At first glance, George Gershwin and Maurice Ravel might seem to occupy two different musical worlds, yet they both shared a passion for jazz.

In the ’20s, jazz was still a relatively new genre but much as aviator Charles Lindbergh had in 1927, it crossed the Atlantic and landed in Paris to great acclaim. In 1928, the French composer made his first and only trip to America, embarking on a four-month concert tour that would take him to more than 20 cities, including New York, Toronto, Vancouver, San Francisco and Chicago (where Ravel conducted the Chicago Symphony Orchestra in a program of his own works on Jan. 20-21, 1928). During this tour, Ravel introduced his Rapsodie espagnole, Daphnis et Chloe Suite No. 2 and La valse to a wider audience. Furthermore, he also had the chance to explore one of his latest obsessions: American jazz.

While in New York, Ravel went to see Gershwin’s new musical Funny Face and declared himself “enchanted.” He expressed interest in meeting Gershwin and hearing him play the Rhapsody in Blue and other jazz-influenced works. (Led by guest conductor Ludovic Morlot, the CSO will perform works by Gershwin and Ravel, with pianist Denis Kozhukhin as soloist, in concerts June 4 and 6.)

Like his fellow French composers Satie and Debussy, Ravel was fascinated by American popular music including ragtime and jazz, according to Howard Pollack, author of George Gershwin: His Life and Work. “That had pretty much been in the air in Paris for a while,” Pollack wrote. “[Ravel] had already shown a predilection for using some of that sort of jazzy idiom in his Sonata for Violin and Piano,” completed in 1927.

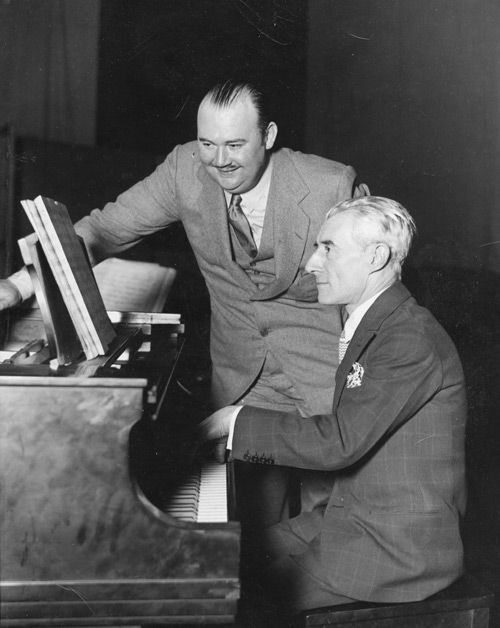

At a party held in his honor by soprano Eva Gauthier, Ravel celebrated his 53rd birthday on March 7, 1928. One of the guests that evening was Gershwin. During the soirée, the young Broadway songwriter entertained Ravel and the other guests with an impromptu performance of Rhapsody in Blue and a selection of songs including “The Man I Love.”

Gauthier later wrote: “The thing that astonished Ravel was the facility with which George scaled the most formidable technical difficulties and his genius for weaving complicated rhythms and his great gift of melody.”

Apparently, the admiration was mutual. Gershwin, who was always looking to learn new styles and techniques, asked the French master to give him lessons in composition. According to Gauthier, Ravel gave serious consideration to Gershwin’s request, but decided that “it would probably cause him to write ‘bad Ravel’ and lose his great gift of melody and spontaneity.”

Ravel spent several nights with Gershwin, listening to jazz at the Savoy Ballroom in Harlem, where dancers did the Lindy Hop to hot jazz from some of the nation’s greatest bands. Ravel also visited Connie’s Inn and the nearby Cotton Club, where he heard Duke Ellington and his orchestra.

“It’s surprising to many people that Gershwin would have some exchange with Ravel, but Gershwin actually was very knowledgeable about contemporary music,” Pollack wrote. “As a famed and well-known and brilliant composer, he had access to meet whichever composers basically he wanted to meet. And he did, in the course of his life. He was very knowledgeable about their music.”

Before leaving New York for Kansas City to resume his tour, Ravel further explored his interest in jazz by visiting the Liederkranz Hall to hear famous bandleader Paul Whiteman, “The King of Jazz,” and his orchestra in a recording session with jazz trumpeter Bix Beiderbecke.

That same month, Ravel urged Americans to “take jazz seriously,” in an essay published in magazine Musical Digest. Ravel wrote: “Personally I find jazz most interesting: the rhythms, the way the melodies are handled, the melodies themselves. I have heard some of George Gershwin’s works and I find them intriguing.”

Some of Ravel’s later works show the influence of the jazz he heard in America. One is the Piano Concerto for the Left Hand (which the CSO will perform June 4 and 6), completed in 1930. In this work, two themes are presented in the introduction, one of them “derived from jazz, with ‘blue’ notes and syncopation,” observes Arbie Orenstein in Ravel: Man and Musician.

Another jazz-influenced Ravel work is the Concerto for Piano in G Major, completed the following year. Here, the influence of Gershwin is easier to detect. Pollack writes that “Gershwin unquestionably influenced Ravel’s later work, in particular the Piano Concerto in G Major, completed in 1931, a work long regarded as a kind of homage to Gershwin, though its debts to Satie and Milhaud are perhaps greater still.”

Gershwin himself visited Paris later in 1928. The trip inspired him to write An American in Paris, a tone poem intended to evoke the sights and sounds of a busy Paris street. Interestingly, Gershwin did not name Ravel as an influence on this work, but rather stated that he composed it “in the manner of Debussy and [Les] Six.”

“Debussy was a great influence on Gershwin, a paramount influence,” Pollack said. “Whether Ravel was influential on Gershwin would be hard to say, but Debussy clearly was a great influence. It’s there in the music, and it’s there in his comments.”

Yet Gershwin greatly admired Ravel’s technical mastery. According to Pollack, there is a real aesthetic difference between the two. He described Ravel as “‘the aristocrat of music,’ and Gershwin is sort of ‘the man of the streets.’ There’s really an interesting dichotomy there. They admired each other, but probably from some distance.”

Louise Burton, a regular contributor to Classicalite, is a Chicago-area arts writer.