Ask Peter Conover about his duties as the Chicago Symphony Orchestra’s principal librarian, and he gives a well-rehearsed if apt answer: “To make sure we have the right music in the right place at the right time. If you can pull that off, then that’s pretty much 99 percent of the job.”

Overseeing a facility on the lower level of Orchestra Hall that houses more than 5,000 scores, with additional older ones in the orchestra’s Rosenthal Archives, he explains, “It’s a large library. It’s probably not the largest in the world, but it’s among the largest.”

He heads a staff of three, who are considered orchestra members, and their duties never stop regardless of the season. At any given moment, they are working on the music for that day’s concert or rehearsal, or concerts a few months or a year away. In addition to purchasing or renting scores, they prepare the scores for performance by, for example, correcting errors (orchestra librarians have a shared database of such published mistakes), cutting and pasting parts so that page turns are easier and inserting bowings. The leader of each string section decides on bowings for every work (essentially indicating down- or upstrokes for each bar) and marks his or her part accordingly. To ensure that the other musicians in that section are in sync, a librarian makes sure those bowings are transferred to their parts.

Although many orchestra librarians are former symphonic players, no set career path exists to obtaining such a post. “There is no place in the country where you can take classes and do this,” Conover said. “Many of us have had the same path: Basically, we stumbled into it. We were dragged in somehow.”

After graduating from the Philadelphia College of Performing Arts in 1984, the Bucks County, Pa., native worked as a freelance bassist with an array of ensembles in the Philadelphia area. Two years earlier, he had heard that the Delaware Valley Philharmonic’s part-time librarian position was open. Because it paid an extra $50 a concert — money that would come in handy — he went to the conductor and asked for the job, even though he had little in the way of experience.

After meeting Clinton Nieweg, principal librarian of the Philadelphia Orchestra, Conover began working in 1984 with that top-level orchestra’s library, first as an apprentice and later as a part-time assistant. In addition, for three summers during that time, he served as librarian for the American Institute of Musical Studies Orchestra in Graz, Austria, for which he also played double bass. In 1990, he gave up the bass for good, and became the full-time principal librarian of the Phoenix Symphony. Three years later, Conover took over as principal librarian of the larger Houston Symphony, which was then headed by conductor Christoph Eschenbach. In the summers of 1995 through 1997, Conover worked at the Grand Teton Music Festival in Wyoming. He came to Chicago in 1998.

How closely do you work with the conductors?

It varies a lot. Certainly, in this day and age, there are a lot more who prefer to e-mail us or call us directly. I’ll be sitting there at my desk and the phone will ring, and I’ll see that it is an English country code, and it will be Sir Mark Elder on the phone. He’ll talk about his upcoming concerts. He may have just finished a performance and he had it on his mind and decided to chat for a while. James Conlon [music director of Ravinia, the CSO’s summer home] and I e-mail pretty regularly. A lot of the other conductors, you have to go through their agents or you have to go through our artistic department, who goes through their agents. So then there’s a little bit of telephone tag. A lot of our conductors come back year after year, and if they’re here during the season and I already know what they’re going to be doing the subsequent season, I’ll pull them aside for five minutes while they’re here and say, “Do you have any special needs or requirements for what you’re doing with us next year?” For example, Bernard Haitink was here this spring, and he is doing [Richard Strauss’] An Alpine Symphony with us next year [April 28-30]. I know what the questions are to ask about Alpine Symphony, and I said, “So how do you want to do this? Do you have any special preferences?”’ It’s great just to be able to get it from the horse’s mouth.

What else to you need to know other than what edition they want to use?

For example, An Alpine Symphony has extra brass. It’s written a certain way, but sometimes orchestras try to do it with less, because they can save some money. When you’re doubling horns four ways or three ways, you can save a little money by doubling it two ways. It sounds almost the same but there are fewer bodies. So you ask him a question like that. Certainly, editions is one of the bigger questions to ask, and it has become very complicated because there used to be one edition of everything, and now there are multiple editions of almost everything. I had my meeting with Maestro [Riccardo] Muti for all of his programs for next season [earlier this month], and that was great to be able to run down the list and go bang, bang, bang, and then not have to go back to him later. Besides editions, a common question is string reductions. Obviously, concerti are often played with reduced string complements. So you want to ask the conductor: What does he or she want?

You’re asking so you know how many parts you’re going to need?

We collate that information. We need it for ourselves but then we also need to share it with the personnel manager. Because we have so many people in the orchestra, their rotation varies. There is a whole department that takes care of that. So if they know in a certain week that they’re only going to need 14 violins instead of 16, then two people can be on release that week.

And you actually tell the personnel manager?

All of our programs are listed on an electronic database that we use throughout the building, and I can go in there and punch in the string reductions for the whole season. Then they don’t have to ask us. That’s made life a lot easier.

Don’t conductors sometimes supply their own scores?

They do, indeed.

How often does that happen?

Twenty percent of the time. Our orchestra is very good about accepting other people’s materials. Some orchestras are a little more cranky about it. Our guys will go with the flow. [Wagner’s] The Flying Dutchman [which the CSO will perform Aug. 15 in a concert version at Ravinia] — these are the parts that James Conlon used at the Los Angeles Opera. So even though we have our own set of [parts for] Flying Dutchman, this is what we’re going to use, because it worked for James Conlon in Los Angeles, and it’s going to be perfect for us at Ravinia. Except that we have to restore a cut that was made in Los Angeles that we’re not taking in Ravinia. Another project that we just finished working on is a Zemlinsky piece [Die Seejungfrau] that Conlon is conducting [July 29 at Ravinia]. It’s not actually his set [of parts], but it’s a set that he used for a prior performance. He doesn’t own it, but he has access to it, and it’s reserved for him. That happens pretty frequently. During our recent French festival with Esa-Pekka Salonen, he was doing a lot of the same repertoire in London with his orchestra there. So we got the [parts for] Pelléas et Mélisande and L’enfant et les sortilèges from London, and that really helped us a lot, because that’s a lot of music. We played a Debussy piece for which we sent them the parts afterward. We don’t generally lend out our parts, but they had been so nice to us that we wanted to reciprocate.

You have more than one edition of certain works in the library, yes?

We definitely do. We did the Eroica Symphony with Ludovic Morlot a few weeks ago. Most of the time when we do Beethoven, we still use the old Breitkopf & Härtel edition. But many people like to use Bärenreiter. When we did the cycle with Haitink a few years ago, we did them all with Bärenreiter. So now we have Bärenreiter edition for all the Beethoven symphonies, and that’s what Ludovic wanted to use with us.

String section leaders are responsible for the bowings for each piece, but who is responsible for marking them into the parts?

Great question. The principals will mark their own parts and then we’ll copy those markings into the section parts. Even in the days of copiers and computers, we still do it more or less always by hand in pencil, because it’s the most efficient way to get bowings into parts. They have to be able to be changed. When you have photocopied bowings, it’s much harder to change in rehearsal.

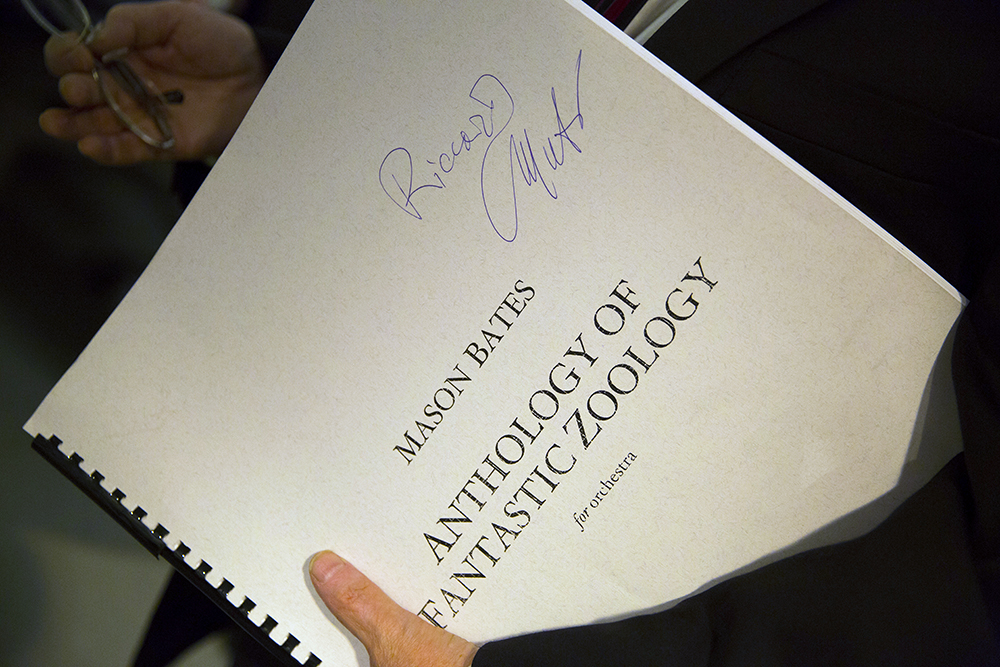

Maestro Muti holds a copy of the score for Mason Bates’ Anthology of Fantastic Zoology. | © Todd Rosenberg Photography 2015

And it’s possible they would change something in rehearsal?

It’s almost guaranteed. The story I like to say is that you can play the same piece with the same orchestra with the same conductor in the same hall a year after it was played, and they will change bowings, because someone will have an insight. Or someone will decide that something works better. So a bowing is very fluid.

Is difficult to find scores for rarely performed works?

On the surface, no, it’s not that difficult anymore.

So there are not out-of-print editions?

Nobody asks for something that hasn’t been performed someplace, and especially with recordings or the Internet, it’s not hard to find out who has played this piece before. If someone comes to you and says, “I heard this recording of Josef Hoffmann’s Symphony No. 5.” And you say, “Who made the recording?” And they say, “Well, it was the Slovenian Radio Symphony.” Well, we could contact the people at the Slovenian Radio Symphony and ask them where they got the parts from. They might be dreadful. They might be bad manuscripts, but the fact is, they are out there.

Do you work with music publishers to buy scores or do you work through dealers?

We buy music and we rent music. It’s two different worlds. In terms of purchases, we have a retailer who is more or less a clearinghouse for the music publishers that will sell us music. But in terms of renting music, which is mostly the copyrighted material, so we’re talking about music that has been written since 1923, we deal with the U.S. agents of the world publishers, and there are not that many anymore. There used to be many. But now it’s European American Music, Boosey & Hawkes and G. Schirmer — they are the three big ones. And Edition Peters, you could add in there, too. Between those, we can pretty much get everything that we need. They publish their own music, and they are the agents for most of the foreign publishers.

How are royalties paid for copyrighted music?

In the United States, there are two major associations, ASCAP [American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers] and BMI [Broadcast Music Inc.], and they act as a clearinghouse for the music that is under copyright, where royalties have to be paid to estates or the composers. What we do with those guys is that we have a blanket license that we purchase each year. It’s pretty big bucks. It’s well over $100,000.

Based on the size of the orchestra, your audience size and all that?

Yes, the budget, the anticipated audience and things like that. But it’s a bargain, though, because you could theoretically not get a blanket license and apply for one each time you played one of those [copyrighted] pieces, and it would cost a lot more.

Typically, before concerts you see the librarian come out and put the score on the conductor’s music stand.

I like tell people, there are three parts to our job: acquisition, preparation and distribution. The distribution is the part you are referring to. Frankly, it’s the only time the public really sees us. We’ll run around with the crew and help with stage changes, but really the only time is when we come out five minutes before with the conductor’s score. It’s kind of a ceremonial position. Other people could certainly do that, but it’s a nice opportunity for us to have that last-minute conference with the conductor. It’s a last chance for us to look at the stage and make sure everything is ready.

When do you give the musicians their music?

As early as possible. A rule of thumb is five weeks before [a concert]. We have players who will certainly ask for music months and months in advance, especially if it’s a piece that they’re familiar with that’s difficult or a piece that they’re unfamiliar with that they think is going to be difficult. Sometimes, we’re not ready to supply that part to them, but we can give them something to look at or practice from.

For a new piece like Mason Bates’ Anthology of Fantastic Zoology, composers will typically sit in during rehearsals and often make changes as things go along.

What happens? Are the players expected to pencil those changes in or do you have to somehow tweak the parts?

It has a lot to do with timing. He came to us very late with some changes. Basically all we could do at that point is put out a list for the players, who would then pencil the changes in themselves so it was in their part when they rehearsed it. But then, after rehearsal, we had almost 24 hours until it was going to be played again, so we made some changes in the first violin parts while they were rehearsing [another work]. But he also put out another set of memos to the orchestra with changes and then at the end of this second rehearsal, we got a note from the one of the principals, who said that this B should be a B-flat. That’s why those second-violin folders are sitting there, because I just changed the note in the parts. They could have done it themselves, but it was probably at the last minute of the rehearsal, so there is no reason why we couldn’t do it, and it will be all ready for them tomorrow.

We’re seeing now some chamber ensembles and individual artists using electronic tablets and the like. Has there been talk of switching over to electronic music?

Absolutely, great talk. Part of it is that for a while there was a company called eStand that was actually based here in Chicago and the fellow who was heading that company was really, really anxious to have the Chicago Symphony be one of the first major orchestras to use electronic music stands. He got a lot press at one point because Itzhak Perlman conducted us at Ravinia, and his score was on an electronic music stand. It’s not a bad concept, and I think it’s not a question of if. It’s more a question of when.

But the fact is that paper is a very reliable medium. It has very few drawbacks. They talk about a lot of the things they want to accomplish with electronic music stands, but here’s example I usually use. If you had an orchestra full of electronic music stands, and you overcome all the other obstacles and you’re in the middle of a performance and you’re the second trombone player and your screen went blank. OK, I know how to reboot it. But in the meantime, the performance is going on. Who’s fault is it? Is it my fault? Is it his fault? Is it the manufacturer’s fault? You’ve got a lot of places where there could be a problem.

With paper, pretty much it’s all or nothing. For example, the other day, we had a power failure, and all the lights went off. The orchestra was playing at that point, and they actually finished the piece because they were about four bars from the end, which was pretty amazing. That was the case where lights went out and everyone was in the same boat. No one was to blame or was individually affected by it. Say, wind comes by and it blows your part [off your stand]. That’s one of the drawbacks of paper. When we play at Ravinia or outside, we use wind clips. It’s not great. It’s hard on the music and it’s a little bit awkward, especially if it is a fast page turn, but still it’s something that everyone can more or less work around because they’ve been doing it for decades, if not centuries. With the electronic music stand, if you were outside, you might have glare or you could see it, but your stand partner couldn’t see it.

I think it’s something that youngsters who have grown up with computers will be much more apt to use. I think quartets or chamber ensembles are better suited than a symphony orchestra. Pit orchestras, whether it‘s for Broadway or opera, are a good place to start. Also, universities where you’re going to have youngsters who are more interested in trying this technology.

Kyle MacMillan, former classical music critic for the Denver Post, is a Chicago-based arts writer.

TOP: Peter Conover, CSO principal librarian, juggles an armload of scores to be packed after the orchestra’s winter 2014 tour. | © Todd Rosenberg Photography