Steven Spielberg picked up the phone at his Universal Studios office. “You gotta get over here!” Martin Scorsese breathlessly told him. “This score is brilliant! You gotta drive over here!”

Spielberg immediately headed to Warner Bros. Studios, where Scorsese had been sitting in on the scoring session for his latest movie, “Taxi Driver.” “You gotta meet Bernard Herrmann,” Scorsese said. He grabbed Spielberg by the hand, raced him into the recording studio and parked him squarely before the great composer, who, even seated, projected an imposing figure, his large, protruding stomach showered with cigar ashes.

“Bennie, this is my friend Steven Spielberg,” Scorsese said.

“Oh, Mr. Herrmann!” Spielberg blurted out. “I’m such an admirer of your work. You’re such an amazing genius!”

Herrmann flashed one of his infamous scowls. Then he replied, “So why do you always hire John Williams?”

Herrmann could not have known how prescient his question would be: only four of Spielberg’s 34 feature films do not carry the credit “Music by John Williams.”

Two of the duo’s most cherished projects, “E.T., The Extra-Terrestrial” (1982) and “Raiders of the Lost Ark” (1981), will be shown at Ravinia this summer, with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra supplying Williams’ music live: “E.T.” on Aug. 1 and “Raiders” on Aug. 2. One of Herrmann’s most critically acclaimed scores, for Alfred Hitchcock’s classic “Vertigo” (1958), will be shown a few weeks later, on Aug. 15, with the CSO again bringing the score to life.

Despite their fateful meeting in December 1975, Spielberg and Herrmann would never work together. Herrmann, the creator of the music for “Citizen Kane” (1941), “The Day the Earth Stood Still” (1951) and “North by Northwest” (1959), died of a heart attack in his sleep, only hours after glaring at the young director of the blockbuster movie “Jaws” (1974).

In a sense, their meeting earlier that day marked a metaphorical passing of the baton from cinema’s greatest composer/director team to that of the next generation, and an arguably even greater team at that.

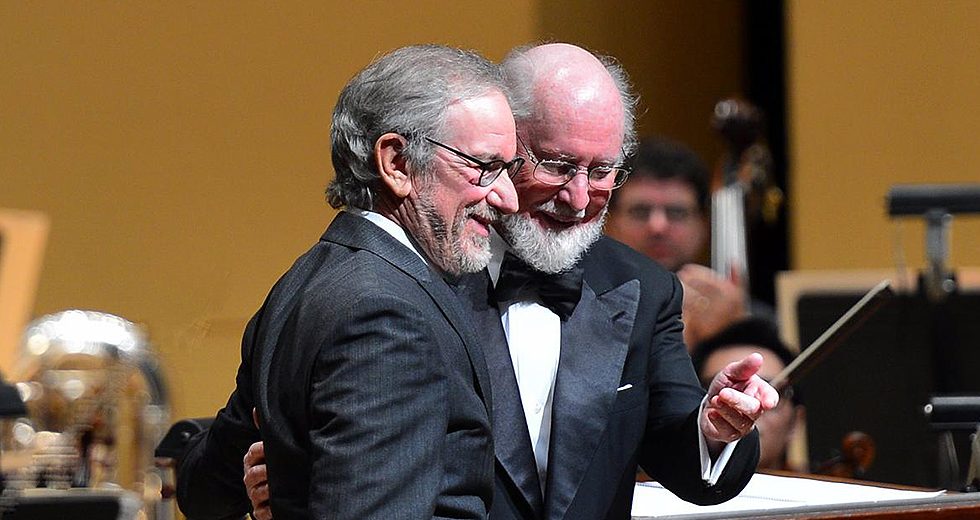

Until their bitter falling out over the political thriller “Torn Curtain” (1966), Herrmann and Hitchcock had made a magical marriage of music and moving images. Their relationship — the clash of titanic egos — sharply contrasted with how Spielberg and Williams have worked together for 44 years. “He’s never once said, ‘I don’t like that.’ Or ‘this won’t work.’ Or ‘we need to do something else,’ ” Williams said of Spielberg. “He’s enjoyed everything I’ve done, as I have with him.”

“I have absolute trust and faith that John is right when he sees my movie for the first time,” Spielberg said. “He enhances it and takes it to an entirely different level.”

So, what secret did Williams/Spielberg possess that enabled them to outlast and outperform Herrmann/Hitchcock?

In a word: style.

Herrmann supplied a defined musical style to Hitchcock’s films, and the composer’s unwillingness or inability to adapt eventually eroded his relationship with the director.

“John is different,” Spielberg said of his musical sidekick. “John doesn’t have a style like Dimitri Tiomkin has a style. I can close my eyes and recognize a Dimitri Tiomkin score. John is much more a chameleon. He changes his style to suit the picture that we’ve made. That’s the most amazing thing about working with John. I don’t get the same John Williams twice.

“Unless it’s a sequel.”

This is an excerpt of an article published in the Ravinia magazine; to read the complete version, click here.

Dann Gire, the longtime film critic of the Daily Herald, is the president and founding director of the Chicago Film Critics Association.