Jason Moran, steeped in the blues, for ‘Looks of a Lot’

Jason Moran dreams big. Not yet 40, the pianist/composer/cultural explorer and musical storyteller carries within him visions that reach beyond the…

Prokofiev, Shostakovich and ‘the ethics of survival’

The Chicago Symphony Orchestra’s Truth to Power Festival celebrates the power of the artist to act as a beacon in…

Speaking Truth to Power, bringing music to the masses

Conductor Jaap van Zweden, music director of the Dallas Symphony and a favorite with CSO audiences, will lead the Chicago Symphony Orchestra in three weeks of concerts (May 22-June 8) focused on the topic of Truth to Power and devoted to the music of Dmitri Shostakovich, Sergei Prokofiev and Benjamin Britten. From the 1930s through the 1950s, Shostakovich and Prokofiev found themselves ensnared in the convoluted cultural politics in their homeland of the Soviet Union, while British composer Britten, a pacifist during the early years of World War II, faced personal pressures. “These three composers had their difficulties, but they were all different,” van Zweden said. “All [faced] difficult moments in their lives. In dirt, sometimes very beautiful flowers grow.”

Reconstructing Shostakovich

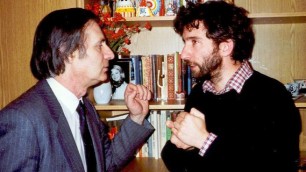

This spring, the Truth to Power Festival focuses on the music and actions of composers Dmitri Shostakovich, Sergei Prokofiev, and Benjamin Britten. Shostakovich provides a particularly interesting case – in addition to his already large output of published works, so many of his works were either abandoned or lost, and then rediscovered. Gerard McBurney, a composer and arranger – and artistic programming advisor at the CSO – has been called upon multiple times to recreate Shostakovich’s lost or unfinished work. We spoke with him about his experiences in reconstructing some of Shostakovich’s compositions.

‘Pulcinella,’ Stravinsky’s ‘discovery of the past’

While the term “neo-classical” serves as highly useful shorthand for describing much of Igor Stravinsky’s output, he himself hated the…

Life, washing away with the ceaseless tide, in Britten’s ‘Peter Grimes’

Benjamin Britten set Peter Grimes, his first major opera, in a small fishing village that could easily be the seaside…

Prokofiev’s Fifth, pointing ‘the way to a radiant future’

Sergei Prokofiev spent the summer of 1944 at a large country estate provided by the Union of Soviet Composers as…

Stepping into a long-lost world of Soviet music

Studying in the Soviet Union during the 1980s was an invitation to a long-vanished world for Gerard McBurney, now artistic programming advisor of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. He writes: “I caught a glimpse of what it really takes for all of us — composers, performers, and listeners — to discover music, to make music, to understand music, to take music actively into our innermost selves. … Despite the manifold and heavy injustices and oppressions of that country and that society … or perhaps precisely because of them … the USSR was certainly a country — and this should never be forgotten — where the mystery of music had a chance of being understood.”

On this island: Britten and his native land

In the ’60s, the soundtrack of England and the age was The Beatles. But for those who loved a different kind of music, it was Benjamin Britten who shaped and colored the way we heard our world.

When Prokofiev came to Chicago

In 1917, businessman Cyrus McCormick Jr. met Sergei Prokofiev, encouraged him to come to the United States and thus launched a longtime relationship with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra.