French composer Bruno Mantovani is on a roll. Seven of his works received premieres over the last year, and guest conductor Marin Alsop and the Chicago Symphony Orchestra will debut an eighth during a set of concerts Oct. 18-20. Such productivity is especially impressive, considering that he also conducts eight to 10 concerts annually with groups such as France’s Ensemble Intercontemporain and has served as director of the prestigious Paris Conservatory (Conservatoire) since 2010.

“For me, it’s the same job to conduct, to compose and to be the director of the Conservatoire,” he said. “You have an idea, and you have to put in the right way and to give a concrete sense. When you are writing music, you have an idea, and you have to develop it with the orchestra, with the instruments. When you are head of an institution like the Conservatoire, you just want to have a precise vision about you want for the students and you do the thing. So for me, everything is the same job, and it’s not metaphorical. It’s a real feeling in my life.”

Mantovani’s new work for the CSO, titled Threnos, was commissioned as part of the orchestra’s commemoration of the 100th anniversary of the World War I Armistice. A threnos (derived from the ancient Greek word threnoidia), also known as a threnody, is a song or hymn of mourning. Typically, such works are slow and elegiac, but Mantovani wanted to create a threnos that also is what he calls “fast and active.” “That can sound like a contradiction, a paradox, but I think paradox is a good thing in music,” he said. “Paradox is one of the motors of my music.”

Writing a work related to World War I was not a stretch for Mantovani, 43, who likes to compose pieces that have extra-musical connections. His paternal grandparents fled the fascism of Italy (that’s the derivation of his last name) and his maternal grandparents fled the oppression of Franco’s Spain, with both families immigrating to France. Because of this history, he believes it’s important to have a connection to his origins and to understand the politics and upheaval that ultimately led to his birth in France.

In March 2009, Pierre Boulez conducted Mantovani’s Streets for chamber ensemble as part of MusicNOW, the CSO’s contemporary music series. In addition, the composer has had works performed by other American ensembles such as the New York Philharmonic. But Threnos is the first piece that he has written especially for an American orchestra.

“I have a really good remembrance of the concert with Boulez and the Chicago Symphony,” he said, “Of course, the orchestra is fantastic. A lot of American orchestras are just crazy amazing, but I remember the very nice attitude of the orchestra — musicians really wanting to do their best. When the orchestra proposed my writing a piece, I was really, really happy, because of the good feelings I had with this orchestra. So I’m happy to come back.”

Some of his works draw on jazz, popular music and music from other parts of the world like Armenia. “For me, the model of that is Maurice Ravel,” Mantovani said. “If you see that catalog of pieces of Ravel, a lot of them are references to Spain: Bolero and Rapsodie Espagnole or Jewish music or Greek music or jazz. But it never sounds like jazz or Spanish music or Greek music, it sounds like Ravel’s music. For me, the purpose of this game is not to make a collage, it’s not to make only references.”

Mantovani also has written several pieces that look back at the work of famous classical composers, including Ravel, Franz Schubert and Robert Schumann. “Sometimes I say that I’m writing like a musicologist,” he said. Regardless of what other musical sources he draws on, such influences are just a starting point from which he tries to build something that is distinctively his.

Asked to describe his musical language, the composer didn’t hesitate: “I like fast music. I like energy. I’m not a contemplative guy.” Mantovani also pointed to the influence of his native country. “Even if my blood is not completely French, my music sounds French, because my mother language is French,” he said. “There is a very strong relationship between the mother language and the way of writing music. Without being too much of a caricature, I like harmonies, I like very transparent orchestrations.”

At the same time — back to the idea of paradox — he feels a strong affinity for Austro-Germanic composers such as Beethoven, Berg, Mozart and Schumann.

“I think today it is not so easy to define a composer without using the word ‘synthesis,’” he said. “During the 1950s and ‘60s, there were personalities very clearly defined by a school — Boulez, [Luciano] Berio, [Karlheinz] Stockhausen and [György] Ligeti. Today it’s much more difficult. All composers of my generation and younger are taking ideas from here and from some other places and making syntheses between all these heritages that we have.”

Former classical music critic of the Denver Post, Kyle MacMillan is a Chicago-based arts journalist.

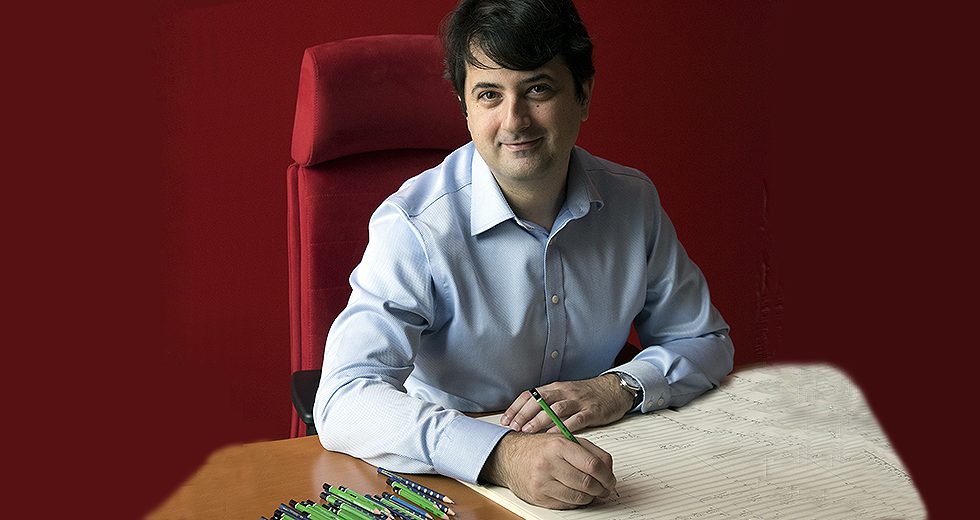

TOP: Bruno Mantovani by Ferrante Ferranti