The Chicago Symphony Orchestra’s Beyond the Score has covered some far-flung terrain since its first program 10 years ago. Using video projections, a narrated script and the occasional actor along with the orchestra, it has taken audiences to the hut in the Austrian countryside where Mahler completed his Symphony No. 4 and to England in a program titled “Mr. Haydn Goes to London.”

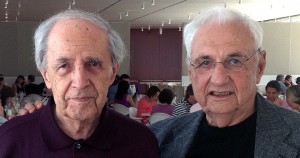

To open Beyond the Score’s 2014/15 season, Gerard McBurney, the CSO’s artistic programming adviser and creative force of BTS, has come up with something even more imaginative. Pierre Boulez, the eminent French composer and conductor who has been intimately involved with the CSO for more than 20 years, turns 90 in March. He will be the focus of a BTS program at 7:30 p.m. Nov. 14 and 3 p.m. Nov. 16 devised by McBurney with the eminent architect Frank Gehry and Mike Tutaj, an innovative Chicago projection and sound designer who has worked extensively with local theaters including Steppenwolf, Goodman, Chicago Shakespeare and TimeLine.

Typically, Beyond the Score programs sketch the story behind a single orchestral work, with the orchestra playing bits and pieces of the music as the story unfolds. After intermission, the orchestra plays the entire work — whether Bartok’s jagged, mysterious The Miraculous Mandarin or Vivaldi’s zesty The Four Seasons — straight through without interruption.

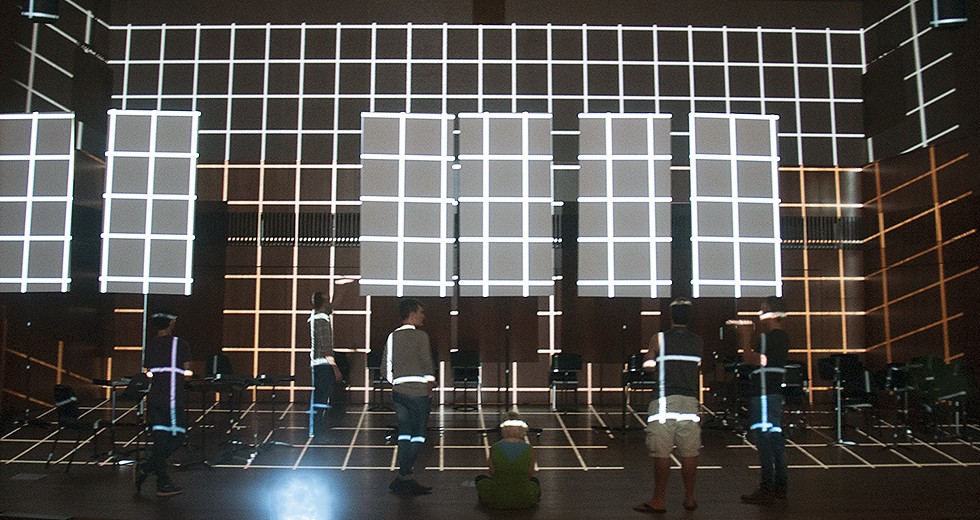

The Boulez program, 75 minutes long and aptly titled “A Pierre Dream,” has no intermission. Excerpts from Boulez’s atmospheric, translucent scores that span the full arc of his long career will be interspersed with video snippets and sound bites. Those range from Boulez as a ground-breaking composer and conductor in the 1950s to excerpts from interviews conducted last year at his home in Baden-Baden, Germany. The images will be projected onto a dozen video banners, 4 feet wide, standing 14 feet tall and mounted on poles, across the Orchestra Hall stage. Six of the screens will twist and turn, their poles manipulated by actors McBurney and his colleagues have taken to calling “puppeteers.”

“We’re coming up on 10 years that we’ve been making versions of [Beyond the Score], and I’ve always said I never wanted to repeat the same idea,” McBurney said. “It became clear early on that the elements in the shows that provoked the strongest reaction from the audience and musicians were where I distilled elements of theater and visual poetry and verbal poetry and made them, as far as I could, seamless with the music. I was making it less and less a lecture and didactic, and much more — to use a trendy, modern word — immersive. The experience leaves the audience, and indeed the musicians, free to interpret it how they want. The last thing I want is for somebody like me to tell another human being what to think about a piece of music.”

Fitting Boulez into the usual Beyond the Score format — story-telling before intermission and a full performance afterward — was challenging.

“Pierre never wrote a second-half orchestral piece,” McBurney said. “His full orchestral pieces are either short and scored for absolutely gargantuan orchestras, like Notations, which essentially makes them economically unviable. Or, if they’re scored for smaller orchestra, they’re scored in such a complicated way that they’re very unlikely to be done.”

Other orchestras perform the CSO’s Beyond the Score programs. After its CSO premiere, “A Pierre Dream” will travel to California for performances at the Ojai Festival and the University of California-Berkeley campus. In the coming years, it will be presented at the Netherlands Festival and the New York Philharmonic.

“There is a practical side to me,” McBurney said. “These shows are going around the world; I want them to be things that people can do.”

During an early rehearsal of the Beyond the Score production of “A Pierre Dream,” technicians work with the banners and projected images.

Gehry and Boulez have been friends for decades, meeting when Boulez was music director of the New York Philharmonic from 1971 to 1977. Gehry isn’t interested in attending traditional orchestral concerts, according to McBurney. But he was fascinated by Boulez’s so-called rug concerts, in which seats on Philharmonic Hall’s main floor were removed, and the audience sat on rugs and cushions. Gehry sketched out a general design concept for “A Pierre Dream,” and Tutaj, who worked with McBurney on four earlier BTS programs, refined his ideas.

“What we do is a kind of theater show about him in which we traverse Pierre’s whole musical life,” McBurney said. “We explore them in a kind of landscape, like you go to a sculpture park. And we needn’t stay too long in any of the pieces, which for some listeners would be daunting. If you chop the music up, it’s like flipping through a picture book. One of Pierre’s favorite artists is Cezanne. You flip through a book of Cezanne pictures, and you begin to get the idea of how he worked.”

Tutaj in 2013 brought an evocative blend of sound and images to his first BTS program, titled “The Tristan Effect,” that explored the world of Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde. “Mike’s projections were amazing,” said McBurney. “They absolutely transformed the space.”

“I always like to have something more interesting than a regular screen,” Tutaj said. But he also makes sure that his image and sound designs don’t overpower the people onstage. “A Pierre Dream” will feature 18 musicians, one singer and seven actors.

“I want to make sure that the reason you’re not at home watching TV is because there are live human beings onstage creating something beautiful,” Tutaj said. “We want to make sure that they are highlighted.”

Though the show will include quick cuts from interviews and video footage of Boulez, don’t expect a chronological march through the decades.

“We’re trying to paint a picture of the man,” Tutaj said. “We are telling a story, but we’re also floating through time, through the decades. It’s more dream-like; we can leap from one idea to another in a kind of free association.”

“If I’ve learned one thing from Pierre, he was always invested in breaking down the walls and windows,” McBurney said. “This is not to say that the traditional way of doing things is bad. It’s simply that everything must change all the time. … The problem for every artist, and work of art, is how do you shake people, how to you change them, how do you make them look at the world in a different way?”

Wynne Delacoma, classical music critic for the Chicago Sun-Times from 1991 to 2006, is a Chicago-based writer and lecturer.

TOP: A grid-like backdrop forms part of the design of “A Pierre Dream.”