For his final commission as the CSO’s Mead co-composer-in-residence, Mason Bates summons the sprites, griffins and serpents of Jorge Luis Borges for his Anthology of Fantastic Zoology. Dedicated to Maestro Riccardo Muti, this fanciful suite leaves the laptop, Bates’ frequent instrument of choice, tucked backstage in its sleeve, as the composer elects instead to unleash purely acoustic creatures through the aisles of Symphony Center. (The work will have its world-premiere performances June 18-20.)

Music writer Doyle Armbrust recently connected with the zookeeper himself, to get the scoop on this carnival of mythic beasts:

Did you come across Borges’ anthology, Manual de zoología fantástica, as a father looking for books for his kids?

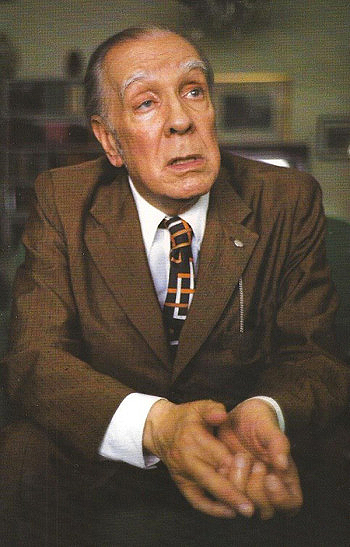

Jorge Luis Borges wrote Manual de zoología fantástica, the inspiration for Mason Bates’ latest work.

Bates: I actually found it before I had kids. Now that I’m reading Lord of the Rings with them, though, I look back and see that it does have a childlike component to it. I came across Borges as an English major at Columbia [University], some 20 years ago, and I was drawn to his collision of non-fiction writing style and completely wild, magical realism.

How did you excavate it for source material?

There’s a chick-and-the-egg aspect to my music and the forms it inhabits. On the one hand, a piece like Alternative Energy or this Anthology of Fantastic Zoology are dramatic, programatic pieces. On the other hand, I’m attracted to these forms because they are the kind of music I’m looking to write. For this piece, I was looking to write one of those giant, ballet-type suites in which you have lots of little movements that are all very colorful and very distinctive. I wanted to challenge myself to write memorable music that had a surreal, psychedelic component to it.

A lot of new music doesn’t put a priority on being memorable in the way that the music of a different era might have. I wanted to see how I could create a sprawling form and have it all come together at the end. In the Anthology, I found the perfect vehicle for that, going through Borges’ book and picking out specific animals that suggested interesting musical realizations.

Given your laptop savvy, was it a specific constraint you placed on yourself to not include electronic elements in conjuring these mythic creatures?

It’s a natural question because, for me, electronics have become a new section of the orchestra. It’s almost a given that you should be able to access that sound world. However, there are advantages to having a diverse catalog as a composer. I have several symphonies for orchestra and electronics, and I always figured I would have an electronic component, but for this piece, I thought, let’s have it entirely unplugged and see where that takes me. What I’ve found in my acoustic pieces is that I’ve pushed into new sonic territory with the instruments themselves, say, with my Violin Concerto, where the string section becomes a percussion ensemble. In the Anthology, there are hugely imaginative effects that I don’t think I would have come up with otherwise.

Like the offstage violins?

Even the onstage ones. I’ve spent the past couple years at the symphony looking at the strings and thinking, why can’t we activate those like dominoes? Why can’t we have a riff whip through the section in an almost visual way? You can imagine material spreading outwards from the conductor’s podium, running down the first violins or the cellos.

Mason Bates appears via video at the MusicNOW performance of his The Rise of Exotic Computing. | © Todd Rosenberg Photography 2014

You haven’t made any secret about your admiration and affection for Maestro Muti, to whom the piece is dedicated. How did he help inspire the piece?

In addition to being a phenomenal musician and conductor, Maestro Muti is a master dramatist. He brings theater to the concert hall, and that’s something I’ve embraced in my music over the years — having the symphonic experience become a journey that leaps off the stage. He reminds us that the symphonic space is a highly theatrical space.

Do you see a life for The Anthology of Fantastic Zoology beyond the concert hall, say, in a Carnival of the Animals realm?

I’ve gotten to a place where I always think about the life of the piece, given that living composers are typically programmed alongside historical pieces. For instance, [Debussy’s] La mer hasn’t been programmed with my water symphony, Liquid Interface, nearly as much as I would have thought. In terms of young audiences, it’s not a light piece and has big stretches that are thick territory, but I could see a ballet coming out of it because it’s so evocative. I don’t know if my kids would last through all 30 minutes of it, though!

As you look back on your time with the Chicago Symphony, starting with your first commission, Alternative Energy, do you see a tangible evolution toward this final work of your residency?

For me, a commission sears you together in a creative moment with an ensemble. It begins a relationship. To have the CSO perform five large pieces over the past five years, I can look back and see that I’ve embraced the symphonic space. I’ve come to realize that there’s a real opportunity, artistically, to explore the sprawling, narrative approach of the 19th century with entirely new sounds, whether electronic or acoustic. There is so much music today, music that I love, that is process-driven, whether it be post-serial or minimalist music. You don’t see many pieces now that have a big formal scope, and for me, working with Maestro Muti and the CSO has been a real evolution in seeing that possibility. In the concert hall, you can go to a deep, surprising place and blow minds.

The violist of the Chicago-based Spektral Quartet, Doyle Armbrust also writes for Crain’s Chicago Business and Q2 Music.

TOP: Mason Bates at his laptop during a MusicNOW concert, conducted by James Feddeck, in September 2014. | © Todd Rosenberg Photography 2014