Sometimes bigger is better. Anyone who has experienced the roof-raising exhilaration of Mahler’s “Resurrection” Symphony knows exactly the kind of powerful sound that can be created on a stage packed with 100-plus musicians, chorus and vocal soloists.

But sometimes less is more. And that little catchphrase is most emphatically true when the music at hand is a set of solo songs by Franz Schubert. With their beguiling melodies and deep psychological insight, Schubert’s songs can be as compelling as a Mahler symphony or a Wagner opera. With no instrument other than his or her own voice and an accompanying piano, a single artist takes us on an intimate journey that ranges from the most youthful, giddy joy to profound despair.

Schubert will come to Symphony Center audiences in all shapes and sizes this season. The Chicago Symphony Orchestra and Music Director Riccardo Muti are scheduled to perform seven of Schubert’s nine symphonies as well as the Mass in A-Flat Major. But to round out this Schubert survey, the Symphony Center Presents series has lined up three performances devoted solely to the composer’s songs.

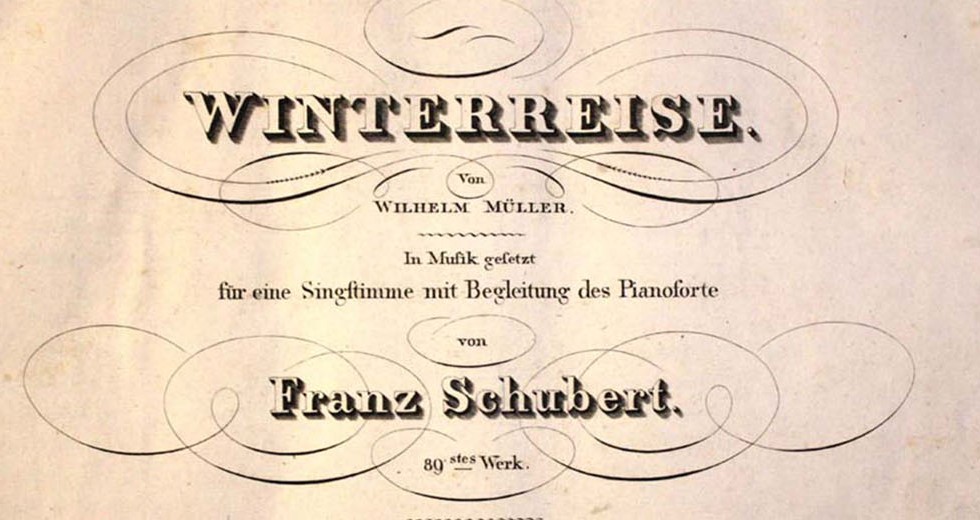

The series was scheduled to kick off Dec. 4 with the Winterreise (“Winter Journey”) song cycle, performed by baritone Christian Gerhaher and pianist Gerold Huber (but the recital was canceled due to illness). It continued Jan. 19 with Die schöne Müllerin (“The Beautiful Maid of the Mill”), performed by baritone Matthias Goerne with Christoph Eschenbach on piano. The series closes May 11 with a joint concert by soprano Susanna Phillips and bass-baritone Eric Owens. They will be joined by members of the CSO in two of Schubert’s more unusual pieces for voice. Phillips will perform Der Hirt auf dem Felsen (“The Shepherd on the Rock”) with John Bruce Yeh, the CSO’s assistant principal clarinet, as soloist. Owens will perform Auf dem Strom (“On the River”) with Daniel Gingrich, CSO acting principal horn.

Born in 1797, Schubert died at age 31. But in that tragically short life, he composed more than 900 works, an astonishing outpouring for any composer, never mind one who died so young. More than 600 of those pieces are songs (often called by the German word for song: lied for a single song, lieder for two or more). Schubert adored poetry and he set to music everything he could get his hands on, from Shakespeare and Goethe to texts by his own poet friends. One of those friends was Wilhelm Muller, whose poems Schubert used in both Die schöne Müllerin (1823) and Winterreise (1827). Typically Schubert’s songs were performed at small gatherings in the homes of his friends or music-loving patrons.

Beethoven is credited with writing the first song cycle or liederkreis: On die ferne Geliebte (“To the Distant Beloved”), a set of six songs written in 1816. Schubert expanded and modified Beethoven’s idea; Schubert’s cycles are chronological stories, tales of lost love that end in despair and death. Often singers will choose a song or two from different cycles to perform on their solo recitals. Two songs from Winterreise — Die Lindenbaum (“The Lime Tree”) and Die Post (“The Mail Coach”) — frequently pop up on solo vocal recitals. But hearing a complete song cycle is a very different experience. Each song unfolds like a chapter in an engrossing novel. Like hearing Bach’s Goldberg Variations or all six Bartok string quartets, the chance to hear the complete Winterreise or Die schöne Müllerin is an experience that music lovers prize.

A set of 20 songs, Die schöne Müllerin opens with a happy young man traveling the countryside, buoyed by the streams and flowers that surround him. He encounters the pretty daughter of a miller but soon realizes he is no match for her other suitor, a dashing huntsman. He drowns himself in the brook that once made him so happy and the flowers he admired become decorations for his grave.

Written four years later when Schubert was close to death himself, the 24 songs of Winterreise have a similar narrative arc but their atmosphere is much more weighty. The young suitor is more cynical, certain that his beloved has spurned him for a rich man. Wandering away from her town, he stumbles through a mostly dark landscape. Winter storms rage and he finds himself at a cemetery. He sees a ghostly hurdy-gurdy man who seems to be summoning him to death.

Throughout both cycles, the piano helps establish the mood, whether burbling like a lively brook or relentlessly repeating the slow, ominous little tune of frightening hurdy-gurdy man. Schubert’s melodies are so rich that singers can perform these cycles throughout their careers. A young singer may bristle with rage at Schubert’s fickle young women, and we share his anger. But older singers bring something equally powerful to the songs, an awareness that tragic loss is both inevitable and universal. Both Die schöne Müllerin and Winterreise offer nothing less than a meditation on the human condition.

Over the years, distinguished singers have performed Schubert’s songs on Symphony Center’s main stage. With approximately 2,500 seats, it also accommodates chamber music and solo recitals. But for these Schubert concerts, Symphony Center staff is aiming for something even more intimate.

The goal is to make approximately 700 seats available, the vast majority of them in the center section of the main floor and at the box level. There will be 40-some seats onstage. Those will be arranged in three rows on either side of the piano with listeners facing the artists. Onstage ticket holders will have assigned seats rather than operating on the more typical first-come, first-served basis.

“The aim of this is bring the artist and the audience as close as possible in an already intimate space,” said James M. Fahey, director of programming for Symphony Center Presents. “The space that these songs were originally performed in was very small. So it was a combination of only selling the front portion of the main floor, front to back, then using the boxes. I want this to be a unique experience for the patrons.”

Wynne Delacoma, formerly the classical music critic for the Chicago Sun-Times, is a freelance writer and reviewer.

PHOTO: First-edition folio in of Schubert’s Winterreise.