This year marks the centennial of composer, pianist and conductor Andrzej Panufnik, once hailed by Sir Georg Solti as “the finest protagonist in the European tradition of music-making.”

Though perhaps as not well known as his near contemporaries Karol Szymanowski, Krzysztof Penderecki or Witold Lutosławski, Panufnik is no less significant.

Born Sept. 24, 1914, in Warsaw to a Polish father and English mother, Andrzej Panufnik grew up in a musical family. At age 9, he began composing and studied at the Warsaw Conservatory from 1932-1936, graduating with distinction. He then spent a year composing film music, after which he went to Vienna, where he studied conducting with Felix Weingartner while poring over the music of Second Viennese School composers Schoenberg, Berg and Webern.

For a few months, Panufnik lived in Paris and London, where he continued his studies. Weingartner urged him to stay in London because the European political situation was rapidly deteriorating. Panufnik, though, returned to his family in Warsaw. It was in that city, during the German occupation, where he and Witold Lutoslawski formed a piano duo that would appear in cafes because Nazi occupiers had forbidden any kind of organized gatherings, concerts included.

After WWII, music moved in many different directions: total serialism, chance music, and so forth. It was a heady time for composers, with plenty of dissonance and thick textures to go around — at least in the West, where musicians were constantly staking out new ground and exploring new worlds.

In the East, it was a different story. In the late 1940s, the Soviet Union decreed that composers should follow Soviet Realism – their music should reflect socialist life (whatever that meant). Soviet composers had to toe the party line if they wanted to hear their creations performed. Though Panufnik had become Poland’s leading composer, by 1954, he could no longer accept the burdens and restrictions placed on him by the state. He fled to London where he was granted political asylum (and eventually received a knighthood from Queen Elizabeth II in 1990). In Poland, he became a non-person and remained so for many years.

In the East, it was a different story. In the late 1940s, the Soviet Union decreed that composers should follow Soviet Realism – their music should reflect socialist life (whatever that meant). Soviet composers had to toe the party line if they wanted to hear their creations performed. Though Panufnik had become Poland’s leading composer, by 1954, he could no longer accept the burdens and restrictions placed on him by the state. He fled to London where he was granted political asylum (and eventually received a knighthood from Queen Elizabeth II in 1990). In Poland, he became a non-person and remained so for many years.

After the war, Panufnik wrote a good deal for film. For one of his movie scores, he used ancient Polish music, which he later transformed into his Concerto in modo antico, a work of Baroque charm and economy, scored for solo trumpet, two harps, harpsichord and string orchestra (which he composed in 1951 and revised in 1955). In it, Panufnik included elements of early Polish music. (The Chicago Symphony Orchestra will perform the work in subscription concerts Oct. 2-4, as well as on its upcoming European tour.)

“My compulsion to restore some of the early Polish music was engendered as I witnessed the superb reconstruction of beautiful 16th and 17th century houses in the old part of Warsaw, which had been flattened during the uprising at the end of the Second World War,” he wrote. “To see this almost miraculous re-growth of seemingly lost architectural treasures so lovingly brought about by my compatriots filled me with enormous admiration. I felt a strong desire to undertake a similar task with fragments of Polish vocal and instrumental music of the same centuries which had suffered near oblivion because of Poland’s long and tragic history of numerous foreign invasions. Little of this music survived in a performable state and I wanted to fill the gap, endeavoring to re-create as near as possible the true period style, like those ancient houses of Warsaw.”

His centennial year has brought many tribute events, including performances in February by the London Symphony Orchestra and Warsaw Philharmonic Orchestra, two orchestras closely associated with the composer. The City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra, where Panufnik was principal conductor from 1957 to 1959, will perform a special concert on his birthday, Sept. 24. His daughter, Roxana, an acclaimed composer herself, will attend. And London’s Kings Place concert hall has dedicated Nov. 30 to Panufnik. More than two decades after his death, Panufnik remains well-remembered.

Chicago-based writer Jack Zimmerman has authored a couple of novels, countless newspaper columns and was the 2012 recipient of the Helen Coburn Meier and Tim Meier Arts Achievement Award.

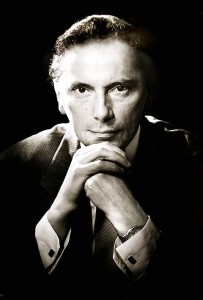

PHOTO: Detail from an oil portrait of Sir Andrzej Panufnik.