The word “legendary” gets thrown around a lot, but in the case of Gennady Rozhdestvensky, it could hardly be more apt. Now 84, the Russian conductor made his debut at age 20, leading a production of The Sleeping Beauty at the Bolshoi Theatre, and has gone on to become one of the most respected figures in the field. He has made more than 400 recordings and led dozens of premieres, including works dedicated to him, by such noted composers as Sergei Prokofiev, Alfred Schnittke, Rodion Shchédrine, Dmitri Shostakovich and John Tavener.

“One of the main undertakings that has defined my work,” Rozhdestvensky said in Russian via e-mail, “has been acquainting the so-called ‘West’ [sometimes this term includes the countries of the East, and above all, Japan] with the music of Russia and the opposite process.” By “opposite process,” he means exposing to Russian audiences to lesser-known non-Russian music. Rozhdestvensky has, for example, conducted all of Shostakovich’s symphonies in Japan, and in Moscow, led a three-year cycle of 12 concerts titled, “Foggy Albion,” dedicated to English music, including all four symphonies of Michael Tippett.

Since making his debut in 1974 with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, Rozhdestvensky has returned more or less regularly since, including a set of performances of Charles Ives’ Symphony No. 4 in 1977 that the conductor considers a particular highlight. After a 15-year absence, he will rejoin the CSO on Feb. 5-6 for a pair of concerts featuring Shostakovich’s Symphony No. 1 in F Minor, Op. 10, and Symphony No. 15 in A Major, Op. 141 — the composer’s first and last statements in the form.

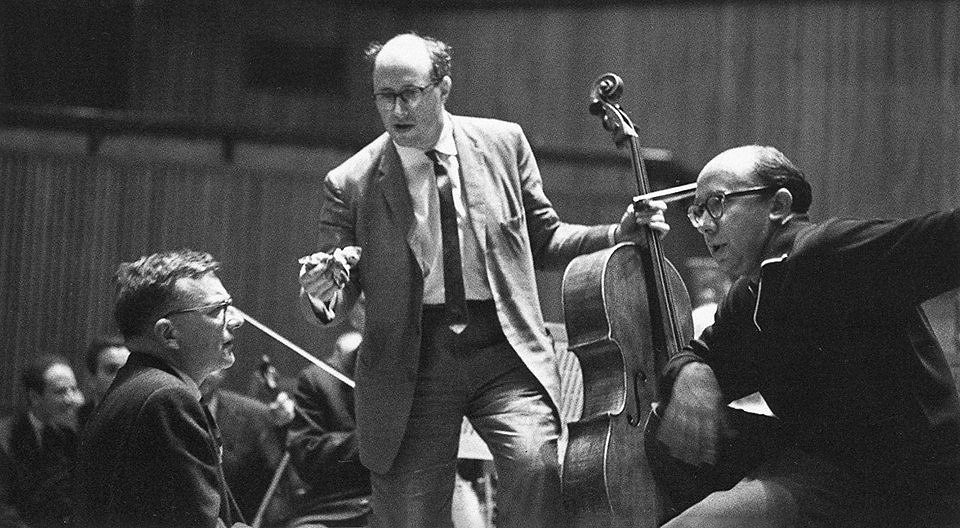

Dmitri Shostakovich (from left), cellist Mstislav Rostropovich and conductor Gennady Rozhdestvensky at a rehearsal for the composer’s Cello Concerto No. 1 in 1960.

Shostakovich wrote his debut symphony as a graduation piece at the Petrograd Conservatory when he was 19, and it was first presented by the Leningrad Philharmonic in 1926. The latter work was written in a little more than a month in 1971 and premiered a year later by the All-Union Radio and Television Symphony Orchestra with the composer’s son, Maxim, on the podium. Among other things, this final symphony is notable for its many musical allusions, including quotations from Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde and Der Ring des Nibelungen, and Rossini’s William Tell.

Although Rozhdestvensky does not recall the specifics of his first meeting with the composer, he believes it was during his early student years in the 1950s. “When for the first time,” he said, “I heard and saw in the score the phenomenal modulation in the Eighth Symphony of Shostakovich from G sharp minor to C major, in the transition from the fourth movement of the symphony to the finale, I understood that Shostakovich was a genius of a ‘special category.’”

Many musicologists have written books with varying takes on the Russian composer and the meanings of his dissident or not-so-dissident music, but Rozhdestvensky does not think any of these volumes has gotten it right. “Not yet, and it is unlikely that there will be such a book,” he said. “Though one would very much like one to appear!” Asked about the biggest misconception surrounding Shostakovich, the conductor pointed to an infamous Pravda article titled “Muddle Instead of Music,” published in 1936. It condemned the composer’s then recently debuted opera, Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk, now considered a masterpiece, as “coarse, primitive and vulgar”; the article signaled Shostakovich’s fall from official favor — a blow that nearly ended his career.

Over the years, Rozhdestvensky recorded all of Shostakovich’s symphonies with the USSR Ministry of Culture Symphony Orchestra and has led many performances of them with orchestras worldwide. His favorite among the 15 is the Symphony No. 4 in C Minor, Op. 43, which was written in 1935-36. Because of the denunciation of the composer’s music at that time in Pravda, Shostakovich chose to shelve the work, and it did not receive its premiere until 1961 – eight years after Joseph Stalin’s death. Rozhdestvensky led the Western debut of the piece at the Edinburgh Festival a year later.

“It would be difficult,” the conductor said, “to over-estimate the significance of my relations with Dmitri Shostakovich and Alfred Schnittke, in that these two titans opened before me a musical universe, like a gigantic magnifying glass reflecting our fragile world.”

Throughout his career, Rozhdestvensky has performed a great deal in the West, even becoming the first Soviet conductor to serve as principal guest conductor of such foreign orchestras as the Royal Stockholm Philharmonic Orchestra and BBC Symphony in London. But he nonetheless cites the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991 as the event that has had the most impact on the classical-music world during his lifetime. As a result, he said, “I achieved true freedom.”

Kyle MacMillan, former classical music critic of the Denver Post, is a Chicago-based arts journalist.