If you drive down any road in rural America — it doesn’t matter in which state — eventually you’ll get to a barn where antiques are sold. There you’ll find bits and pieces of Americana: butter churns, buggy whips, circus posters, ancient farm tools, maybe a Burma-Shave sign or two, women’s bonnets, men’s Stetsons, cast-iron skillets and quilts of every size and description. If you took all of this and displayed it in a European art museum, you’d have a visual equivalent of Charles Ives’ Second Symphony.

The symphonic form is a European creation, yet Ives, who was fluent in European harmony and counterpoint, produced works that are thoroughly American. Like Emerson, Thoreau and Twain, Ives is an American original, the first thoroughly 20th-century composer this nation produced. (The Chicago Symphony Orchestra will perform Ives’ Symphony No. 2 in concerts April 24 and 26 and for two Beyond the Score programs on April 25 and 27.)

Charles Ives was born in 1874 in Danbury, Conn., to a father who had been a bandmaster in the Civil War and who was the major musical influence on his son. The senior Ives continued on as a bandmaster in Danbury and was an inquisitive man, at least as far as music and sound were concerned. He would have his family sing “Old Folks at Home” (a.k.a. “Swanee River”) in E-flat while he played the accompaniment in the key of C. As Charles Ives later wrote, “To stretch our ears and strengthen our musical minds.”

Ives’ father introduced him to the music of Bach and Beethoven, schooled him in harmony and counterpoint, and saw to it that he learned several instruments. When he was 13, Charles was the playing the organ at the West Street Congregational Church in Danbury. He graduated from Danbury High School, went on to Johns Hopkins Preparatory School, and at 20, entered Yale University. There he studied composition with Horatio Parker.

Ives’ father introduced him to the music of Bach and Beethoven, schooled him in harmony and counterpoint, and saw to it that he learned several instruments. When he was 13, Charles was the playing the organ at the West Street Congregational Church in Danbury. He graduated from Danbury High School, went on to Johns Hopkins Preparatory School, and at 20, entered Yale University. There he studied composition with Horatio Parker.

Parker had studied in Germany and was an ultra-conservative, by-the-book kind of guy, not at all like Charles’ father, George. “Parker was a composer and Father was not,” Charles wrote. “But from every other standpoint, I should say that Father was by far the greater man.”

Not long after the young Ives entered Yale, his father died. It was a tremendous loss but Ives continued at Yale. After graduation, he moved to New York City, eventually taking up employment as an actuary. “Father felt that a man could keep his music interest stronger, cleaner, bigger and freer if he didn’t try to make a living out of it,” he said.

Incredibly successful in the insurance industry, Ives composed at nights and on weekends. Except for within his own head, he rarely heard any of his completed works. He sometimes hired New York Symphony musicians just so he could get an audio glimpse of his creations. His polytonal, polyrhythmic vocabulary baffled them and yet, Ives’ music clearly predicted the directions that composers of the 20th century would take.

His Second Symphony, written from 1897 to 1902, is a five-movement, largely Romantic work. It did not receive its premiere until the New York Philharmonic, led by Leonard Bernstein, performed it in 1951! ((The CSO first played Ives’ Second Symphony in 1959, under conductor Walter Hendl.)

At 44, Ives had a breakdown. He lived on for almost four decades, all those years revising his earlier pieces, but writing no new works after 1926.

In his 60s, he was “discovered” by the musical establishment, and in 1947, his Third Symphony was awarded a Pulitzer Prize. When music’s ultimate outsider was informed of the honor, he announced,“Prizes are for boys — I’m grown up.”

Chicago-based writer Jack Zimmerman has authored a couple of novels, countless newspaper columns and was the 2012 recipient of the Helen Coburn Meier and Tim Meier Arts Achievement Award. He currently works as subscriber relations manager for Lyric Opera of Chicago.

NOTE: The Charles Ives Society has many audio files posted on its site, including samples from the composer’s Symphony No. 2.)

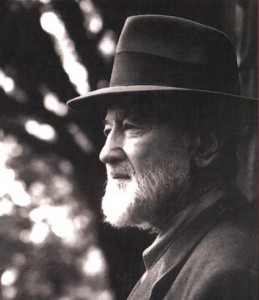

PHOTO: A detail from the U.S. Postal Service stamp honoring Ives, issued in 1997.