I can remember being in college and listening to Mahler’s Ninth Symphony with fellow students. At that time none of us knew much about life or music. But hearing those sounds of Mahler’s gave us the sense that we had tapped into something grand and universal, something deeply profound and far beyond the world we had known. The Mahler Ninth still does that to me.

A few years back as the world prepared for the new millennium, I informally polled musicians about their choice for the greatest composer of the 20th century. Not surprisingly, most string quartet musicians chose Bartok (those six quartets are hard to beat), academics went for Stravinsky and Schoenberg, and orchestra players enthusiastically endorsed Mahler.

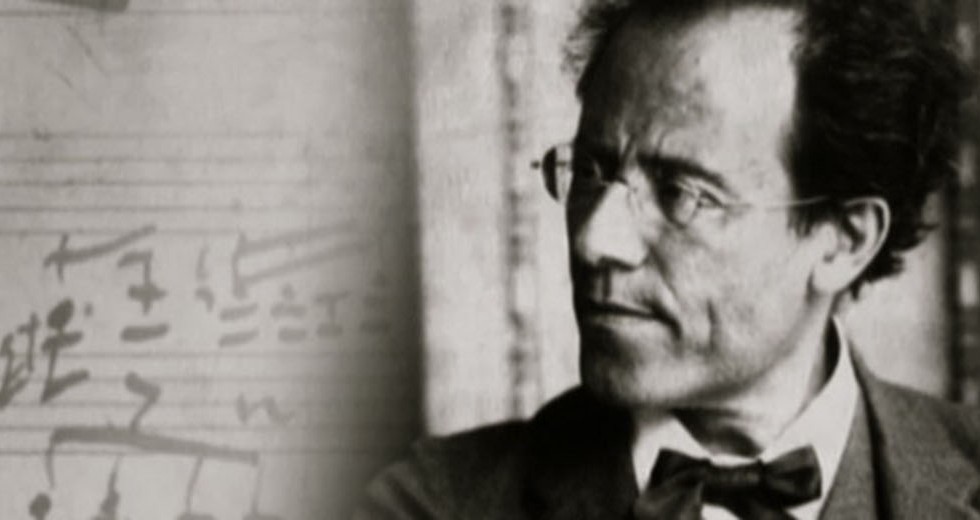

Of course they would! Mahler, more than any other composer, understood the orchestra and focused his creative energies in writing for it. It’s easy to forget that Mahler composed only in the summer months. He conducted the rest of the year. “Mahler was the greatest performing musician I ever met, without any exception,” the legendary conductor Bruno Walter once insisted.

Mahler lived only a single decade in the 20th-century, and his music clearly speaks the language of 19th-century romanticism. But his symphonies transcend historical periods. They appeal to us in the 21st century because they are so unabashedly ambitious. His sprawling canvases portray the sum of human experience: abandonment, despair, joy and redemption — “the whole world,” as the composer often said.

His Ninth was the last symphony he completed. He finished it in 1909 and died in May 1911. The work premiered in Vienna in June 1912, conducted by Bruno Walter. The Ninth Symphony requires fewer forces than some of the others – no mammoth chorus or even a children’s choir and no solo singers. The work is contained in four movements: andante comodo; a charming ländler that soon runs off the rails, no longer resembling anything danceable; a rondo-burleske, and an adagio that’s marked “very slowly and held back.” The adagio movement is often viewed as Mahler’s goodbye to the world, and indeed, that’s what it is.

Chicago-based writer Jack Zimmerman has authored a couple of novels, countless newspaper columns and was the 2012 recipient of the Helen Coburn Meier and Tim Meier Arts Achievement Award. He currently works as subscriber relations manager for Lyric Opera of Chicago.