On the night of June 16, 1816, a group of writers — including Lord Byron, Percy Bysshe Shelley, Mary Wollstonecraft (soon after to marry Shelley), Claire Clairmont and John William Polidori — listened to stories aloud by Lord Byron, after which Byron suggested that each member of the group try to write a ghost story. Although Percy Shelley and Claire Clairmont lost interest in the contest, Byron himself wrote “The Vampyre”— itself a precursor to Bram Stoker’s Dracula — and Polidori wrote a now-forgotten, untitled story about a skull-headed lady punished for peeping through a keyhole. Meanwhile, Wollstonecraft wrote one of the most famous novels of all time, Frankenstein, or The Modern Prometheus.

Even with Mary’s famous literary husband pushing for publication of Frankenstein, no conventional publisher was willing to take the risk of releasing such a shocking tale of a scientist daring to create an artificial man, only to have it turn on him. By the time the novel finally appeared in 1818, response was immediate and overwhelming, and it quickly became one of the biggest best-selling books of the 19th century. Frankenstein so fascinated the public that within Mary Shelley’s own lifetime, there were no less than three stage adaptions. Unlike the novel, the stage plays concentrated exclusively on the story’s horrific nature, with the unnamed monster taking centerstage. (Even then, audiences began confusing the creature with the name of its creator, a practice which continues to this day.)

Sara Karloff, daughter of the horror icon, has made it her life’s work to preserve her father’s legacy.

Stage versions of Frankenstein continued to abound throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries, and no sooner had Thomas Edison invented the movie projector before the first film version of the story was made, at Edison’s own studio in 1910. Although another silent version called “Life Without Soul” appeared in 1920, Universal Pictures, 11 years later, made the cinematic version of “Frankenstein” that is still the standard by which all others are measured.

Having scored a spectacular triumph in “Dracula” (1931), the studio immediately acquired the rights to film “Frankenstein” as a follow-up, basing its script on the Peggy Webling 1927 version of the play. Director James Whale then “found” a 44-year-old bit player on the lot named William Henry Pratt, who went by the stage name of Boris Karloff. Whale had noticed Karloff eating his lunch in the studio commissary and began making sketches of his face. (The Chicago Symphony Orchestra will present a live-to-picture performance of “Bride of Frankenstein” at 7:30 p.m. Oct. 26, conducted by Emil de Cou, followed by a bonus screening of Mel Brooks’ “Young Frankenstein.”)

“To put it in perspective, ‘Frankenstein’ was my dad’s 81st film,” said Sara Karloff, daughter of the horror icon (and who will introduce screenings of “Bride of Frankenstein” at 2 p.m. and 7:30 p.m. on Oct. 18 at the Pickwick Theatre in Park Ridge.) “He made 167 films in total, so nearly half of his career was spent in total obscurity. He had served his time and had learned his craft in repertory theaters in British Columbia and then in the States, eventually making his way to Hollywood, where he was a extra in silent films for years and years. Finally, Dad got some bit parts, but did everything under the sun, from shoveling coal to driving a truck to keep from starving to death while waiting for the next call.”

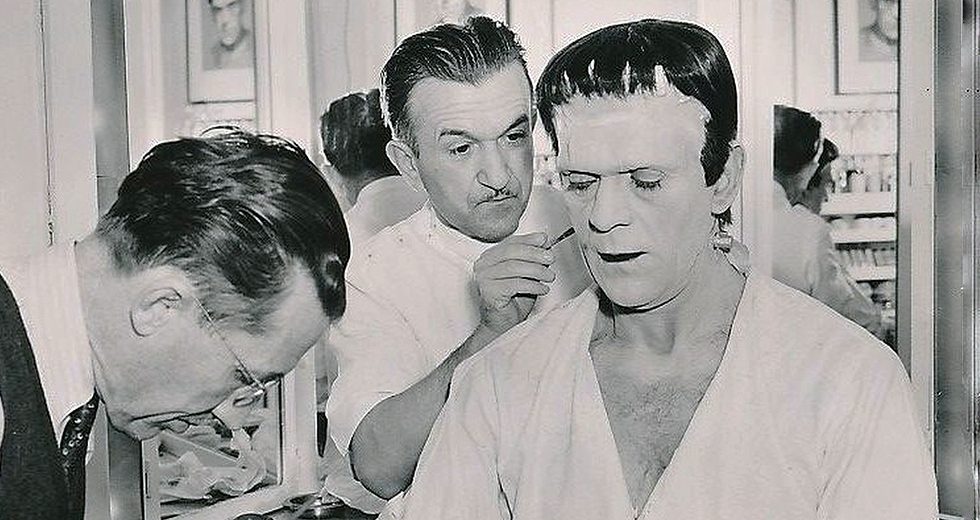

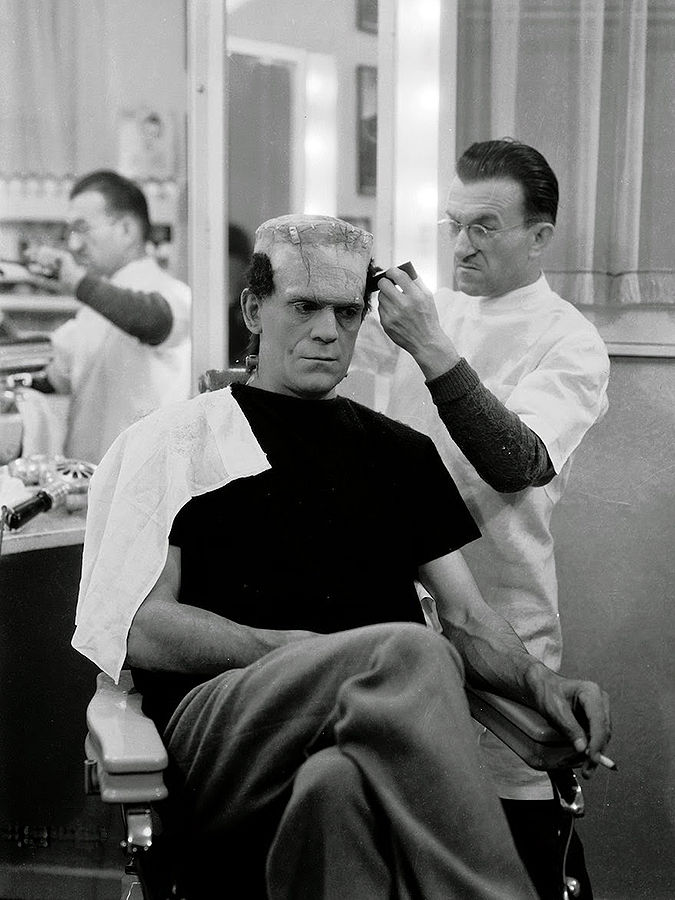

Karloff was delighted at the attention from such a major director as Whale, and agreed to let Universal’s chief makeup artist and former semi-pro Chicago shortstop Jack P. Pierce to experiment with him at will. Karloff even came up with the idea of allowing Pierce to remove a dental bridge to give one side of the monster’s face a more sunken look. Three intensive weeks followed where Pierce experimented with various effects to transform the thin Englishman into a monster made from pieces of dead bodies.

Pierce did an extraordinary amount of homework in anatomy, surgery, medicine, criminology, burial customs and electrodynamics to create his startling makeup, which reportedly took six hours to apply initially. That makeup design has become such a familiar icon of pop culture that it is virtually impossible nowadays to imagine how truly horrified audiences were when they first saw Karloff as the monster on screen in 1931. Suspense had been further heightened by Karloff’s initial appearance coming nearly a half hour into the film, fed by the film’s unprecedented onscreen prologue with an audience warning and opening credits with simply a question mark where Karloff’s name should have been. “Frankenstein” was shot on a closed set for three months; Karloff was led from the makeup department with his head completely covered after an incident where a pregnant studio secretary had caught sight of him and fainted. Soon moviegoers would react the same way. “My father would always say that it was thanks to the genius of Jack Pierce and his makeup that the monster became what it became,” his daughter said.

Chicago native Jack Pierce devised the makeup design for Karloff’s Monster.

Yet there’s no denying that despite Pierce’s amazing makeup, which, having been conceived around Karloff’s features, was never as convincing on the later actors who portrayed the monster in the Universal sequels. It was Karloff’s pantomime acting through the makeup that made his performance so memorable. Karloff saw the monster as a lost child and was able to convey that sense even through such heavy layers of makeup. “Children were not afraid of the monster and would come up to my father all the time and voice the opinion that the monster was the victim and not the perpetrator,” she said.

Yet Karloff was considered so insignificant when the film was released, that aside from not being credited until the film’s end, he was not even invited to the movie’s premiere. “My mother mother and father went up to visit a college friend of hers up in the Bay Area,” Sara Karloff recalled. “ ‘Frankenstein’ happened to be playing up there, and the shooting days had been so long with the hours of added makeup application and removal that my father couldn’t see the daily rushes so had never seen the film in its entirety. The scene comes along where the monster turns around in the doorway, and my mother’s friend said to my mother — whose name was Dorothy but she was known as Dot — ‘Oh, Dot! How could you possibly live with such a monster!’ Of course, they were ushered out of the theater!”

Such anonymity quickly became a thing of the past for Karloff. Indeed, after “Frankenstein,” the actor would receive a rare honor in cinema, accorded to only the likes of a Chaplin or a Garbo: He would be billed simply by his last name. Plans were immediately made for a much more elaborate sequel to the film called “The Return of Frankenstein,” which would later be renamed “Bride of Frankenstein.” James Whale would again direct, Karloff would reprise his role as the Monster, this time reeiving the lead credit as simply “Karloff.” Colin Clive, the British actor who had played Henry Frankenstein in the original and who was actually considered the “star,” until the studio realized that the public was far more interested in the Monster, was also back.

“It is one of the rare instances of a sequel that is often considered to be better than the original,” she said. “My father objected to the monster speaking in the film, but cinema history has proved him wrong. It is so irreverent and comical. Ernest Thesinger is so evil and hysterical, he practically steals the film. The music has legs of its own. I wish I could be in Chicago to hear the wonderful score played live by the Chicago Symphony, but just like my father, Halloween is my busy season.”

However, she will be in the area to the week before introduce screenings of “Bride of Frankenstein” where she will show family home movies and interviews with her father, discuss her father’s career and take audience questions. “I am nothing but a conduit,” she said. “They get a chance to ask questions that they wish to goodness they had a chance to ask my father.”

On whether Karloff regretted being stereotyped as a “monster” and a “horror star, his daughter insists “heavens no. He always said that ‘a typecast actor is a working actor,’ and how jolly lucky of a fellow he was to be typecast so that his name and face came to mind when a certain kind of role came up, which kept him working all of his life.”

Boris Karloff beams at his daughter, Sara, his only child. | Photo courtesy of Sara Karloff

Karloff, however, was nothing like his sinister screen persona in his private life. “His passions were cricket, gardening and reading,” she said. “He was educated in English schools and was very cultured and well-read, the antithesis of the roles that he played. He was soft-spoken and modest, gentle and generous, and truly concerned with the plight of his fellow actors. One of my father’s proudest accomplishments was to have helped form the Screen Actors Guild, which was a very dangerous thing to do at that time. But having struggled for so many years before his success, it was a cause very dear to his heart. He served on the board for 35 years.”

Karloff was able to parlay his stardom in the horror film genre into other successful show business endeavors; he had enormous success starring on Broadway in “Arsenic and Old Lace” in a role that was written for him and was nominated for a Tony Award for his role as a cardinal persecuting Julie Harris’ Joan of Arc in “The Lark.” He sang the role of Captain Hook in Leonard Bernstein’s Broadway musical adaption of “Peter Pan” and frequently read children’s stories on the radio and on records as “Uncle Boris.”

One of the first major film stars to embrace television in its infancy, Karloff loved the challenge and variety of live acting in non-horror roles such as Joseph Conrad’s “The Heart of Darkness” alongside Roddy McDowall, and also went on to host the “Thriller” television series. Karloff even won a Grammy Award for the soundtrack album to his narration for the 1966 animated television special “Dr. Seuss’ ‘How the Grinch Stole Christmas!’,” which remains a holiday staple to this day. “It’s the one time [he told me], ‘I’ve done this thing and I think it’s pretty good. If you can, maybe you and the boys could sit down and watch it.’ And that was the Grinch. He never talked about his work, but was thinking about his grandchildren. They loved it. They still do!”

In addition to such diversification, Karloff was always able to poke fun at his own “boogie man” image in films such as “Comedy of Terrors” and the remake of “The Raven,” as well as on TV cameos such as his famous 1962 appearance on a “Route 66” Halloween episode filmed near O’Hare Airport, with Peter Lorre and Lon Chaney Jr. Karloff one again donned the makeup of Frankenstein — the character Karloff referred to as “my best friend,” recognizing that without it, he would never have become the household name he became — for the last time. Karloff was also a stock voice characterization for comedic impressionists, and imitations of his voice have been used for everything from selling breakfast cereals to hit records such as Bobby “Boris” Pickett’s 1962 rendition of the “Monster Mash.”

One of Karloff’s best films, according to his daughter, was one of his last, where he played an aging, introspective horror star in Peter Bogdanovich’s “Targets” (1968). “He essentially was playing himself. It is a remarkable performance.” Though Karloff had emphysema in his last years, he kept working. He died in England on Feb. 2, 1969. “I just came back from the U.K., where I was invited to speak for the Frankenstein bicentennial nearly half a century after Dad had passed away. Thanks to people being able to see so much of his work and it holding up, his legacy remains.”

Award-winning veteran journalist, critic, author, broadcaster and educator Dennis Polkow has described himself as “a Monster Kid” for over half a century.