For listeners unfamiliar with the works of Sergei Prokofiev, Dmitri Shostakovich and Igor Stravinsky, they might expect to hear significant similarities among their compositions.

All three were Russian, born with 24 years of one another, and shared certain common influences (for example, Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov taught Prokofiev and Stravinsky). In addition, the lives of all three were affected directly or indirectly by the Russian Revolution of 1917 and the brutal reign of Soviet leader Joseph Stalin, not to mention the devastation of two world wars.

But the differences among these three composers’ works far outweigh their similarities, as demonstrated by their respective violin concertos, which will be performed during the 2013-14 season at Symphony Center.

“They are so close and yet so far apart,” said violinist Leila Josefowicz, the soloist for the Chicago Symphony Orchestra’s performances Oct. 17, 19 and 22 of Stravinsky’s Violin Concerto.

Stravinsky (1882-1971), the best known and the most influential of the three composers, spent virtually his entire life outside Russia, changing the entire course of modern music first with his revolutionary ballets, especially The Rite of Spring, in 1913.

Stravinsky (1882-1971), the best known and the most influential of the three composers, spent virtually his entire life outside Russia, changing the entire course of modern music first with his revolutionary ballets, especially The Rite of Spring, in 1913.

“Stravinsky made an astronomical career in the West – absolutely spectacular,” said Victor Yampolsky, a Russian-born violinist and conductor who is director of orchestras at Northwestern University’s Bienen School of Music.

With references to J.S. Bach and Baroque musical structures, Stravinsky’s elegant, witty concerto is written in the composer’s neo-classical style, which began in the 1920s with his ballet, Pulcinella. “I think you could say that it is a Baroque concerto, which is being spiced up by the modern discoveries of harmonies and rhythms and the interesting sounds of the 20th century,” he said.

Like Stravinsky, Prokofiev (1891-1953) left Russia during the revolution, but in the ’30s, he began to long for his homeland and decided to return in 1936. Although the composer wrote some of his most significant works subsequently, like his Symphony No. 5, he ran afoul of a cultural crackdown after World War II; his wife, Lina, was imprisoned for “espionage” in 1948.

“Shostakovich was a totally Soviet composer,” Yampolsky said. “Prokofiev was a Russian composer who became an implant in his own country, and finally became incarcerated in his country. His spirit, his creativity – he became a slave, like most of the Soviet composers.”

Prokofiev’s Violin Concerto No. 2 was written a year before left Paris for Russia, and it exhibits a shift toward a “new accessibility,” a desire to make his works more palatable to Soviet tastes, said Peter Schmelz, associate professor of musicology at Washington University in St. Louis.

The work, which the St. Petersburg Philharmonic will perform Feb. 23 at Symphony Center, can be seen as following in the lineage of the earlier romantic violin concertos of Russian composers such as Alexander Glazunov and Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky. It contains strong hits of his popular ballet, Romeo and Juliet, which he completed in 1938.

Because he remained in the Soviet Union for his entire career, Shostakovich was constantly subjected to the edicts of its oppressive government. In 1936, his opera, Lady Macbeth of the Mtsensk District, was denounced, and he faced the risk of imprisonment and even death.

“I think Shostakovich had the most emotional struggle of the three, with the Soviet regime and the rules and not being allowed to write so much of what was in his head,” said Josefowicz, who has recorded his Violin Concerto No. 1, which guest soloist James Ehnes performed Dec. 5 and 7 with the CSO.

Indeed, as Schmelz points out, this work was written just after World War II, but Shostakovich kept it under wraps for his own protection and did not turn it over to his publisher until 1955, two years after the death of Stalin. “It was written around 1947-’48, when the government was cracking down on music and the other arts in a pretty severe way,” said Schmelz, author of Such Freedom, If Only Musical: Unofficial Soviet Music During the Thaw.

Shostakovich’s struggles and those of his fellow citizens can be heard in this sometimes grim, even violent work, which contrasts sharply with the lightheartedness and romance of the two concertos by Stravinsky and Prokofiev.

“The depth of this music is unsurpassable,” Yampolsky said. “The questions which he asks in this music have nothing do with the Baroque or the Ballets Russes. They have something to do with the fate of Russian people, with unfairness, with the combination of a terrible, despotic totalitarian regime and a devastating war. So, for me, it is music from a completely different planet.”

Kyle MacMillan is a Chicago-based writer and reviewer.

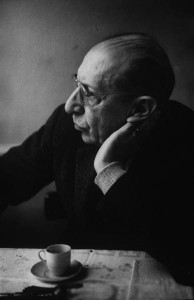

PHOTOS: Sergei Prokofiev (left) and Dmitri Shostakovich in the mid-1930s. INSET: Igor Stravinsky.

VIDEO: James Ehnes discusses Shostakovich’s Violin Concerto No. 1, which he will perform Dec. 5 and 7 with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. Video via YouTube from the Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra of England.