“Don’t you feel fear?” a stoic Irina Shostakovich asked her rapt Chicago audience at Symphony Center. “Don’t you agree that fear exists in any society at any time?”

Madame Shostakovich, widow of the composer Dmitri Shostakovich, whose Symphony No. 13 (Babi Yar) anchors the Chicago Symphony Orchestra’s program this week, joined Music Director Riccardo Muti onstage for a post-concert conversation Friday. They spoke as much about the work’s interior movements — with titles like “Humor” and “Fear” — as its namesake opening elegy, which remembers the 1941 massacre near Kiev, Ukraine.

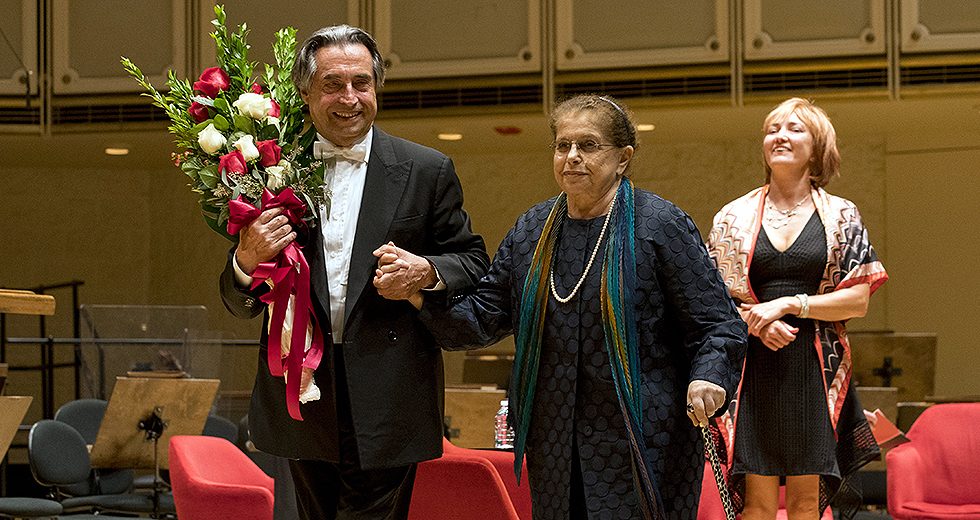

If the stately arrival of Maestro and Madame, Muti and Shostakovich entering arm in arm, evoked a regal portrait of memory and immediacy, the audience soon understood that World War II separated their childhoods. Her youth was shaped by the scarcity and tragedy of besieged Leningrad, now St. Petersburg; Muti was an infant in Naples, 2,000 miles away, when German forces surrounded Madame Shostakovich’s city.

“I love the entire [Babi Yar] symphony, but I am moved especially by the [third] movement that speaks about the Russian women — the sacrifice that they made,” Muti told Madame Shostakovich and the large audience, commending her husband’s setting of Yevgeny Yevtushenko’s poetic tribute, which reads: “They have endured everything; they will continue to endure everything. Nothing in the world is beyond them — they have been granted such strength!” (Yevtushenko, whose five poems Shostakovich set in his symphony, died last year at 83.)

Madame Shostakovich, who married the composer in 1962, lent her husband her own strength as his health declined; he succumbed to coronary complications in 1975. When an audience member asked if Muti might someday lead the CSO in Shostakovich’s final Symphonies Nos. 14 and 15, he wryly answered in the spirit of her sardonic spouse, “I can say, ‘Yes, I will do everything,’ then I go out and I have a heart attack and I die! … Life is very short. Art is very long.”

Madame and Maestro shared their satisfaction that Shostakovich’s Babi Yar, once censured for its stark portrayal of anti-Semitism, is now a staple of the Russian symphonic repertoire. “There was really a total silence after the [December 1962] premiere of the symphony,” she said to the Orchestra Hall crowd in Russian as a translator relayed her comments in English. After the premiere, which she attended, Madame Shostakovich remembered only a brief newspaper article acknowledging the work and noting “that this symphony is not appropriate for the system.”

More than seven years passed before Muti gave the symphony’s Western European debut, in Rome, early in 1970. He recalled working from the unpublished score, smuggled in on microfilm, surmising the composer’s tempos and dynamics from “no recording — nothing!” Nearly 50 years later, Muti still celebrates Shostakovich and the turbulent symphony a young conductor championed: “The person that criticized, as is written in the text [of the symphony], has disappeared and the person that has been criticized will remain forever.”

Even so, Madame Shostakovich admitted to bemused, if gradually subsiding, doubts about Babi Yar’s reception, evoking the reflection, humor and fear that characterized her late husband’s final symphonies — if not his entire lifetime. She wondered whether today’s American audiences might truly understand the work.

“There is a belief that Americans are too concerned about their own lives.” (“Sorry — just translating,” her onstage assistant chuckled, with Madame smiling.) “But during tonight’s performance I saw how people were reading the program, how they reacted to the music, how they were really deeply moved by this symphony, so I changed my opinion. I got plenty of positive feedback from the audience this evening. Spasibo.”

Andrew Huckman is a Chicago-based lawyer and writer.

TOP: Riccardo Muti escorts Irina Shostakovich from the stage Friday, after a post-concert talk. | Todd Rosenberg Photography 2018