It’s the IMAX of stuffed cabbage, filling my whole field of vision, and the former Camilla Jessel is stunned by the scale of the chicken-liver schnitzel.

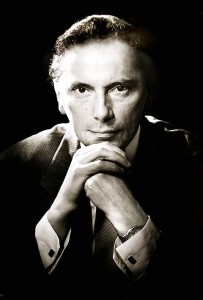

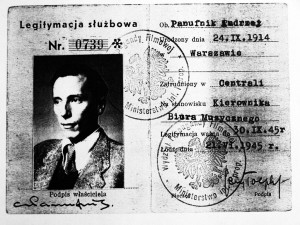

If interviews are about sharing and unburdening, our offal-heavy lunch looks promising. Half the wątróbka is launched at me with “Try THIS!” urgency and I’m tossing gołąbki right back at the wife of Sir Andrzej Panufnik, the esteemed Polish composer whose Concerto in modo antico the CSO will share with Warsaw audiences Monday, in the first of nine concerts on the orchestra’s 2014 European tour.

First in a series: Exploring ties between the CSO’s hometown and cities on its 2014 European tour

I’ve started with absolutely the wrong question and I’ll pay during the rest of this lunch. “When’s the right time for vodka at Polish meals, before or after?”

Lady Panufnik lends a playful grin. Her verdict (and my sentence)? “Throughout!”

“Put down in one gulp!” So bring on the Belvedere (a compromise). She says her husband “was very fond of a specific vodka called Żubrówka, and that has a piece of straw in it — a very highly flavored piece of straw — and it was the kind of straw that bisons like to eat.” But I’ve read “potentially toxic” Żubrówka is banned stateside and, truth be told, we’re in Chicago today.

She cheers Sir Andrzej, who died in 1991. “Let’s drink to his 100th birthday.”

I butcher “Na zdrowie!” and follow orders. Belvedere is no less lethal, at least this side of the table. But why is her glass just sips shy, which remains the case all afternoon?

To know the answer is to grasp the sharp wit and optimism that the self-exiled composer surely spied in the Kent-born Camilla, a mid-20s writer and photographer in mid-’60s London. Since 1991 the right to gracefully tease others with her glass half full carries the sanction of chivalry; the couple was bestowed with knighthood and ladyship in the composer’s final year.

It’s a tale reminiscent of Sir Georg Solti (1912-1997), the CSO music director who celebrated the Warsaw-born composer in 1982 and 1990 concerts that twice brought the Panufniks to Chicago. Solti, a Jewish native of Budapest whose 20th century paralleled Panufnik’s, fled west following the 1938 Nazi occupation of Austria. Solti likewise built his career in ’60s London, where he met 27-year-old journalist Valerie Pitts — Lady Solti to Chicagoans. Biographical affinities kept the Soltis and Panufniks close friends.

A Roman Catholic completing musical studies in Vienna when the Nazis arrived, Panufnik chose a fateful course east and returned home to Poland. His nightmarish wartime years, followed by the Iron Curtain’s cloak, which he fled in 1954 for London, shadow today’s spirited meal.

The fortune and irony of shuffling abundant portions plate to plate is never far from our minds. Lady Panufnik remarks on what we both know — in World War II Warsaw, destroyed and desolate, our meal would have been impossible.

Panufnik’s 1951 Concerto in modo antico, or “antique style,” which the CSO will perform in Warsaw with Principal Trumpet Christopher Martin as soloist, is part of what Lady Panufnik calls a collective postwar “restoration” of Poland’s physical and cultural heritage.

“Around 1950, the Poles, who were very unhappy under the Soviet yoke, started to feel they must rebuild some of old Warsaw and old monuments,” she says. “My husband was very inspired by this effort, and he thought that all the cultural background of Poland should be restored as far as possible, because everything had gone. The Nazis had flattened Warsaw and so many people had died.” Drawing from “fragments of old music,” he began “remaking these pieces.”

But Warsaw’s Soviet yoke drew tight. “He couldn’t live without composing. That was why he had to leave Poland — because everything he composed there was banned as being unsuitable for the great socialist Russian era.” After Panufnik’s Heroic Overture (1952) received a Warsaw “audition” — auditions kept composers in official check, Lady Panufnik explains — “one of the composers offered to burn the manuscript so that Andrzej should be free of this disgrace.”

“That was the last work he wrote under communism.”

A lonely, harrowed Panufnik reached London six years before he met Camilla. “He was very pessimistic. He thought that Poland would be dominated by the Soviets indefinitely. And he wouldn’t even let me learn Polish because he said it would be a waste of time — I’d never be able to go to Poland.”

The Polish composer instantly took to his Brit bride, who after they married in 1963, settled him into English habits — eschewing Żubrówka. “Every evening he used to drink a whiskey to calm down after composing.” And the couple attracted a celebrated English champion settling himself into Polish habits. The London-born (and American celebrity) conductor known as Leopold Stokowski — rumors surrounding his name’s authenticity still swirl — was a frequent and favorite guest.

Leopold Stokowski conducts the Philadelphia Orchestra circa 1940. He was a close friend of the Panufniks.

Lady Panufnik remembers that Stokowski (1882-1977) “rather carried things too far, because he tried to put on a Polish accent. And it was very funny to hear him putting on a Polish accent with my husband, who really had one.”

As for whether he found Stokowski’s diction convincing, Lady Panufnik offers, “Absolutely not! It was as fake as anything. But as a conductor he was not fake. He was an absolutely wonderful conductor. He was incredibly brave how he stood up for my husband in difficult times.”

Half a lifetime passed before Panufnik returned to Warsaw in 1990, the Eastern Bloc then a year past Soviet collapse and the ailing composer a year before his own demise. Little healed during his time away. Lady Panufnik, making her first trip to Poland, remembers the tragedy of a capital “still blighted by the poverty of communism, full of concrete buildings.” They found “an empty, gray, gray, gray, sad city.”

“It was quite a strain for him because they took us to find his father’s flat — the family flat — and it was no longer there. But it was not only the flat that was no longer there — the street was no longer there.”

Today Lady Panufnik appreciates that the Warsaw struggling so much of the 20th century is newly vibrant in the 21st. “It’s changed so completely now. It’s a wonderful and joyous place.” She recognizes a “sophisticated, Western capital city” and is sure Panufnik would be “incredibly happy to see what’s happened to his native country.”

He might find a Warsaw street he remembers, and one his compatriots won’t forget.

There’s a newly named lane in Mokotów, dedicated three days before this lunch, “a place that he must have passed along many, many times as a child,” running to the Pałac Szustra, “the house that belonged to his grandparents, which was destroyed in the war, but which was rebuilt.” It’s now a center “for young people to make music and give concerts and have music coaching. And so this road in his name, Aleja Andrzeja Panufnika, is a road to music studies. He would have loved this.”

Lady Panufnik was privileged to visit Warsaw for the street’s September dedication, as I am privileged to lunch with her this Chicago October afternoon. And she feels fortunate to return to Warsaw next week for the CSO’s concert. There’s a small club of accomplished women in classical music who’ve shared in their husband’s centennials — the stern Cosima Wagner marked Richard’s in 1913 and a mercurial Alma Mahler reached Gustav’s in 1960. London’s globe-trotting Camilla is the club’s dynamic new member, infusing her husband’s lifetime of challenge and struggle with relevance and optimism for his evolving homeland.

We’ve split strudel for dessert, but it’s just me this final wódka — “Na zdrowie!” — down the hatch, celebrating Warsaw’s courageous composer and his remarkable champion, keeping music and memory alive.

There’s a last playful grin with my emptied glass, a clap of Lady Panufnik’s hands and “bravo!”

Right back at both of you.

Andrew Huckman is a Chicago-based lawyer and writer.

Next in the series: Luxembourg in Portage Park.