While the term “neo-classical” serves as highly useful shorthand for describing much of Igor Stravinsky’s output, he himself hated the term. It meant “absolutely nothing” to him, even as he spent more than 30 years working with the forms and patterns of earlier musical styles.

It’s ironic, considering that the borders surrounding his neo-classical period are so well-defined. In 1919, he was still deeply buried in his Russian period, writing, among other works, the “Four Russian Songs” and the second concert suite taken from The Firebird. Only a year later his nationalism had given way to an entirely new direction, demarcated by a single piece: Pulcinella. (The Chicago Symphony Orchestra, under guest conductor Cristian Macelaru, will perform the Suite from Pulcinella, along with other Stravinsky works, in a program Feb. 20-25, curated by Pierre Boulez. Under Boulez, the CSO also recorded Pulcinella for a CSO Resound release in 2010.)

By comparison, the time-shift from Beethoven’s “early” to his “middle” period is so extensive that a separate “transitional period” had to be conjured. The year 1800 is generally cited as the dividing line, but it is at best an approximation, with a spectrum of audacious transitional works produced over several years. The Kreutzer sonata (1803) functions as a terminal work of this transitional period, which also includes the Moonlight and Tempest sonatas. In short, a gradual evolution not an abrupt change.

Not so with Stravinsky and Pulcinella. In 1919, the composer was prompted by Diaghilev to write a ballet based on unfinished sketches by Giovanni Pergolesi (though many of these works were later to be discovered to be from contemporaries of Pergolesi), and in these manuscripts, Stravinsky found a creative direction that was to drive him forward for decades. The radical bomb-throwing modernism was gone. In its place, a respectful, modest — albeit personal and characteristic — nod to the virtues of the Baroque. From human sacrifice to commedia dell’arte in just seven years.

“Pulcinella was my discovery of the past,” he said, “the epiphany through which the whole of my late work became possible. It was a backward look, of course — the first of many love affairs in that direction — but it was a look in the mirror, too.”

His “new” approach — restating older textures and forms in his own accent — was more than just a source of individual creative inspiration. It paved the way for numerous composers, playing a central role in the development of 20th century music. Milhaud, Poulenc, Martinu, Kodaly and Bartok all found fertile ground in this direction. As with The Rite of Spring, Stravinsky had once again forged a path that would be heavily trod by others, and he paid a cost for this transition as well. Earlier derided for his modernism, he was now derided for abandoning it. Everyone’s a critic.

As abruptly as it started, Stravinsky’s neo-classic period came to a close. Inspired by engravings by the 17th-century artist William Hogarth, Stravinsky composed the opera The Rake’s Progress in 1951, paying musical homage to Hogarth’s era. In Europe that year, for the Rake’s premiere, he found himself exposed to the music of Anton Webern, and the wheel turned again. Immersed in Webern’s works, he charted a new direction for himself, serialism. The critical chorus was predictable. Those who had committed themselves to the neo-classic thread of modern composition, in opposition to the Schoenbergian thread, felt a sense of personal betrayal by their standard bearer. But, as with his shift to the neo-classical style, Stravinsky didn’t look back. The rest of his career was spent composing in this vein — and waiting for the rest of the world to catch up.

Peter Lefevre, based in California, writes about music for the Orange County Register and Opera News.

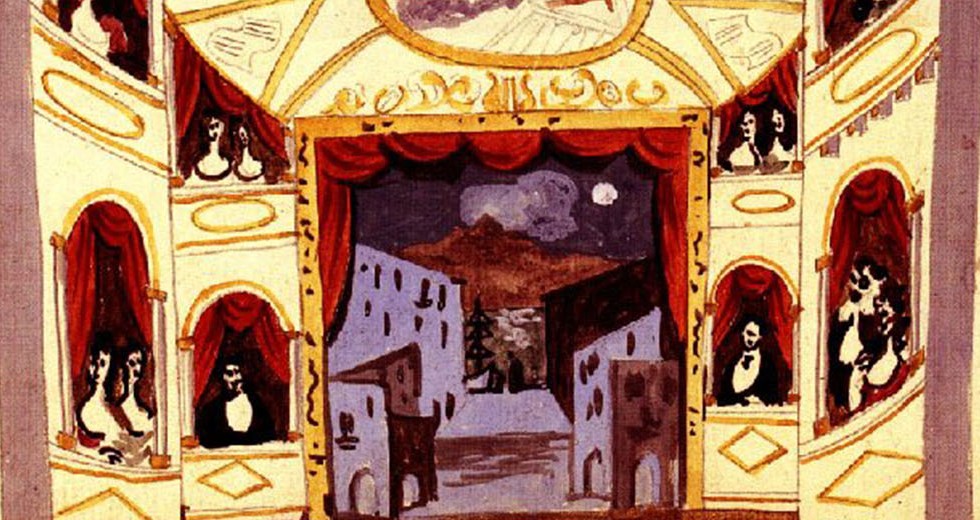

ABOVE: A Pablo Picasso drawing for the original 1920 production of Pulcinella at the Paris Opera Ballet.