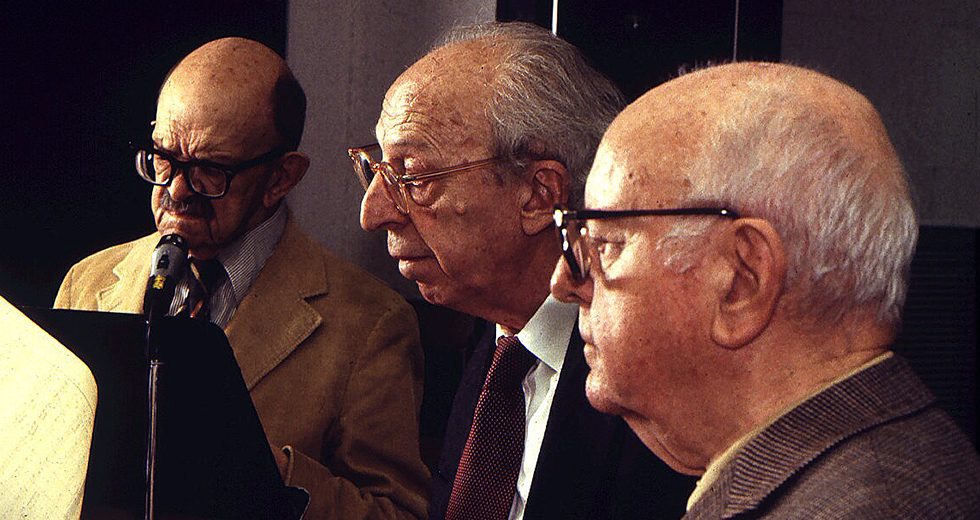

In the nation where it was composed, American orchestral music remains significantly underperformed. In fact, works by other than a handful of familiar historical figures such as George Gershwin and Leonard Bernstein and living composers such as John Adams are hardly heard at all. Once well-respected 20th-century American masters like David Diamond, Roy Harris, Roger Sessions, Walter Piston and William Schuman are now often overlooked.

According to the most recent data compiled by the League of American Orchestras, no Americans crack its top 10 list of the most-performed composers. Among the top 25, just three American names can be found: Aaron Copland, George Gershwin and Leonard Bernstein. (Igor Stravinsky, who became a naturalized American in 1945, is also included, but he wrote many of his most iconic works as a Russian.)

“You have all these guys — really strong composers. They really do deserve to be heard,” said Marin Alsop, music director of the Baltimore Symphony Orchestra and São Paulo Symphony Orchestra in Brazil.

Under Riccardo Muti, the Chicago Symphony Orchestra has put a strong emphasis on emerging American composers. Figures such as Samuel Adams, Mason Bates and Elizabeth Ogonek have served as Mead composers-in-residence, with each receiving musical commissions and performances in conjunction with the post. During the 2018-19 season, the CSO is going even further, presenting a series of works by important American composers, including some rarely heard selections.

This lineup of 20th-century American pieces begins Oct. 18-20 when Alsop guest conducts the CSO in Copland’s Symphony No. 3, which she regards as one her favorites in the form. It is one of four works on the program that are part of the orchestra’s season-long focus on peace and reflection to mark the 100th anniversary of the end of World War I.

The piece, which the Boston Symphony premiered in 1946, makes use of the theme from the composer’s beloved Fanfare for the Common Man, written in response to America’s entry into World War II. “I think it’s a virtuosic piece, so it’s perfect for the CSO,” Alsop said. “Every single instrument is featured in a major way. It is a piece that will register with the audience and the musicians as well.”

Although not exactly a rarity on orchestral programs, Copland’s Third Symphony is not frequently heard, either. The CSO has performed the piece on only two occasions in the past 35 years: a 1983 concert at the Ravinia Festival and at subscription concerts in 2007 with guest conductor Alan Gilbert.

Alsop, recently named as the next chief conductor of the ORF Vienna Radio Symphony Orchestra, cited several reasons the Symphony No. 3 might not be played more often, starting with its sheer difficulty. “In terms of tessitura, it’s the highest piece in the repertoire,” she said. “It’s a really big and challenging work, so the orchestra has to be able and willing and committed.” In addition, it calls for augmented forces, which means an added expense. Because the symphony is still under copyright and not in the public domain, rental fees have to be paid — yet another cost.

At the same time, composers have a tendency to go in and out of fashion. Often anniversaries provide a big boost. During the 2018 season, for example, classical-music organizations worldwide have celebrated the 100th anniversary of the birth of Leonard Bernstein, with thousands of concerts devoted to his music, including some of his most obscure creations. “Bernstein had a big year, so maybe Copland got the back seat for a while,” Alsop said.

She suspects that one of the reasons for the lower profile of American music is the paucity of American conductors heading top orchestras. All of the so-called Big Five American orchestras — Boston, Chicago, Cleveland, Philadelphia and New York — are led by European conductors who might not necessarily have an affinity for such repertoire. “Not that European conductors and music directors aren’t wonderfully capable of doing American music — they certainly are for some fantastic performances.” Alsop said. “But I think as a defining identity for an orchestra, a non-American would not gravitate toward that.”

Regardless who is at the helm, she would like to see American orchestras make a commitment to playing historical American works more consistently. “Repertoire, like everything, becomes more comfortable the more it’s done,” she said. “If you only play big American works once or twice a year, they don’t become go-to works for the audience or the musicians. I do think we just need to try to reassess our programming and be more inclusive on every level, not just for American works but works by women composers and African-American and Latino composers. There’s a lot of great stuff out there.”

Other American works on the CSO’s 2018-19 schedule:

- Jan. 10-12, Charles Ives’ Variations on America (orchestrated by Schuman) and William Grant Still’s In Memoriam: The Colored Soldiers Who Died for Democracy, with Bramwell Tovey as guest conductor: The latter work was composed in 1930 by perhaps this nation’s most celebrated African-American composer as a tribute to black soldiers who fought in the Civil War. “I think we’re starting to see his music, as well as the music of Florence Price and some other African-American composers, getting onto the mainstream subscription series now — rightfully so,” Alsop said. “We have a lot to do, still, in terms of opening the doors at our symphonies to diversity and a place of inclusion.”

- Feb. 21-23, William Schuman’s Symphony No. 9 (La fosse Ardeatine), conducted by Muti: This will mark the CSO’s first performance of this work. It was inspired by one of Italy’s most significant World War II monuments, which the composer and his wife visited in 1967. After the killing of more than 30 German S.S. officers by the Italian Underground in March 1944, the Nazis took 335 Italians to the Ardeatine Caves outside Rome and shot them, setting off bombs in an attempt to conceal the atrocity. “Somehow, confrontation with the ghastly fate of several hundred identifiable individuals was more shattering and understandable than the reports of the deaths of millions, which by comparison, seem abstract statistics,” Schuman wrote in notes that accompany the work. Alsop praised Muti’s choice of this symphony, which bridges two cultures. “Accessing this American music through his own [Italian] heritage is absolutely brilliant,” she said. “I think that is really fantastic.”

- June 13-15, Gershwin, An American in Paris, conducted by Muti: Aside from two compositions by Stravinsky (both written before he emigrated to the United States), the most frequently performed American work is An American in Paris. Composed in 1928, the well-known, jazz-influenced piece evokes the bustling sights and sounds of Paris, including prominent automobile horns.