Sometimes the stars — the human type as well as the celestial — actually do align.

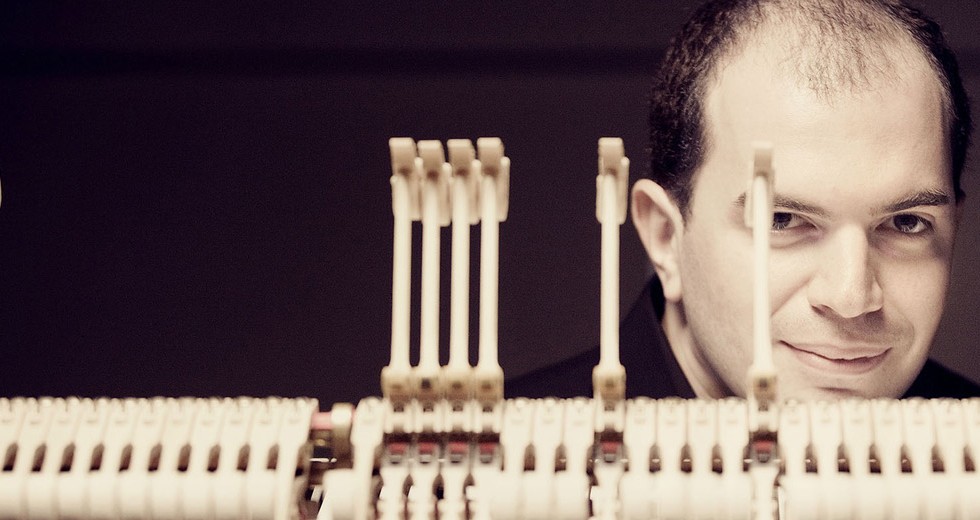

Winner of the 2010 Gilmore Artist Award, the Russian-born Kirill Gerstein is one of the most fascinating pianists on the scene today. Born in 1979, he grew up in the former Soviet Union and was equally interested in jazz and classical music. He came to the United States in 1993 as a teenager to attend a summer jazz course at the Berklee School of Music in Boston and decided to stay in the States. Soon, however, he shifted his focus exclusively to classical music. In 2006, when he met conductor Semyon Bychkov, Gerstein was a young pianist just starting to make an international career. A generation older and already an established conductor, Bychkov helped his career along, and they became good friends.

For three concerts Oct. 24-26 with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, Gerstein joined his longtime colleague as the soloist in Prokofiev’s virtuosic Piano Concerto No. 2.

The two Russians first met in Birmingham, England. Gerstein was one of four pianists appearing in a concert of Stravinsky’s monumental folk cantata, Les Noces, with the Birmingham Contemporary Music Group, led by British conductor Thomas Ades. The other pianists were a stellar trio: Jean-Yves Thibaudet and the Labeque sisters, duo pianists Katia and Marielle. Bychkov, Marielle’s husband, was simply along for the ride.

“After the concert, we started talking,” Gerstein said. “It was one of these occasions where immediately the conversation seemed to flow and go in all sorts of interesting directions. He said, ‘I’d like to hear you play something solo. Why don’t you send me a recording?’ That’s very, very nice, but as a young soloist, often when you send the recording, nothing happens.

“Well, I sent the recording and Semyon replied a couple of weeks later. He said, ‘I really like what you do, but it will take some time because my planning is so far into the future.’ But maybe a month or so later, there came an invitation to play the Shostakovich Second Piano Concerto in Munich.”

“Well, I sent the recording and Semyon replied a couple of weeks later. He said, ‘I really like what you do, but it will take some time because my planning is so far into the future.’ But maybe a month or so later, there came an invitation to play the Shostakovich Second Piano Concerto in Munich.”

Never mind that Gerstein hadn’t played that particular concerto in public. The young pianist suggested some alternatives, but Bychkov firmly but kindly insisted that the issue was not negotiable. “There came the dearest letter from Semyon,” Gerstein recalled. “It said, ‘I know that you haven’t played Shostakovich Second before, but unfortunately this is what the concert needs. I can tell you that I also have not done Shostakovich Second. I know that first times require some extra sweating, but I invite you to sweat together with me for the first time in Munich.’ ”

More than a decade before, Gerstein, then 14, had done some heavy sweating while trying to decide whether to make his career in jazz or in classical music. He didn’t think he could excel at both.

“It was a difficult decision because at the time I really had the possibility to go in either direction,” he said. “But I felt that [I had] to try to do it justice, which is always futile in the arts. You never manage to do anything justice, but one tries to give it one’s best. To give it my best, I felt I had to concentrate on one or the other. You can spend an entire day developing ideas for improvising. But to come to terms with at least some portion of the great repertoire of classical music, to master the instrument, takes more than the time that is allotted.”

Gerstein choose classical music rather than jazz. “I felt that, given the layers of complexity, to spend my days roaming the creations of Prokofiev, Rachmaninov or Beethoven and Brahms and Bach, to dedicate myself to this amazing repertoire would be, in the long term, more interesting than the joy of on-the-spot music making.”

In 2010 Gerstein won a kind of musical lottery, a contest he didn’t even know he had entered. In 1989, the estate of Irving S. Gilmore, a Kalamazoo, Mich., retail magnate, established an entirely different kind of piano competition. Modeling itself on the Chicago-based MacArthur Foundation’s genius grants, the Gilmore Foundation gives a $300,000 award every four years to a single pianist. The foundation makes the decision without the usual trappings of public elimination rounds, semi-finals and finals. Gilmore judges ask classical music insiders around the world to submit names of promising talent. Gilmore representatives then travel incognito to concerts over several years. They see pianists in their native habitat rather than in the artificial hothouse of a public competition. Recent winners have included Piotr Anderszewski, Leif Ove Andsnes and Ingrid Fliter.

Gerstein had been in the Gilmore’s sights for nearly a decade before winning the award. Named a Young Gilmore Artist in 2002, he became the first Young Artist to go on to win the top prize.

“I first heard about Kirill at Tanglewood,” said Dan Gustin, director of the Gilmore International Keyboard Festival since 2000. Previously, Gustin had been manager of the Tanglewood Festival for 15 years. “We didn’t really meet, but I had heard about him.”

Over the next decade, Gilmore staff tracked Gerstein’s thoughtfully created, technically polished performances. “The award can be given to anybody,” Gustin said. “There’s no age restriction, no nationality restriction. We’re looking for promise, for somebody with considerable musicianship. Not just technique — every 13-year-old kid these days has technique. Not pianism, but musicianship in the broadest sense, and also what we sensed as Kirill’s potential for growth. We got the sense that he was determined to make a career, that he had what it takes.”

Gerstein has used his award money to commission works from composers ranging from jazz master Chick Corea to Oliver Knussen. Now well established in his career, he is once again exploring the world of jazz, looking for points of contact between classical music and jazz.

In the spring, for its Truth to Power festival, the CSO will feature music by Prokofiev. After leaving Russia following the 1917 Revolution, Prokofiev tried living in the United States and Europe before finally returning to Russia in 1936. He wrote some major works there, including the ballet Romeo and Juliet. But he also ran afoul of Stalin’s insistence that Soviet composers write in a conservative, immediately accessible style.

Gerstein seems some hits of future unhappiness in his early piano concerto. “The Second Concerto is one of the most challenging and demanding monuments in the concerto repertoire, like the Rachmaninov Third, the Brahms Second and Bartok Second,” he said. “He writes with incredible ambition, and he actually succeeds.”

The scale of Prokofiev’s ambition is apparent in his diaries, Gerstein believes. Throughout his life, Prokofiev felt the need to prove himself, to outdo his competitors. “He’s writing incredible music but things were always uneasy going for him,” Gerstein said. “He’s in the conservatory, and he looks up with some jealousy at the more senior Rachmaninov and Stravinsky. He goes to Paris and there’s Stravinsky, who has done all this stuff with Diaghilev, and he tries to compete with that. Then he goes to America, and there’s Rachmaninov. Then he goes back to the Soviet Union, which was in some ways a tragic decision, and Shostakovich is there. He always felt that he was looking over his shoulder, that there was always someone who was doing better or [had it] easier.”

The Second Concerto hints at that pattern of inspired achievement and discontent. “The piece has a dark background, a lot of dark clouds,” Gerstein said. “But actually there’s a lot of humor and sarcasm in it. It’s not necessarily a dark piece, but it takes place in someplace where the weather is quite stormy and gloomy.”

Wynne Delacoma, formerly the classical music critic for the Chicago Sun-Times, is a freelance writer and reviewer.

PHOTOS: Kirill Gerstein (top) and Semyon Bychkov (inset).