The Chicago Symphony Orchestra presented the world-premiere “live” performance of Franz Waxman’s score to James Whale’s “Bride of Frankenstein” (1935) during Halloween week in 2008 under Richard Kaufman, with Waxman’s son, John, in attendance. This season’s live-to-picture performance on Oct. 26 of “Bride” by the CSO will be conducted by Emil de Cou and also will include a bonus screening of Mel Brooks’ “Young Frankenstein” (1974).

On a cloudy Memorial Day in 1957, James Whale was found lying face down at the bottom of the swimming pool of his Pacific Palisades home. In a scene as meticulously crafted as any the fastidious 67-year-old British director filmed, Whale was immaculately dressed in his best blue suit and had left a copy of the novel Don’t Go Near the Water by his bedside in a last bit of gallows humor.

A hand-written two-page suicide note was addressed “To ALL I LOVE,” and carefully explained that while he had a “wonderful life” behind him, his “nerves were shot” and he was “in agony day and night” except when he was heavily medicated and that “the future is just old age and illness and pain.” Asking forgiveness and leaving assurances that his financial affairs were in order, which he hoped would “help my loved ones to forget a little,” Whale asked that he be cremated so that “no one will grieve over my grave.”

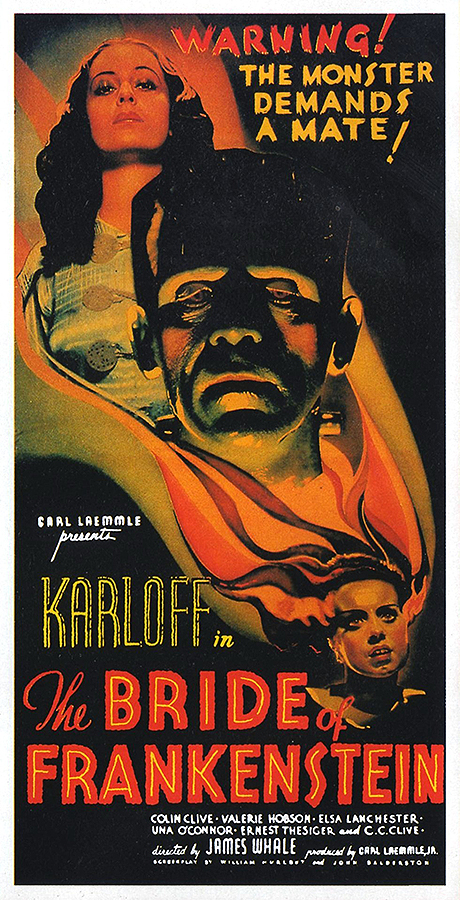

Sadly, Whale never lived to see the renewed interest in his films that would result from “Frankenstein” (1931) and “Bride of Frankenstein” being sold to television less than a year after his suicide. The fascination with these films helped spawn a Baby Boomer pop culture phenomenon: the creation of monster magazines, monster models, trading cards, board games, sweatshirts and the like mere months after Whale’s watery plunge.

Sadly, Whale never lived to see the renewed interest in his films that would result from “Frankenstein” (1931) and “Bride of Frankenstein” being sold to television less than a year after his suicide. The fascination with these films helped spawn a Baby Boomer pop culture phenomenon: the creation of monster magazines, monster models, trading cards, board games, sweatshirts and the like mere months after Whale’s watery plunge.

“What is astonishing about James Whale was the way that he virtually created the modern horror film genre out of thin air,” said James Curtis, author of the biography James Whale: A New World of Gods and Monsters (1998; updated, 2003). “Lon Chaney had played a series of grotesque and deformed characters during the silent era who were often sympathetic, but none of them were truly supernatural. Bela Lugosi’s ‘Dracula’ was supernatural, but there was nothing sympathetic about the character. With Whale, for the first time, you have a monster in ‘Frankenstein’ who was supernatural and sympathetic.”

In addition to “Frankenstein” and its far more elaborate sequel, “Bride of Frankenstein,” Whale also directed “The Old Dark House” (1932) and “The Invisible Man.” So powerful were those films that although these were the only “horror” films Whale ever made and represent only a fraction of his filmography, he would be indelibly associated with the genre as a result.

Actress Gloria Stuart, who died in 2010 at the age of 100, was the leading lady in “The Old Dark House” and “The Invisible Man” as well as Whale’s “The Kiss Before the Mirror.” After director James Cameron heard Stuart’s lively, improvised commentary on a 1995 restoration release of “The Old Dark House” on laser disc, he cast her as Old Rose in “Titanic” (1997); Stuart received an Oscar nomination for her role in Cameron’s blockbuster.

“I adored him,” Stuart told me of Whale in 1997. “He was a real actor’s director. I worked twice with [director] John Ford, and there was no comparison. Ford would just say, ‘action,’ and left you on your own. With James, everything you were to do had been carefully thought through and worked out in the most minute detail. He was a ‘hands-on’ director in that he was into every aspect of the picture: makeup, costumes, scenery, lighting, props: everything. He was always meticulous, discerning and helpful.”

When Whale did the original “Frankenstein” in 1931, “talkies” were still a novelty and were treated much like stage plays with the attention on spoken dialogue. While musical accompaniment had fulfilled a constant narrative role in silent films, early sound films went largely without music during talking scenes so dialogue could be heard. When “Frankenstein” became a blockbuster and a larger budget was possible for a much more epic sequel, Whale knew that he wanted music to be a primary element. Rather than be used merely for credits and a few transitions, Whale envisaged a sweeping score setting the tone of each scene, and swelling and pulling back alongside action and dialogue. It became one of the earliest templates for a virtually through-composed Hollywood “soundtrack” in the contemporary sense still in use today.

In 1934, at a weekly Sunday salon hosted by writer Salka Viertel for Hollywood European refugees, Whale met German composer Franz Waxman (1906-1967), who had orchestrated and conducted Frederick Hollander’s score for Josef von Sternberg’s classic “The Blue Angel” (1930), which introduced Marlene Dietrich to American audiences. As a result, Waxman was hired to compose a score for Fritz Lang’s film version of “Liliom” (Lang had already left Germany as the Nazis came to power), which led to Waxman’s invitation to Hollywood to arrange the Jerome Kern score for “Music in the Air” (1934).

Franz Waxman wrote a lush and often whimsical score for “Bride of Frankenstein,” and his music was a vital component of the film’s success.

Whale admired Waxman’s score for “Liliom” (1934) and offered him the opportunity to score “Bride of Frankenstein.” Waxman’s lush and often whimsical music was a vital component of the success of that film; it was recycled endlessly in other Universal films, Westerns and serials, including Buster Crabbe’s “Flash Gordon.”

The success of that score alone led to Waxman’s appointment as head of the music department at Universal, a position he happily accepted with Hitler in charge back in his homeland. At Universal, Waxman composed music for more than a dozen films in two years before moving to MGM, where he scored Spencer Tracy films such as “Captains Courageous,” “Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde” and “Woman of the Year” before landing at Warner Bros. (there, Waxman wrote his Oscar-winning and most famous scores, “Sunset Boulevard” [1950] and “A Place in the Sun” [1951]).

Although Waxman scored nearly 150 films across a more than three-decade career, he never lost his appetite for non-commercial music and in 1947 founded the Los Angeles International Music Festival, which he ran for 20 years until his death in 1967. Under Waxman’s direction, that festival had presented the West Coast premieres of more than 70 works, including those of Bernstein (Symphony No.2, The Age of Anxiety, 1951), Britten (War Requiem, 1964), Foss, Harris, Honegger, Mahler (Symphonies Nos. 3, 9 and a reconstruction of 10), Mennin, Orff, Piston, Poulenc, Schoenberg, Shostakovich (Second Piano Concerto, Symphonies Nos. 4 and 11), Stravinsky (Oedipus Rex, 1954; Agon, world premiere, and Canticum Sacrum, U.S. premiere, both 1957), Vaughan Williams and Walton, among others.

Waxman’s own Carmen Fantasy, based on themes from Bizet’s Carmen that he originally wrote for the film “Humoresque” (1946) and which Isaac Stern recorded for the soundtrack, became a best-selling recording and remains one of Waxman’s standard repertoire pieces. (A world premiere recording of Waxman’s 1959 oratorio Joshua has been released on Deutsche Grammophon.)

Waxman, along with Viennese-born Erich Wolfgang Korngold (1897-1957) and Max Steiner (1888-1971) and Hungarian Miklós Rózsa (1907-1995), are together remembered as promising young European émigré composers who, in fleeing Nazism, created the soundtrack for the golden age of Hollywood.

Five-time Ocsar-winning and 23-time Grammy Award-winning American composer-conductor John Williams, the longest-reigning and most successful film composer still working in the same Hollywood symphonic tradition, began his career in the late 1950s working as pianist, arranger and orchestrator for — who else? — Franz Waxman.

“When you’re scoring a scene from a movie, which, say, may be seven minutes long,” Williams told me in 1992 in describing a scoring process that has remained largely unchanged since his days with Waxman, “you do a timing breakdown and study those seven minutes for structure so you see where the loudest point of the music will come, the softest point, as well as what the spread in between will be. At what point will the music accelerate, at what point do you pull it back? What style of music do you want to use? What mood do you want to convey? You can almost graphically draw out a kind of gestalt if you like, or a template of the way the music will ebb and flow and work throughout the scene.

“All that is a given and is predetermined by the piece of film that you’re working with. You also keep an eye — and an ear, if you will — on the over-all effect of the music in that seven-minute scene with the rest of the music that you have done — or expect to do — within that particular film. There may be several ways of coming at all of this, but these are the parameters that are in place for that specific scene and for that specific movie, and they’re strong ones.”

Award-winning veteran journalist, critic, author, broadcaster and educator Dennis Polkow describes himself as being “a Monster Kid” for more than half a century.