In the late ’90s, Lucasfilm began rolling out “Special Editions” of the first “Star Wars” trilogy: “Star Wars” (1977), “The Empire Strikes Back” (1980) and “Return of the Jedi” (1983). Along with digitally restoring the originals, improving special effects, adding new scenes and dialogue, and giving the films explanatory subtitles, the remastered films were released to theaters, where they became a box-office sensation once again. Though some fans decried the move as a marketing ploy for the upcoming prequels, the Special Editions brought the franchise back to the forefront of pop culture after more than a decade on the fringes. In his review of the 1997 version of “The Empire Strikes Back,” which the Chicago Symphony Orchestra will present in live-to-picture concerts Nov. 23-25, critic Roger Ebert called it “a visual extravaganza from beginning to end, one of the most visionary and inventive of all films.”

BY ROGER EBERT

The best of three “Star Wars” films, “The Empire Strikes Back” is also most thought-provoking. After the space opera cheerfulness of the original film, this one plunges into darkness and even despair, and surrenders more completely to the underlying mystery of the story. It is because of the emotions stirred in “Empire” that the entire series takes on a mythic quality that resonates back to the first and ahead to the third. This is the heart.

The film was made in 1980 with full knowledge that “Star Wars” had become the most successful movie of all time. If corners were cut in the first film’s budget, no cost was spared in this one: It is a visual extravaganza from beginning to end, one of the most visionary and inventive of all films.

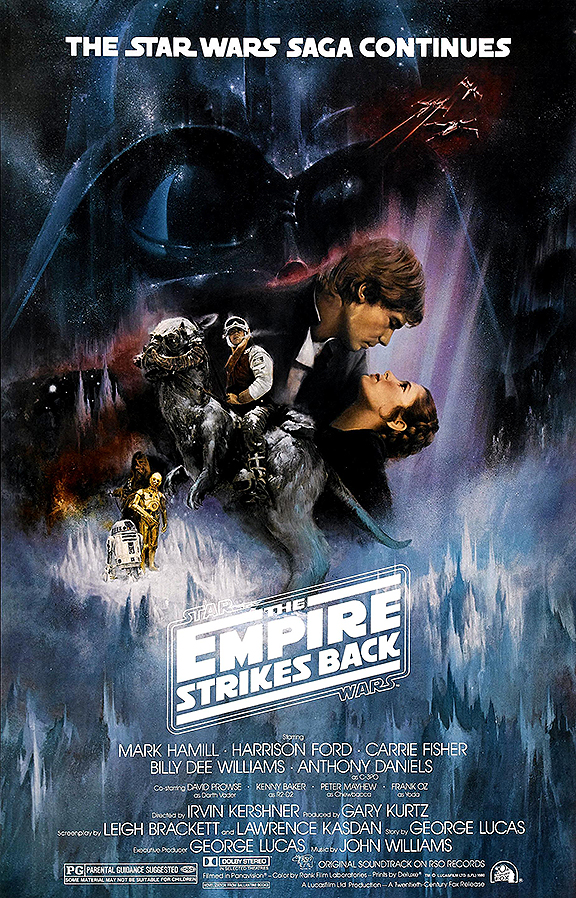

The poster for the original 1980 release of “The Empire Strikes Back.”

Entirely apart from the story and the plot, the film is worth seeing simply for its sights. Not for the scenes of space battle, which are more or less standard (there’s nothing here to match the hurtling chase through the high walls of the Death Star). But for such sights as the lumbering, elephantlike Imperial Walkers (was ever a weapon more impractical?). Or for the Cloud City, on its spire high in the sky. Or for the face of a creature named Yoda, whose expressions are as convincing as a human’s, and as subtle. Or for the vertiginous heights that Luke Skywalker dangles over, after nearly plunging to his death.

There is a generosity in the production design of “The Empire Strikes Back.” There are not only the amazing sights there before us, but plenty more in the corners of the screen, or everywhere the camera turns. The whole world of this story has been devised and constructed in such a way that we’re not particularly aware of sets or effects — there’s so much of this world that it all seems seamless. Consider, for example, an early scene where an Empire “probe droid” is fired upon on the ice planet Hoth. It explodes. We’ve seen that lots of time. But then hot pieces of it shower down on the snow in the foreground, in soft, wet plops. That’s the kind of detail George Lucas and his team live for.

There is another moment. Yoda has just sent Luke Skywalker into a dark part of the forest to confront his destiny. Luke says a brave farewell. There is a cut to R2-D2 whirling and beeping. And then a cut back to Yoda, whose face reflects a series of emotions: concern, sadness, a hint of pride. You know intellectually that Yoda is a creature made by Frank Oz in a Muppet shop. But Oz and Lucas were not content to make Yoda realistic. They wanted to make him a good actor, too. And they did; in his range of wisdom and emotion, Yoda may actually give the best performance in the movie.

The worst, I’m afraid, is Chewbacca’s. This character was thrown into the first film as window dressing, was never thought through, and as a result has been saddled with one facial expression and one mournful yelp. Much more could have been done. How can you be a space pilot and not be able to communicate in any meaningful way? Does Han Solo really understand Chew’s monotonous noises? Do they have long chats sometimes? Never mind.

The second movie’s story continues the saga set up in the first film. The Death Star has been destroyed, but Vader, of course, escaped and now commands the Empire forces in their ascendancy against the Rebels. Our heroes have a secret base on Hoth, but flee it after the Empire attack, and then the key characters split up for parallel stories. Luke and R2-D2 crash-land on the planet Dagobah, and Luke is tutored there by Yoda in the ways of the Jedi and the power of the Force. Princess Leia, Han Solo, Chewbacca and C-3PO evade Empire capture by hiding their ship in plain sight and then flee to the Cloud City, ruled by Lando (Billy Dee Williams), an old pal of Han’s and (we learn) the original owner of the Millennium Falcon, before an unlucky card game.

There are a couple of amusing subplots, one involving Han’s easily wounded male ego, another about Vader’s knack of issuing sudden and fatal demotions. Then comes the defining moment of the series. Can there be a person alive who does not know (read no further if you are that person) that Luke discovers Darth Vader is his father? But that is not the moment. It comes after their protracted (and somewhat disorganized) laser-sword fight, when Luke chooses to fall to his death rather than live to be the son of Vader.

He doesn’t die, of course (there is a third movie to be made); he’s saved by some sort of chute I still don’t understand, only to dangle beneath the Cloud City until his rescue, and a conclusion that only by sheer effort of will doesn’t have the words “To be continued” superimposed over it.

Perhaps because so much more time and money was spent on “The Empire Strikes Back” in the first place, not much has been changed in this restored and spruced-up rerelease. I do not recall the first film in exact detail, but learn from the “Star Wars” web pages that the look of the Cloud City has been extended and enhanced, and there is more of the Wampa ice creature than before. I have no doubt there are many improvements on the soundtrack, but I would have to be a dog to hear them.

In the glory days of science fiction, critics wrote about the “sense of wonder.” That’s what “The Empire Strikes Back” creates in us. Like a lot of traditional science fiction, it isn’t psychologically complex or even very interested in personalities (aside from some obvious character traits). That’s because the characters are not themselves — they are us. We are looking out through their eyes, instead of into them, as we would in more serious drama. We are on a quest, on a journey, on a mythological expedition. The story elements in the “Star Wars” trilogy are as deep and universal as storytelling itself. Watching these movies, we’re in a receptive state like that of a child — our eyes and ears are open, we’re paying attention, and we are amazed.

Reprinted with permission of the Ebert Co. Ltd.