In 2008, Gramophone magazine assembled a panel of leading music critics to choose the world’s top 20 orchestras — an ultimately impossible yet nonetheless thought-provoking assignment. Of their picks for the top 10 slots, two — Amsterdam’s Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra and Munich’s Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra — were led at the time by the same conductor: Mariss Jansons. It was an extraordinary endorsement of his elevated standing in the symphonic world and his ability to take great orchestras and make them even better.

Because of the heavy commitment of time and travel that overseeing both these ensembles required, Jansons gave up his post with the vaunted Concertgebouw Orchestra in March 2015 after nearly 11 years — a tough decision. “It was very hard,” he said. “We had a wonderful relationship with orchestra. The orchestra had a great development. It was always a first-class orchestra, but it was now very high class.”

But he continues to lead the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra, which will perform April 17 as part of the Symphony Center Presents Orchestra Series. On the program is Shostakovich’s Symphony No. 7 in C Major, Op. 60 (Leningrad). The afternoon concert (which starts at 4 p.m.) will be part of the ensemble’s third North American tour under the leadership of Jansons. The orchestra will begin its six-city itinerary April 12 at the Kennedy Center in Washington, D.C., and conclude with two concerts April 19-20 in New York’s famed Carnegie Hall.

Touring is good for any orchestra, Jansons said, because it challenges and inspires musicians by taking them out of their everyday routine and giving them the responsibility to represent their country and city elsewhere in the world. “It’s interesting to know how the music life is in different countries of the world,” said Jansons, 73, who was born in Latvia. “It’s like if you are in your flat all your life and you never see what is outside; it is very boring. [Touring] gives a lot of inspiration, and then you are playing in different halls with different acoustics, and you must adjust to this acoustic.”

Jansons was invited to be chief conductor of the Bavarian Radio Symphony after leading it just once. So he asked for an additional opportunity to conduct the orchestra to be sure it was a good match. By the break during the first rehearsal, he knew that he wanted to be at the helm. “They are very musically intelligent people, very spontaneous, very emotional, very dedicated to music and want the best quality,” he said. “It’s a top-class orchestra.” He became music director in 2003, and his most recent contract renewal in 2015 extends his tenure through 2021.

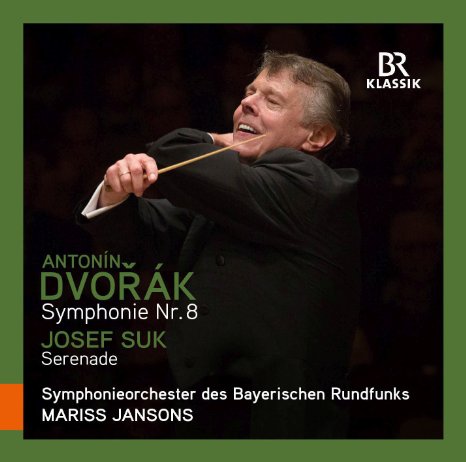

As is the case for the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, the Bavarian Radio Symphony records all of its concerts; for the BRSO, many are broadcast live on the radio. In addition, some of the stand-out recordings are released on the orchestra’s own BR-Klassik label. Its most recent release, available beginning April 8, is an all-Czech compilation that features Antonín Dvořák’s Symphony No. 8 in G Major, Op. 88, and Josef Suk’s Serenade for String Orchestra in E-Flat Major, Op. 6. (The Symphony No. 8 is featured on one of three programs that the orchestra is doing as part of its North American tour.) “It is very difficult, because you must try to do everything perfectly,” Jansons said. “It’s not like a studio recording, where you can repeat the same passage 10 times. Everything should be done well.”

Jansons spoke from St. Petersburg, where he has lived much of his life. Latvia was under the control of the Soviet Union when he left his native country at 14 to move with his family to St. Petersburg (then Leningrad), where his father was serving as assistant conductor at the Leningrad Philharmonic. He quickly enrolled at the Leningrad Conservatory and later continued his studies in Austria. Jansons was appointed associate conductor of the Leningrad Philharmonic in 1973 and took over as music director of the Oslo Philharmonic in 1979, significantly boosting its international profile before finally stepping down in 2000. In 1992, he was named principal guest conductor of the London Philharmonic, and five years later, he began a seven-year stint as music director of the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra.

In 1996, Jansons nearly died of a heart attack in Oslo while conducting the conclusion of La bohème. Surgeons later inserted a defibrillator in his chest, and the conductor describes his current health as very good. “I am now completely like a new man,” he said.

The works of Dmitri Shostakovich, Mariss Jansons says, deserve to be more popular, because “he is a genius.”

Few conductors are more associated with the music of Dmitri Shostakovich than Jansons, who has recorded all 15 of the composer’s symphonies: a project that was completed in 2006 to mark the 100th anniversary of the composer’s birth. In an unusual departure, Jansons recorded the works with eight different orchestras over more than 15 years, including the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra. “Despite their cosmopolitan variety,” wrote Andrew Clements in the Guardian, “there is a remarkable consistency about the performances, a reflection of Jansons’ uncomplicated gifts as a conductor, his wonderfully lucid grasp of musical architecture and unfailing knack of getting orchestras to deliver precise, vivid playing.”

Besides sharing Shostakovich’s Soviet heritage, Jansons studied with conductor Yevgeny Mravinsky, considered one of the greatest of all Shostakovich interpreters, in St. Petersburg. “I adore this music, and I like him very much,” Jansons said of Shostakovich. “It has always been a great pleasure to play him, and I want orchestras in the world to really play his music so that he becomes one of the leading and most popular composers, because he deserves it. He is a genius.”

According to the conductor, Shostakovich’s compositions are very philosophical and profound, dealing, among other things, with the daily struggle for existence. Although there are glimpses of light and hope, it is predominantly dark music. “It’s very important to know that no one piece of Shostakovich ends with a victory,” Jansons said. Although the music draws heavily on the composer’s difficult life in the Soviet Union, Jansons believes that the more listeners hear it, the more they will realize that it offers a universal message. “Gradually, they understand,” he said, “that he is expressing not only his life, but he is expressing our life today as well.”

For the BRSO’s program in Chicago, Jansons has chosen Shostakovich’s Leningrad Symphony. Although the exact meaning of the work remains in dispute, what is clear is that Shostakovich dedicated the 75-minute work upon its completion in December 1941 to the city of Leningrad — four months after the beginning of the calamitous Nazi siege of the city. “I wanted the orchestra to play a [Shostakovich] symphony which is not played very often and which is not the most popular,” Jansons said. “People know it, but not as well as the Fifth Symphony or the Tenth.”

Presenting the massive symphony not only showcases the diverse qualities of the fine German orchestra, but it also pays homage to Shostakovich. “Of course, now he is more popular,” Jansons said, “but I think he still needs support.”

Kyle MacMillan, former classical music critic of the Denver Post, is a Chicago-based arts journalist.

TOP: Mariss Jansons has been chief conductor of the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra since 2003. | Photo: Terry Linke