometimes this was the poilu poilu, a fond but satirical characterization of the foot soldier as a "hairy beast," sometimes the permissionnaire, a soldier home on leave, sometimes simply the brave man fighting for France.

On loan from Brown University Library, Anne S.K. Brown Military Collection

Image permissions: Kislak Center for Special Collections, Rare Books & Manuscripts, University of Pennsylvania

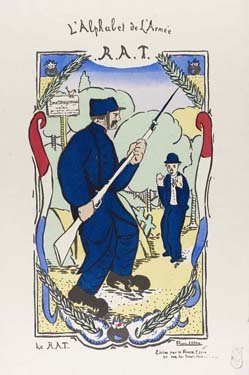

Just as the exact uses of these kinds of portfolios remain to be identified, the meaning of the abbreviations in Abadie's alphabet of vividly hued sheets is not always apparent today. The word rat in the French military was a pejorative term applied to persons in authority. But during World War I "rat" might also mean a base rat, that is, a soldier who stayed at base camp rather than going to the front. What does seem clear is that this poilu — a literal illustration of the slang term "hairy beast" — is preventing a civilian from entering a dangerous area. This confrontation has turned the trespasser into a cartoon convention of fear.

On loan from a private collection

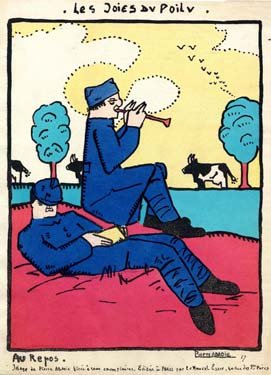

Two French infantrymen find a moment of repose in a bucolic landscape, one of them serenading cows with his recorder. The bells on the ends of the cows' tails ring in harmony as they march across the paper in a straight line. Like L'alphabet de l'armée, Les joies du poilu was published by Le Nouvel Essor. Abadie's style here has become deliberately crude and childlike. Were the six plates in this portfolio meant to satirize the French infantry, to humanize them—as they enjoy swimming, fishing, drinking, opening a parcel, departing for leave, or merely relaxing—or just to provide comic relief?

Guy Arnoux. Les Françaises. Paris: Devambez, [n.d.]

On loan from a private collection

Image permissions: Devambez; François-Jerome Arnoux, www.guyarnoux.fr

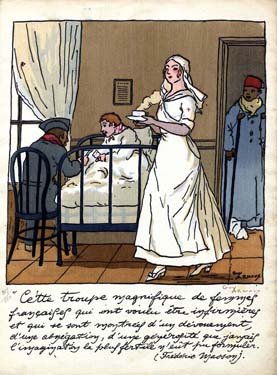

Arnoux's historical survey demonstrates that this conflict was not the first in which women provided support. Popular illustrations during the Great War portrayed women contributing to the war effort in a variety of ways—providing sympathy, moral support, and warm clothing; substituting for men's labor in vital industries, such as the manufacture of munitions; or, as here, serving as nurses. Interestingly, many images of nurses show them, in their white uniforms, with black troops conscripted from French African colonies. The bravery of such troops was legendary. Arnoux portrays a soldier with a bandaged foot standing with quiet dignity while the nurse performs her vital tasks.

Rare Book Collection, Gift of Neil Harris and Teri J. Edelstein

Image permissions: Devambez; François-Jerome Arnoux, www.guyarnoux.fr

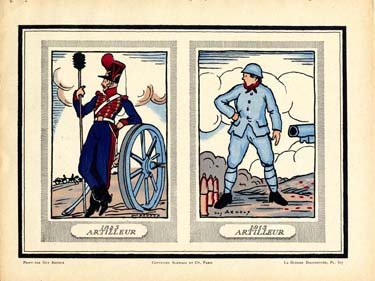

La guerre documentée (The War Documented) contains an explanation of the project: Guy Arnoux, the popular artist of the war, represented the poilus side by side with their warrior ancestors, showing them as worthy heirs. Arnoux, in fact, often depicted the soldiers of the Great War as more heroic than their predecessors, coupling a wary-looking grenadier with an incendiary device in 1716 against a 1917 grenadier forcefully throwing a grenade, a 1760 hussard (or houzard) at attention in dress uniform against his 1916 counterpart enduring rain on the battlefield, and here, an 1825 artilleryman elegantly lounging against his cannon while the soldier of 1915 stands ready to load the shells.

On loan from a private collection

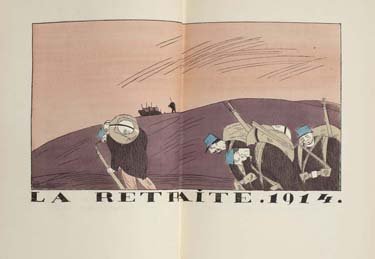

This book and its illustrations focus primarily on the amorous exploits of infantrymen during the war, but the conflict regularly intrudes upon their revelry. In "La retraite. 1914." exhaustion and despondency emanate from the bowed bodies of the trudging soldiers. Even the earth and sky seem suffused with blood. Martin's earlier illustrations from Sous les pots de fleurs are a point of departure for these depictions but, not surprisingly, they lack the immediacy of the earlier book. Martin and Astruc collaborated before the war but the contrast of subject is telling: an article in April 1914 on hats and umbrellas in the Gazette du bon ton.