Sir Georg Solti’s London study

As her vision diminished, and Chicago Symphony Orchestra violinist Alison Dalton struggled to read scores, she asked Lady Valerie Solti for advice.

A year later, now starting her 29th season with the CSO, Dalton recalls the confidences shared in Sir Georg Solti’s London study last September. “I told [Lady Solti] about my predicament — that my eyesight had failed me.

“She looked at the ceiling for about 15 seconds, and then looked straight at me — straight in the eye — and said, ‘Alison, you’ve had a good run.’”

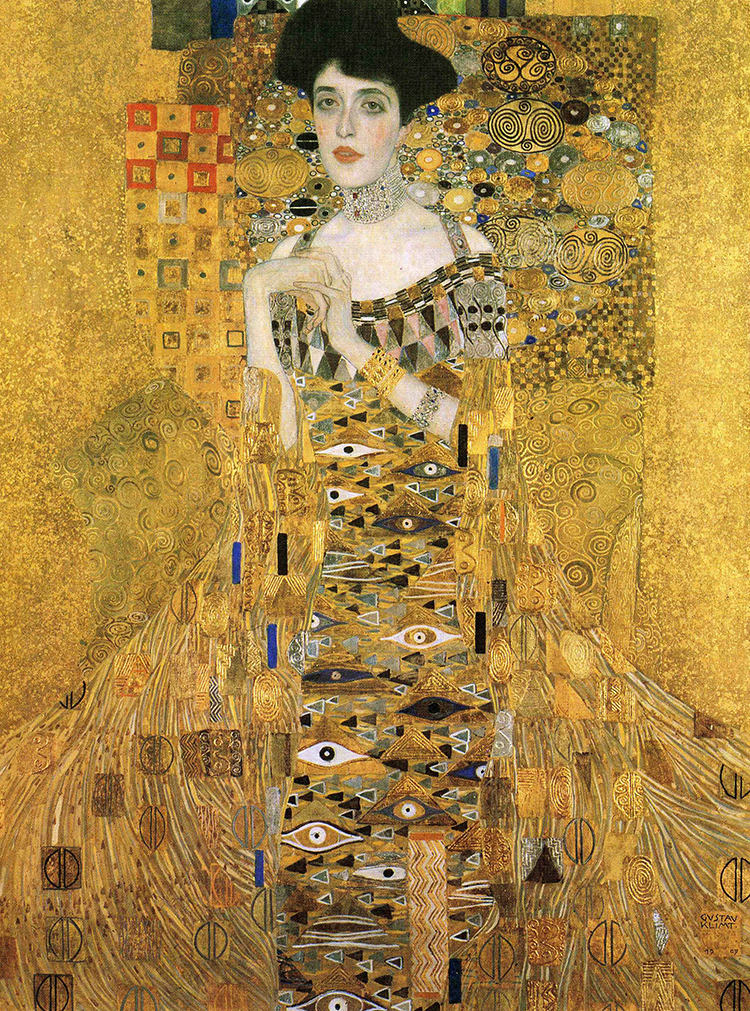

Gustav Klimt’s 1907 portrait of Viennese scion Adele Bloch-Bauer dissolves into a bright, twisting spectrum of spirals and flashes, while for Dalton, perception fades into a white, swirling center of diminished detail.

Lady Solti represents the vibrant legacy of Sir Georg, her late husband, the Hungarian music director who invited a young American violinist to join his Chicago ensemble in 1987. It was a curious if natural fit. Dalton, already an accomplished veteran of the Austrian (now Vienna) Radio Symphony Orchestra, thrived under the conductor’s authority, precision and respect for tradition.

With her chiseled visage and tall, stately bearing, Dalton looks the part, evoking Viennese scion Adele Bloch-Bauer, celebrated in Gustav Klimt’s 1907 portrait that defines Jugendstil painting, with its respect for craft and grasp at a new vitality.

Klimt’s Bloch-Bauer — her face in sharp, pale focus — dissolves into a bright, twisting spectrum of spirals and flashes, the periphery a golden blur. But as violinist Dalton’s vision descends, her perceptive world is Klimt’s opposite — strength discerning the peripheral palette, but a white, swirling center where detail diminishes. Notes, staffs, signatures — scores can twist beyond her acuity.

“My focal point is gone, and wherever I look, there’s the whiteout,” says Dalton, describing the permanent visual condition known as bull’s-eye maculopathy, which precipitated her CSO medical leave in 2013. “I’m having to use eccentric peripheral vision to see the music.”

Dalton knows that “historically people just have to quit. That’s old school, and I’m from that old school.”

But quitting’s not a present option.

Instead the violinist shifts her view, evolving a personal Jugendstil — a young style of thinking — that respects, she says, her “ability to remain relevant and to make the changes necessary” and lets her grasp the vital drive “to continue, to go forward.”

Professor Joy Bergelson’s Michigan lab

University of Chicago professor Joy Bergelson, outside her lab at the Warren Woods Ecological Field Station in Michigan, says of her friend, CSO violinist Alison Dalton: “I love music and I just want her to succeed and be happy.” | Photo: Andrew Huckman

The University of Chicago’s innovative Warren Woods Ecological Field Station — professor Joy Bergelson’s new laboratory — is shrouded in Michigan forest that, on this sunny summer afternoon, might evoke for Dalton the perceptive whirls of Vincent van Gogh’s painted Provencal landscapes. Maize blossoms shimmer against tall, swept arbors and a swift, breezy azure sky. The violinist, assembling a rustic, colorful bouquet, is better with bright panoramas and strong contrasts than the details within. “I can see all the colors,” she tells me. “It’s when I look at you that I can’t see much. I can’t see your nose and your eyes.”

In Ray Bans and Chuck Taylors, a relaxed Dalton strolls the wildflowers, denim brushing against golden petals; she’s easygoing and serene, distant from Bloch-Bauer’s Viennese strictures.

Professor Bergelson, sporting matching sunglasses, sneakers and burnished highlights, says little, befitting an evolutionary biologist and U. of C. department chair whose observations usually come with titles like “Cheating, trade-offs and the evolution of aggressiveness in a natural pathogen population” (which is another way of saying that progressing pathologies deserve new and creative exploration).

Bergelson’s also a fledgling violinist who recognizes in Dalton “this old guard of people who just really love and appreciate the music — and I’m stupid about music, but I love music and I just want her to succeed and be happy.”

When the two met, the CSO violinist “was getting bounced around by the medical system, because she had eluded diagnosis, which gave me a challenge,” Bergelson recalls. “No, we cannot accept that kind of answer … because we just can’t. It makes no sense.

“She had a right to her life and a right to her career.”

Bergelson channeled the tenacity that shaped her Warren Woods field station — the first U.S. lab based on ecologically sound passive-house technology (“I didn’t understand anything about passive buildings at the beginning. I understand a reasonable amount now,” she demurs) — into developing dynamic visual accommodations for Dalton. Those measures, like the ground-breaking facility, reflect “an ever-rising standard and an inability to give up.”

Best Buy after-hours

Dalton, ever the musical traditionalist, thrives on “the native, relic page,” scores that preserve “the erudition of the original copyist, and all the information that’s come down through time in those parts,” including comments that violinists write in the margins. Once she even scribbled down Maestro Solti’s remark “Das ist mir wurst,” something akin to “It’s all sausage to me.”

As Dalton considered and reconsidered solutions that would magnify and preserve her native scores and pages, Bergelson the evolutionary biologist helped concoct a technological sausage that’s a mashed-up, mutated mix of touchscreen, USB and Wi-Fi, dashed with a quick kick of garlic salt.

Bergelson favored an easy-to-use digital display that enlarged CSO scores to readable levels. Dalton wanted something “100 percent invisible” to colleagues and audiences alike — “a perfect crime scene leav[ing] no clue as to how it’s been perpetrated.” The violinist established her own high standard — she wouldn’t “topple or shake the solidity of the organization, or the performance, or the music in any way.”

Shaking Best Buy salespeople was another matter altogether. The professor encouraged the violinist to experiment with several screen sizes, so Dalton headed to superstores armed with flash drives, masking tape and a 1707 Milanese Grancino. She moved from display to display, uploading scores and taping off tall/wide aspect ratios, then letting fly on her violin.

Dalton would arrive with husband Charles Barker, a globe-trotting, gadget-versed attorney, “just before the store closed, so I’d disrupt as few people as possible, and we’d display the music on the different-size monitors to see at what magnification I could feel comfortable.” They heard sales pitches like “‘You can get the music this big!’” and compliments from puzzled customers: “‘Wow — you’re awesome! Do you play in a band?’” Her impromptu audience, Dalton remembers, “sat down and leaned back in the [store’s] vibrating chairs and listened for a little while. I think I was using the [Olivier] Messiaen Turangalîla first-violin part because it’s so damn difficult, and I wanted to put myself really to the test.”

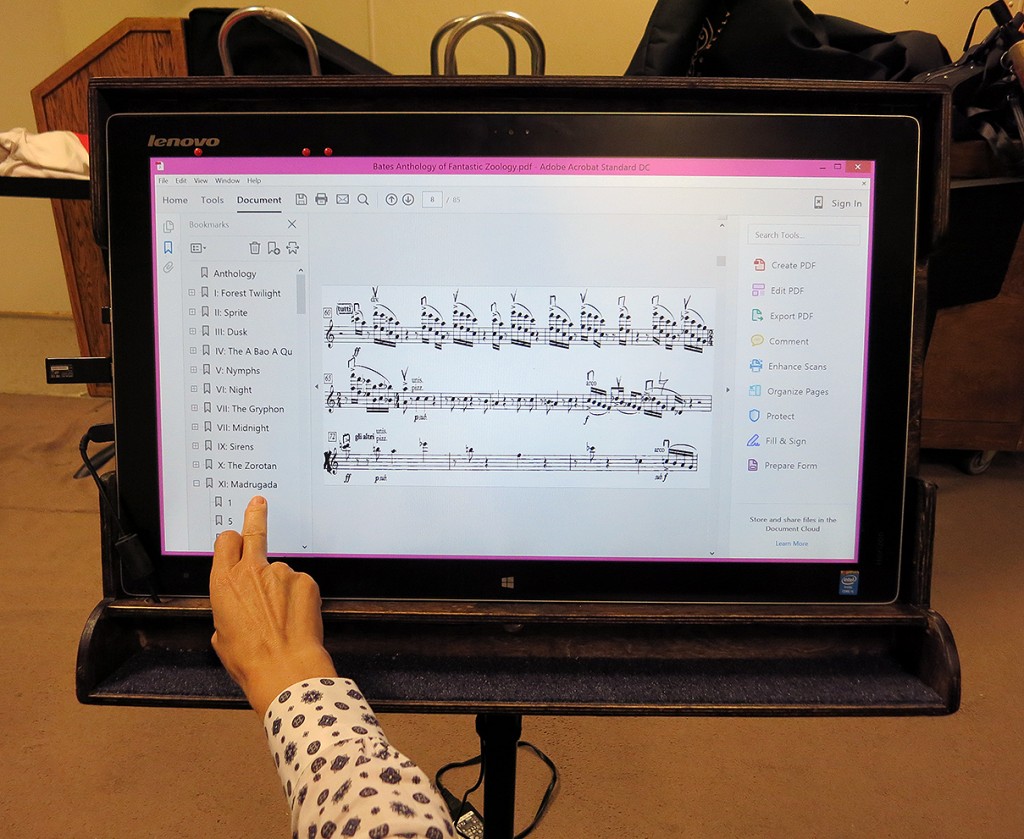

Dalton and company settled on a 27-inch, battery-capable Lenovo touchscreen with a 16:9 aspect ratio. Essentially a long, large iPad, it’s the meaty heft in Dalton’s high-tech sausage.

She calls her score processor a “‘Fascinoter’ — I can not take my eyes off this thing.” The monitor shows three lines of music (versus 12 in printed scores) — the minimum Dalton needs to look ahead — at 400 percent magnification, enlarging sixteenth notes that challenge her most. She presses a foot pedal, rather than swipes, to reach the next set of measures.

Getting the vivid display out of the showroom and fit for Orchestra Hall meant adhering to Dalton’s self-imposed “100 percent invisible” standard. CSO stagehands set to work on custom housing that would evoke the look and feel of conventional music stands. Like a giant iPad cover, interior tabs lift the system away from the casing and holes correspond with the tablet’s vents, reducing the possibility of overheating. Audiences on Orchestra Hall’s front-facing main floor and balconies scarcely notice the addition.

Dalton worried the glowing display might distract terrace patrons behind the musicians; the screen’s auto-brightness sensors would run wild in low lighting. Husband Barker solved the problem by appending a clip-on reading light; Dalton shines it at the tablet’s sensor to fool the screen. (Fixes like yellow plastic to trick Ravinia mosquitos might be in the offing.)

She shows off a coarse mix of redundant accessories that would stymie Noah. “I have two keyboards in case I can’t get my touchscreen to work. I have my two Bluetooth pedals. I have my two USB pedals. I have two pair of glasses.” Two lights, some dongles, extra cords — Dalton’s missing a key component. “Where is the violin, anyway?”

That’s not all. “We’ve got the bag of makeup, too. You could have a wardrobe malfunction.”

Even Dalton’s wardrobe accessories become technology accessories. For concerts, she uses a black knee-high sock to camouflage a bottle of McCormick’s garlic salt — her casing on the sausage, so to speak. (Shouldn’t a Solti loyalist choose paprika?) “The diameter of this tube is perfect for the arch of my foot, and it supports my ankle.”

Or to paraphrase Cole Porter, in modern days a glimpse of stocking hides spices the fiddler’s rocking. As Dalton pedals between measures dozens of times during a concert, her left ankle tends to grow sore. The still-filled savory cylinder — a risky ingredient in Dalton’s high-tech wurst — provides low-tech allium-sodium power for her up/down pivots.

Dalton hides the pedal, wired to her display’s USB port, beneath a blond cloth that matches Orchestra Hall’s parquet stage. She nixed the use of a Bluetooth pedal after the Blackhawks recent championship run. Bluetooth is a wireless standard, common in cellphones, for connecting or “pairing” different devices (Dalton’s pedal and display, for instance). During Game 3 of the Stanley Cup, CSO hockey fans were using their mobiles to check the pre-concert score, which flooded Dalton’s display with paring requests.

Even now, Dalton’s bemusement still shows: “There was no way that I could stop the Bluetooth people from coming in and out of the house. If that icon is jumping around because it’s being refilled with 23 and then 49 and then 16 Bluetooth icons as they come and go from the audience? I couldn’t find my serial number to pair.”

The Hawks’ triumph was Dalton’s loss. “We can’t use Bluetooth. It was cool, but it was too cool.”

Great America, on a thrill ride thanks to Mason Bates

The “native, relic page” Dalton sees on her screen — and what she wants most to see on her screen — is the score she’s always known. So violinist and professor opted for a passive system without what might be called “text recognition” — Dalton gets an exact snapshot of the score, enlarged, without the software recoding musical notes or registering dynamic markings. (They considered and rejected an active system that recognized and “bubbled” notes as the music advanced, loosely akin to composer and frequent CSO guest conductor Esa-Pekka Salonen’s iPad app, seen in last year’s Apple commercial.)

Bergelson uses words like “concatenate” to describe stringing together a host of Acrobat “.pdf” files into Dalton’s digitized score, which is the longest, toughest PowerPoint presentation you’ll ever view. Both women count on a crack squad of home-grown acolytes to digitally assemble the concert season. CSO music librarians scan weeks of repertoire from bound scores, then the violinist’s salaried “copyists” — Dalton’s son, Graham Woolley, a horn player, and cellist Allie Kreitman, Bergelson’s daughter — parcel the measures into three-line sequences enlarged for display on the tablet.

Dalton points out last-minute changes to the score of Mason Bates’ Anthology of Fantastic Zoology. | Photo: Andrew Huckman

Everyone aced an early test for any violinist, horn, cellist or evolutionary biologist, as they quickly corralled a changing musical menagerie of forest zoology. In June, Dalton’s second CSO concert back featured the world premiere of then composer-in-residence Mason Bates’ Anthology of Fantastic Zoology. Wednesday morning before the Thursday night concert, composer Bates opted for revisions to his “Madrugada” finale, where, he writes, “all of the animals fuse together in the darkest, deepest part of the forest.”

You’d expect the laptop-savvy composer, watching the morning rehearsal, might tweet or email his changes to the tablet-savvy violinist playing onstage. Not quite. So the quick-thinking Dalton, grabbing a rehearsal break in the darkest, deepest part of Orchestra Hall (where Wi-Fi reception is spotty at best), digitally fused her scattered crew together to put Bates’ written revisions into place.

Her son and copyist was at the highest, tallest part of Lake County, “falling 150 feet, when we got the word from the [CSO] library that Mr. Bates had decided to change the last two lines. My son gets the call from me, backing up the librarian’s email to him, that something needs to be done right now. It’s just come up. He’s at Great America and doesn’t have his laptop, so he calls the assistant,” Dalton adds, referring to Bergelson’s daughter, who was readying for a salon appointment.

Mother and daughter kicked into action, Bergelson remembers: “We hadn’t left yet, so I told Allie, ‘Grab your computer and get in the car and call Graham.’ I had my phone, which would give us [an Internet] hotspot, and then we could use the phone through her computer to get into the Dropbox [shared storage files] that kept the music.”

While the hair stylist clipped and trimmed, Bergelson’s daughter cut and pasted, using her laptop’s Illustrator software to merge Bates’ changes into Dalton’s score. Bergelson beams at the memory: “We ended up at the beauty parlor coming up with a whole new procedure.” Unfortunately, “the beauty parlor didn’t have Internet, so we were still using my phone” and “we were having a lot of trouble getting [Dalton’s revised score] to attach because it was 84 pages.”

Back at Orchestra Hall, Dalton rushed Team Bergelson’s quick handiwork into her display. “The Wi-Fi signal is really bad. … I should go over to Starbucks, really — carry my tablet over there.”

Where she could try the new “Madrugada” blend.

“How do I look to you?”

Beyond Dalton and Bergelson’s “reversible friendship of mentor and student,” as the stronger of the violinists if second of scientific minds considers it, and beyond the on-call family of tinkerers and web-savvy copyists, a crowd of supportive colleagues is stepping forward, beginning with musicians, maestro and management at the CSO.

“I don’t really deserve it.” Dalton verges on apology. “I’m thinking it’s because people love their music and want their artists to play. It could be them. It could be anybody who ends up in my position, and so they want it to work for me, because they want it to work for them. They want this sociological opportunity to exist — within the musicians, with the management, with the public. It’s healthy. It’s enlightened.”

A view from the terrace seats of Dalton’s touchscreen display, designed according to her “100 percent invisible” standard. | Photo: Andrew Huckman

Maestro Riccardo Muti is on board. Dalton talks about her recent visit with the CSO’s music director and their shared sense of progress. She started by asking him a question. “‘OK, I’ve finished a month onstage. It’s looking good. They’re a few things more, but how do I look to you?’ And he said, ‘You’re the picture of artistic integrity. Go forward.’”

It’s a familiar sentiment in the Muti family, a take shared by Cristina Mazzavillani, the conductor’s wife, when Dalton wondered about persisting. “She said to me, ‘Oh, Alison, you have to do it. You have to do it for all of us. Just find a way, because it could happen to anybody and somebody has to do something.’”

Dalton still weighs Mrs. Muti’s determination with Lady Solti’s reflection. Two friends, two eras, two first ladies of the CSO with the orchestra’s best interests at heart.

“And, you know, they’re all right. To the world, what both of them had to say — absolutely proper. So what do I do with all of that? It’s to keep going, like Mrs. Muti says, and to do it so well that Sir Georg would approve.”

Dalton still hews to what she’s always valued. When concerts end, she swiftly retires her reading glasses and rises for bows. Right wrist tucked behind her back. Stern visage and firm stance. That’s the CSO tradition.

Sometimes it tests the violinist’s evolving perception. As she challenges herself behind a vivid monitor, what’s always been central is now often difficult to discern, but she grasps the changes that come on all sides.

In the audience, you sense her subtle glow.

Andrew Huckman is a Chicago-based lawyer and writer.

TOP: Alison Dalton with her specially built “Fascinoter.” | Photo: Andrew Huckman