In his first eight years out of music school, Christopher Martin had already enjoyed a privileged career. The gifted young trumpeter played for four years in the Philadelphia Orchestra, one of the country’s most esteemed ensembles, and then he took over in 2001 as leader of the trumpet section for the Atlanta Symphony Orchestra, where he admits he could have remained happily until retirement.

But all along, he had his sights on what was for him a more vaunted ensemble – the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. One of his earliest musical memories is hearing the ensemble’s 1980 recording of Mussorgsky’s Pictures at an Exhibition with then-music director Georg Solti. Being part of the CSO became a dream that Martin couldn’t shake off.

“Not to be too biased, it’s really the best orchestra in this country,” Martin said. “In terms of brass tradition, it has been for so long the gold standard, because of my predecessor and everyone in the brass section’s mentor, Adolph [“Bud”] Herseth. So because of that, it has an enormous allure for any brass player, especially any trumpet player, to be part of that tradition, to be part of that sound.”

In 2005, after striking out during two earlier auditions, Martin was appointed the CSO’s principal trumpeter by then-music director Daniel Barenboim, and he has been an important presence in the orchestra since. Audiences will have a chance to get an up-close look at his artistry when he takes centerstage as soloist Oct. 2-4 during the orchestra’s first-ever performances of 20th-century Polish composer Andrzej Panufnik’s Concerto in modo antico (Concerto in an Ancient Style).

A native of Marietta, Ga., a suburb of Atlanta, Martin, 39, is the son of musical parents. His mother sings in the Atlanta Symphony Chorus, and his father serves as a school band director and is an amateur French horn player. At age 9, he began taking French horn lessons from his father, but within a few weeks, he realized that the instrument did not suit him, so he switched to the trumpet. “It didn’t feel right to me,” he said of the French horn. “It didn’t sound right to me. And the trumpet, sonically, was more appealing, because I was a quiet kid, kind of shy, and the trumpet was anything but that. So the fact it was so different from what I was used to, sort outside of my box, that’s what really attracted me to it.”

Martin’s early instruction on the trumpet came from his father, who later guided him to other teachers, including Larry Black, who retired from the Atlanta Symphony in 2003 after a 33-year career. Martin went on to earn his bachelor’s degree in 1997 from the prestigious Eastman School of Music in Rochester, N.Y., where his main teachers were Charles Geyer and Barbara Butler.

Even after playing in two other major orchestras, Martin realized it was still a significant adjustment moving to the Chicago Symphony, starting with the expanded workload — something he revels in. “We play a lot of concerts here and we play a lot of concerts here with terrific and demanding brass parts and trumpet parts,” he said. “That’s another thing that greatly appeals to me about being here is that you really have a chance to be tested in a musical way but [you] also find great inspiration and motivation musically on a weekly basis.”

Even more important, he said, is the sense of responsibility that comes with upholding not only the CSO’s superior standards in general but especially in preserving the celebrated sound of its brass section. He describes that sound, which he attributes in significant measure to Herseth, the Chicago Symphony’s influential principal trumpeter from 1948 through 2001, as “brilliant, articulate, pointed and clear” but also lyrical when necessary.

“But I think the most important thing is that there is a sense of adventure,” Martin said. “There is an attitude of risk-taking in the brass section. We’re trying to go for the big moment, and we’re trying to make that moment bigger than it was the last time and bigger than it was yesterday and better than it was at the last concert. That attitude is the most important thing.”

The CSO’s trumpeters play different instruments depending on the repertoire. Most often, they can be heard on instruments by Yamaha or Vincent Bach, a well-regarded American brand manufactured by Conn-Selmer Inc. But in historical Austro-Germanic works, such as Beethoven’s Symphony No. 9, which will open the CSO season on Sept. 18, the trumpeters switch to instruments made by Schagerl, a family-owned company in Austria. Martin’s practice room at home has an array of 12 trumpets in different sizes and keys, and when he is not preparing for an upcoming concert, he loves tinkering with mouthpieces or experimenting with a new technique. Adding even more variety, Martin will perform on a piccolo trumpet — a smaller instrument pitched an octave above a normal trumpet — for a Nov. 20-25 series of concerts featuring J.S. Bach’s Brandenburg Concertos. Martin’s piccolo trumpet was produced by Schilke Music Products, which has a fabrication plant in Melrose Park.

Although Martin played under Barenboim for only one year, he still has strong memories of his tenure, praising the sense of freedom that came with his conducting and the variances in performances of the same work from one concert to next. “We all had the sheet music in front of us and it was rehearsed,” he said, “but there was a sense at each concert that there was a real improvisation, that he [Barenboim] didn’t know how the piece would flow for him that night until he got to the moment, so by extension, neither did we. So there was a real sense of the orchestra, being on edge, not necessarily in a negative way, but on edge, paying close attention and with a high focus on what he was doing, because you really didn’t know what was going to happen. It made for some scary times, of course, but it made for some really incredible musical moments.”

With Riccardo Muti, who became the CSO’s music director in 2010, there is less of an improvisatory feel, Martin said, because he is so well-studied and knows every of inch a score so well that can he sing virtually any part in rehearsal. “He has well thought out every bar from start to finish, and our work with him tends to be meticulous and intense, so our concerts are the same,” Martin said. “Our concerts are highly focused and highly charged with mental energy, as they were with Barenboim but in a very different way. I find with Muti, there’s a sense that concert after concert, night after night, we’re sort of clawing our way to this perfect, 100-percent interpretation, not in terms notes or technical perfection, but in terms of the concert experience.”

Although Martin thrives on his week-to-week playing with the orchestra, he also delights every other season or so in having the opportunity to perform as a soloist. In 2012, he was spotlighted in the world premiere of American composer Christopher Rouse’s concerto, Heimdall’s Trumpet, which the CSO commissioned for Martin.

“In some ways, it’s the most fun, because you are as free as you can be in this classical world,” Martin said. “All of our normal jobs in the CSO are to be part of a big machine and to make it work. We all have our own ideas, and we all have our own sense of direction, but we’re constantly shifting and adjusting and molding that to what works best for the group and what works best for the whole institution. When you’re playing a concerto, you have a lot more freedom. The conductor can’t really tell you what to do for the most part, and it is nice to shape your own phrasing, it’s nice to choose your own adventure in the piece and just go for it.”

Martin has played most of the main trumpet concertos during his career, but Muti took him completely by surprise when the conductor asked if he would be interested in taking the solo role in Panufnik’s Concerto in modo antico (1951, revised 1955). It will open a program that also features Tchaikovsky’s Symphony No. 3 (Polish). The trumpeter admits that had never heard of the obscure 15-minute work, and he checked with many of his colleagues, and only one of them knew of it. “It’s not like any piece I’ve ever played before, I have to say,” he said. “I’m happy to have learned it and happy the Maestro suggested it, because I truly think I could have gone my entire career and not even known that it existed.”

The rare performances of the concerto are part of the worldwide celebration this year of the centennial of the famed Polish composer, who died in 1991. Panufnik helped revive classical music in Poland after World War II but was forced to flee communist oppression in 1954, settling in England, where he became a citizen in 1961. He refused to return to his homeland until 1990, when democracy was restored after the fall of the Soviet Union. The composer’s output encompasses 10 symphonies, including the Sinfonia Sacra (1963), which is his most frequently performed work, and the Symphony No. 10 (1988, revised 1990), which the CSO commissioned for its 100th anniversary.

The concerto, which consists of seven contrasting sections that are played without a break, has a kind of neo-Baroque feel. In his program notes for the work, Panufnik wrote that much early Polish music has been lost or forgotten, because of the many foreign invasions that have ravaged the nation. “In my Concerto in modo antico, I tried to fill this gap,” the composer wrote, “and make use of fragments of vocal and instrumental work by 16th– and 17th-century Polish composers, whose work I discovered during my research. I endeavored to re-create as near as possible the true period style, developing the themes rather than modernizing them by distortion.”

The biggest challenge in performing the work, Martin said, is doing justice to its striking, lyrical lines. “These are songs,” he said. “Sometimes the simplest music is the hardest, as we say, and sometimes the hardest thing to do is to play a simple phrase and play it well and play it musically and sing. The challenge really comes from that — finding the right sound, the right voice, the right phrasing for these lines.”

Kyle MacMillan, former classical music critic for the Denver Post, is a Chicago-based arts writer.

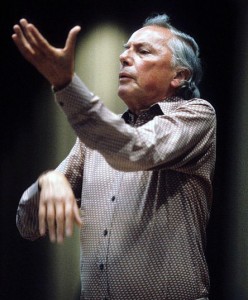

PHOTO: Christopher Martin, CSO principal trumpet, and guest conductor Jaap van Zweden perform Christopher Rouse’s Heimdall’s Trumpet at Symphony Center in December 2012. | Todd Rosenberg Photography