The movie opens with the Paramount Pictures mountain centered on a backdrop of clouds rolling across the screen. The logo morphs into a real mountain. A shadow in a fedora walks up into the frame and faces the mountain. We don’t know who he is or what he’s doing. All we can see is his silhouette, but what we can hear tells us that we are in for an adventure.

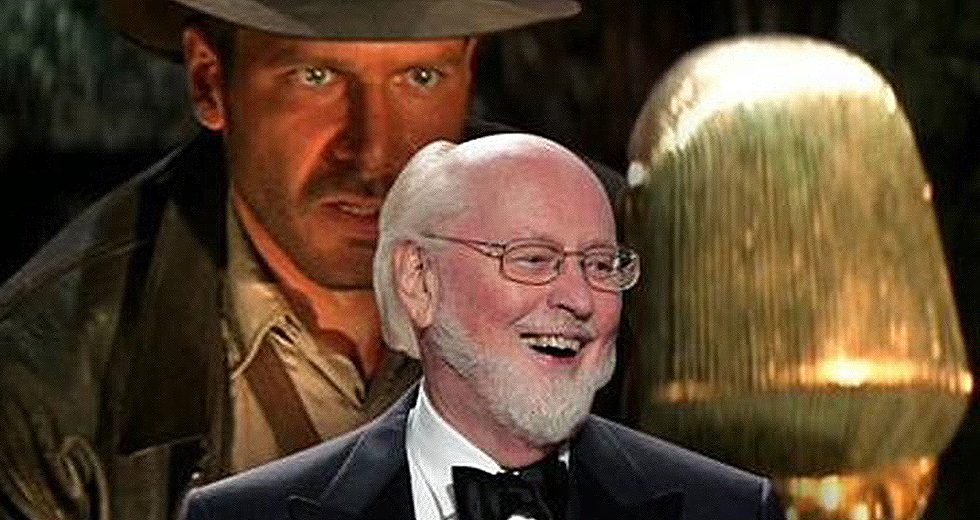

In 1981, that was our first glimpse of Indiana Jones, archeologist-superhero. This music, though, seemed familiar. The sweep of orchestral strings was driven with haunting horns, flowing flutes and punctuated by triumphal trumpets. We knew John Williams’ scores for “Jaws,” which captured the sound of a killer shark, and “Star Wars,” which took us to galaxies far, far away. But this music was taking us somewhere else.

Turning back the clock nearly 50 years, “Raiders of the Lost Ark” played homage to the old Hollywood serials with Allan Quatermain and Tarzan. It led to even more adventures with Indiana Jones in theaters, TV, books — and even concert halls — which will be the case in a live-to-picture concert Aug. 2 with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra at Ravinia.

Emilio Audissino, a researcher at the University of Southampton, wrote his master’s and doctoral theses about the film music of Williams and turned them into a fine book, John Williams’s Film Music, published in 2014.

He ticks off the names of classical film score composers (and conductors) who serve as role models for Williams: Alfred Newman (“The Grapes of Wrath”), Franz Waxman (“Sunset Boulevard”), Bernard Herrmann (“Vertigo” and “Psycho”) and Max Steiner (“Casablanca”).

Classical music influences often found in Williams’ scores include Richard Wagner (using leitmotif to identify a character) as well as Russian romantics Sergei Prokofiev and Dmitri Shostakovich. And it’s hard to think about Russian impressionists Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov and Igor Stravinsky when Williams summons everything from tam-tam to trombones to orchestrate the action fully.

As distinguishing features of the reimagined classical music style, Audissino lists:

• Leitmotif (recurring as the Indiana Jones march).

• “Mickey Mousing” (the old cartoon trick of syncing musical notes with screen action, as with whip cracks and the rearing back of menacing snakes).

• Thematic development (heard in the sweep of strings when Jones and his love interest, Marion, are together).

• Big orchestra (the London Symphony, which performed Williams’ score on the soundtrack).

• Late romantic dialect (taken to the extreme with classical clichés).

Williams covers them all in “Raiders of the Lost Ark.” About those clichés, he has been unapologetic. In the video documentary “The Music of Indiana Jones” by Laurent Bouzereau, included with the 2003 DVD box set “The Adventures of Indiana Jones,” Williams explains: “We have the Nazis, you know, and the orchestra hits these 1940s dramatic chords … seventh degree of the scale on the bottom, kind of an old signal of evildoer [the sadistic sweaty, bespectacled Major Toht]. We just unabashedly did that for the camp fun of it. It’s admissible in a style of a picture like this.”

With his parallel career as a conductor, Williams brings extra efforts in adapting concert suites from his film scores. “His particular care for concert versions is proved by the fact that he is the only composer whose numerous concert suites can easily be found for sale in authoritative full scores,” Audissino says.

A version of this article appeared previously on Sounds and Stories, when the CSO presented “Raiders of the Lost Ark” in 2016.