Just a cursory look at the commentaries on Mahler’s Symphony No. 7 in E Minor, and one has the immediate impression that its critics resemble the six blind men examining an elephant: Everyone is very confident, and no one agrees with anyone else.

Granted, Mahler is one of the most polarizing of composers. His rightful place in the canon, the influence, meaning and purpose of his work, what exactly he was trying to say in any given piece — so much is up for detailed and animated debate.

These discussions usually take place within fairly defined boundaries. There are at least some points of consensus. When it comes to the Seventh (which the CSO will perform April 9-14 under Bernard Haitink), though, it’s nearly a free-for-all.

Is it echt Mahler? Is it, as Frank Berger (author of Gustav Mahler: Vision and Mythos) considers it to be, the composer’s most representative piece?

“Absence of context and disintegration of form are two of the main characteristics of Mahler’s work,” he says, “and are surely his great strengths. The Seventh Symphony is the work in which these characteristics are in clearest evidence, and it is for this reason that the symphony may surely be regarded as one of the most quintessentially Mahlerian of works.”

Thank you, Mr. Berger. Now, if we may call a rebuttal witness to the stand. Deryck Cooke, one of the greatest of Mahler’s champions, considers the finale of the Seventh to be a case of Mahler writing the kind of music that he himself detested, “Kappelmeistermusik,” music of uninspired correctness. Vast is the crowd that hears this as the most un-Mahler-like of his symphonies.

Yet Arnold Schoenberg, certainly not a proliferator nor fan of uninspired correctness, was famously “converted” into a Mahlerian by the Seventh. He showered Mahler with praise after hearing the work’s premiere on Sept. 19, 1908.

“As for which movement I liked best: All of them!” said the not normally effusive man, who was soon to unleash Erwartung on the world. “From minute to minute I felt happier and warmer. And it did not let go of me for a single moment. In the mood right to the end. And everything struck me as pellucid. Finally, at the first hearing I perceived so many formal subtleties, while always able to follow a main line. It was an extraordinarily great treat.”

Adding to the voices in favor of the work’s daring nature is Donald Mitchell, whose extensive writings on Mahler includes this commentary: “Today, at the beginning of the 21st century, it has become virtually received opinion that the Seventh represents Mahler at his most ‘modern,’ as one of the prime makers of the ‘new’ music that was to startle the world post-1900.”

So let’s have a look at the scorecard so far: the Seventh is Mahler’s most and least characteristic symphony; highly conservative, and radical enough to win over one of music’s most notorious rebels.

Hmm.

Searching for meaning within a programmatic context leads to slightly greater clarity if only because we have some limited guidance from the composer himself. The first two movements he composed are marked “Night Music,” and he wrote a nightmarish scherzo (marked with the directive “Shattenhaft” [“shadowy”]) that separates them. Mahler compared the first of these movements to Rembrandt’s “The Night Watch”; as historically reluctant as Mahler was to providing programmatic meaning to his work, he described the symphony’s plan to Swiss critic William Ritter this way: “Three night pieces; the finale, bright day. As a foundation for the whole, the first movement.” Simple enough, although Mahler denied wanting to literally depict “Night Watch” and rejected the title of “Song of the Night,” the nickname by which the work is sometimes known.

Still, we can use the general theme of “night” as a skeleton key, and place the work on a reasonable point in Mahler’s development.

The work is filled with shadows and contrasts: “chiaroscuro” is a description that frequently emerges in analysis of the work. This dovetails brilliantly with Mahler’s stated inspiration for the “Night Watch” movement: Janus-faced, marked by the play of light and dark, clarity offset by obscurity, a wealth of contrary impulses.

We can find these contrasts everywhere: in the extreme instrumental ranges and orchestral textures; the comforting reassurance of symmetrical design against the disorienting tempi shifts; the mystery of the dreamscapes set against the fanfares and heraldry of the finale.

With that much of a muchness, it’s not surprising that astute listeners can come to such widely different conclusions. We all experience our own nights in our own subjective ways; some as nightmares, some as moonlit evenings.

Mahler came to this work following the desolation of the Sixth, lending credence to the argument that this work functions therapeutically. Perhaps he rejected calling it “The Song of the Night” because he knew that day would follow. He himself considered the finale some of his most affirming and joyful music, written even in the midst of personal tragedy (the death of his oldest daughter, the confirmation of his untreatable heart condition). Those who would hear a thread of insincerity in the conclusion, simply aren’t taking the composer at his word. “The emotional grief is overcome, the triumph is real,” Berger says about the finale. Or, as Mahler describes its meaning: “The world is mine!”

Based in California, Peter Lefevre writes about classical music for the Orange County Register and Opera News.

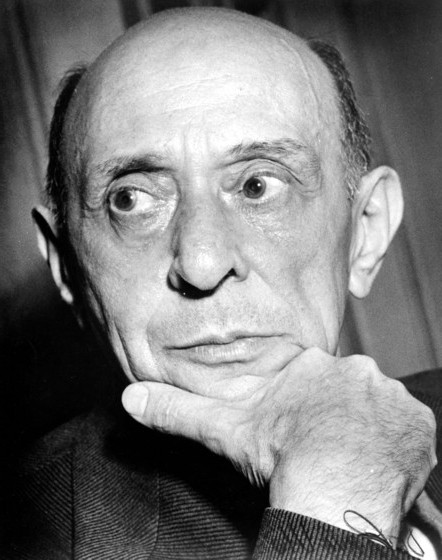

TOP: Detail from a 1907 portrait of Gustav Mahler, by Aksel Gallen Kallela.