Common wisdom has it that writing a 10th symphony is the compositional equivalent of breaking a mirror while walking under a ladder. The “Curse of the Ninth” remains embedded in popular culture and journalistic shorthand, and much of its perpetuation is due to the famously superstitious, devout numerologist Arnold Schoenberg. specifically in reference to Gustav Mahler, Schoenberg waxed paranoid when discussing the otherworldly significance of the number nine when it came to symphonists: “It seems that the Ninth is a limit. He who wants to go beyond it must pass away. It seems as if something might be imparted to us in the Tenth which we ought not yet to know, for which we are not ready. Those who have written a Ninth stood too close to the hereafter.”

Got that, composers? Nine is a rubicon; cross it and die.

It’s a fascinating theory. Complete hogwash, but fascinating.

Error, oversimplification and an embarrassingly large cultural blind spot have led us to this point. For every Schubert or Bruckner who died after completing nine symphonies (a questionable statement itself, requiring a lot of musicological fudging), there is a Villa-Lobos (11), or Milhaud (12) who did not. Shostakovich completed 15 symphonies. Apparently he went six levels beyond the hereafter, and apparently we were ready for it. Good for us.

Still, in reference to Mahler, it’s easy to understand what prompted Schoenberg to make the statement, despite its boogety-boogety undertone. The year 1908 was traumatic for Mahler, and intimations of mortality surrounded him while writing what came to be his final completed work. He’d lost his position as director of the Vienna Opera, had been diagnosed with endocarditis and was grieving the death of his 4-year-old daughter.

While he proclaimed himself in good health during this time, the work is permeated by reflections on death: his lifelong fear of it and an intensified love of life. The first movement’s main theme draws from Johann Strauss’ Freut euch des Lebens (“Enjoy Life”) and makes allusions to Beethoven’s Les Adieux (“Farewell”) sonata. The work’s final note is marked ersterbend (“dying away”). The theme can hardly be more explicit. In fact, Leonard Bernstein heard no less than three “deaths” in the piece:

“Mahler’s Ninth [poses] a great question; but it’s more: it contains a deeply revealing answer … the most startling answer, the most important one – because it illuminates our whole century from then to now – is this: That ours is the century of death, and Mahler is its musical prophet. What was it that Mahler saw? Three kinds of death. First, his own imminent death of which he was acutely aware. (The opening bars of this Ninth Symphony are an imitation of the arrhythmia of his failing heartbeat.) And second, the death of tonality, which for him meant the death of music itself, music as he knew it and loved it. And finally, the death of society, of our Faustian culture. The fourth and last movement [is] the final farewell. It takes the form of a prayer, Mahler’s last chorale, his closing hymn, so to speak; and it prays for the restoration of life, or of tonality, of faith. But there are no solutions.”

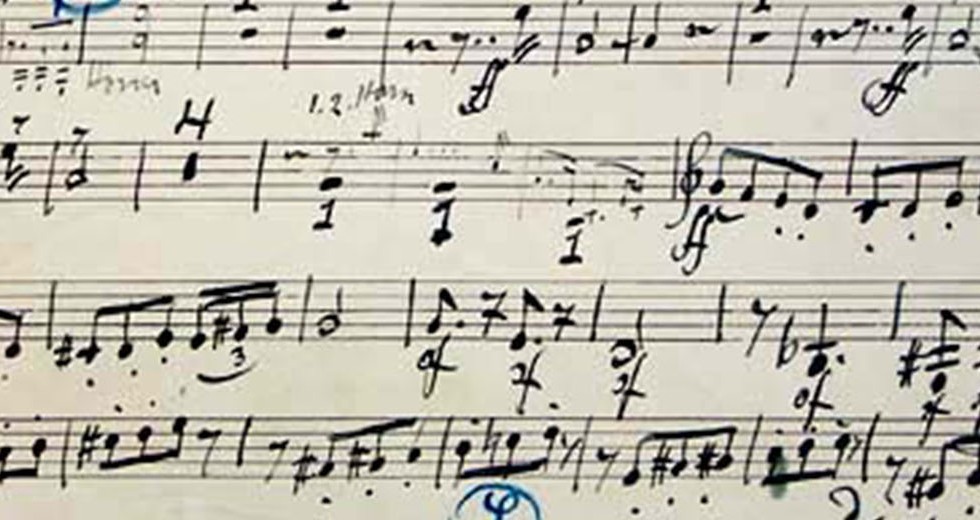

But as tempting as it is to read the work as a valedictory, there is no hard evidence that Mahler believed it was such, and in fact, the final years of his life found him enjoying great success and productivity. Having finished the ninth symphony in Europe in 1909, he returned to New York to lead an active season with the New York Philharmonic (46 performances in 1909-1910) and was planning an extensive tour with the orchestra for 1910-1911. The premiere of his eighth symphony, in September 1910, was, according to biographer Robert Carr, “easily Mahler’s biggest lifetime success.” He was busily composing and left a substantial draft of his 10th symphony when he died at age 50 in May 1911.

This is not to say Mahler himself wasn’t aware of “The Curse.” More than 80 years had passed since Beethoven died (Exhibit A for “The Curse” adherents), and in that time, no major composer had crossed the forbidden threshold. Perhaps it was a bit of latent superstition that drove Mahler to compose the eminently symphonic “Das Lied von der Erde,” yet refuse to number it with his symphonies. In separating out the work from his symphonic canon, he made his own “Appointment in Samarra.” Maybe he believed he cheated fate, but he died without ever hearing the ninth performed, and we are left with nine numbered and completed symphonies; more grist for the superstitious among us.

Peter Lefevre writes about music for the Orange County Register and Opera News.