For more than two decades, violinist Hilary Hahn has been a major presence on the classical-music scene, and so it’s easy to forget that she is just 36 years old. As a child, she gained almost instant fame, presenting her first full recital in 1990 at age 10, and appearing a little more than a year later with the Baltimore Symphony. By 16, Hahn had made her first recording, and she has continued to soar since, seamlessly making the potentially troublesome transition from child prodigy to adult artist. “In classical music, because the career trajectory is so long, ‘young’ extends quite aways,” she said. “I think I stopped being called a prodigy when I was 29 or 30, and it’s nice now to just be myself and not have a particular category assigned to me.”

Chicago audiences will get their latest chance to hear Hahn, joined by pianist Robert Levin, when she appears Nov. 1 as part of the Symphony Center Presents Chamber Music Series. The concert is the last stop on a four-city American recital tour that began Oct. 26 at Disney Hall in Los Angeles.

Robert Levin | Photo: Clive Barda/ArenaPAL

In addition to dazzling technique, what thrust Hahn into the spotlight in the 1990s was her preternatural depth and maturity. What has kept her there is her musical intelligence, creative imagination, genuine love of music-making and unquenchable desire to connect with audiences. Throughout her career, she has always made a point whenever possible to meet with attendees after concerts.

“When I was kid, I used to go to concerts and go backstage and meet people,” said Hahn, a native of Lexington, Va. “I was fortunate that I knew several people who worked in the Baltimore Symphony, and they would always make sure that I got to go back and meet the guest artists and visiting conductors. As a young musician, it gave me a chance to ask people questions about things that I was trying to figure out. I remember asking, ‘What did you do for school when you were a teenager?’ Things I didn’t have answers for, whether they were musical or practical.”

One time, she waited to meet a soloist whom she pointedly did not name. After 30 to 40 minutes, he rushed out and said that he had time to sign only a few programs before he had to leave for a boxing match. ‚ÄúIt seemed so frustrating because we weren‚Äôt there to particularly take up his time,” she said. “We just wanted to express our appreciation. I remember telling myself: ‚ÄòIf I‚Äôm ever in that situation where I have a chance to meet people, I‚Äôm going to do it.‚Äô‚Äù

As her career has advanced, Hahn has been able to become more selective about her concert schedule. But she was always exacting as young artist as well and did not grab every opportunity. Conductor David Zinman, one of her mentors, urged her to finish her schooling, which she did, graduating from Philadelphia’s Curtis Institute of Music at age 19. “A lot of people advised me that things would still be there later,” she said. “So take the things you want to take, but don’t feel like you have to take all the opportunities right now because they’re never going to come back. I don’t know if that’s being selective or it’s just thinking long term. For a lot of the stuff that I do now, it’s also still thinking long term.”

If all goes as planned, her Nov. 1 recital will conclude with a piece from one of her biggest successes to date: “In 27 Pieces: the Hilary Hahn Encores.” Launched in 2011, this imaginative commissioning program has sought to revitalize and redefine the often-overlooked short form. For the project, Hahn invited 26 composers, including Mason Bates, Jennifer Higdon, Nico Muhly and Einojuhani Rautavaara, and chose the final participant via an online contest. After presenting these short works on tour, she recorded them with pianist Cory Smythe. That disc won a Grammy Award in 2015.

But the project is from over. Capitalizing on a recent surge in interest in LPs, Deutsche Grammophon plans to release a vinyl version of “In 27 Pieces” in December. ‚ÄúI‚Äôm all for that,‚Äù Hahn said. ‚ÄúI think it is a unique listening experience. I grew up very aware of vinyl as a major form of listening to music. It wasn‚Äôt just a trendy, retro thing. We had LPs in our house and a record player, so I have a sentimental attachment to that form, and I‚Äôm always happy when a record gets released on vinyl.‚Äù

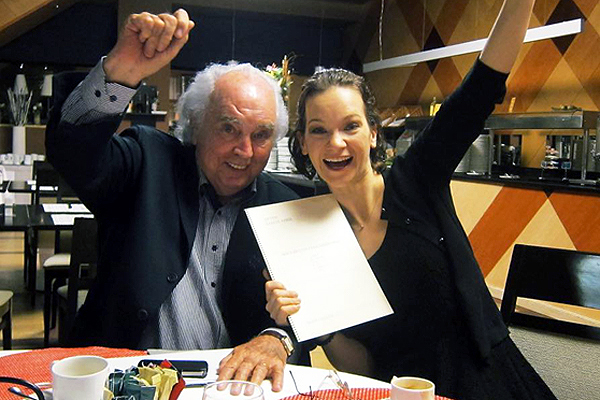

Hilary Hahn joins composer Ant√≥n Garc√≠a Abril, whom she commissioned to write a set of six solo partitas, in a bit of merriment.¬Ý

In addition, Hahn has been working toward the December release of digital and printed editions of the sheet music for the encores that will include fingerings, bowings and performance notes, along with insights she has gleaned from the composers. She hopes to provide a “quick point of entry” for anyone who wants to play the pieces.

And, of course, the project continues through the concert hall. Other violinists have added some of the encores to their repertoires, and she plans to play the works at her recitals for the foreseeable future. That means the likely chance of hearing at least one at Symphony Center. “Unless no one wants an encore,” she said. “If they stop applauding, we’re not going to force it on anyone. But if people want an encore, there will be something from the project. I don’t want to jinx it.”

Among other benefits, the encores exposed Hahn to a range of composers. She so was taken with the music of 83-year-old Spanish composer Ant√≥n¬ÝGarc√≠a Abril that she and the Washington (D.C.) Performing Arts commissioned him to write a set of six solo partitas in a polyphonic or multi-voice style inspired loosely by¬Ýthe works of Johann Sebastian Bach. In Chicago, she will perform Garc√≠a Abril’s Partita No. 4, which had its world premiere in Los Angeles.

Garc√≠a Abril’s six partitas belong to an unusual sub-genre of solo violin works that in addition to Bach‚Äôs famed six sonatas and partitas includes Heinrich Wilhelm Ernst‚Äôs Six Polyphonic Studies for Solo Violin and Eug√®ne Ysa√øe‚Äôs Six Sonatas for Solo Violin.¬ÝThese new one-movement partitas manage to be virtuosic and lyrical, Hahn said, and they are suffused with emotion. ‚ÄúSo when he writes polyphonically, he‚Äôs writing a complete story into his music,” she said. “The voices aren‚Äôt just counterpoint. It‚Äôs like a doing a one-woman show with multiple characters having conversations. It‚Äôs kind of a challenge but it‚Äôs also fantastic.‚Äù

Here’s what the violinist she had to say about rest of her program:

- J.S. Bach, Violin Sonata No. 6 in G Major, BWV 1019 — “Bach was so progressive. People don’t generally give him credit for being as progressive as he was. But he had such a sense of humor in his writing, and he did so many unexpected things, like just a turn of melody or a turn of harmony, and the individual moments are so surprising. As a performer, you’re always to bring this stuff out and tie it together. I’ve played so many of his works, but I have not done the duo sonatas, so I’m really excited to start that process with this one.”

- Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, Violin Sonata in E-flat Major, K. 481 — “Mozart sonatas are brilliant, and I think everyone already knows them pretty well. But they all have their own character, and Mozart is a challenge, because people might think of his music as polite, but you can’t really play it polite. Sometimes it’s hard to play something so it sounds joyous, and sometimes it’s hard to play something so it’s really touching. You can feel it inside, but conveying that with Mozart is a really interesting process, because he wrote so well for all these instruments; it’s such exposed music and it’s so clear where the music needs to go. It’s an interesting balance of being on your toes and being in the music. I love playing Mozart for that reason.”

- Hans Peter T√ºrk, Tr√§ume (Dreams) for Solo Piano ‚Äî ‚ÄúThis is a solo piece that Robert is playing. Since I‚Äôm playing a solo piece that is written for me, I asked him to play a solo piece written for him.‚Äù Levin met the composer¬ÝHans Peter T√ºrk¬Ýat an improvisation class in Cluj, Romania. Taken with the theme that T√ºrk offered him, Levin asked him to write a work for solo piano. The composer demurred, saying that any such work would have to be for his wife, a pianist. After the composer‚Äôs wife died, he agreed to write a piece for Levin, with the title taken from his wife‚Äôs notebooks in which she tried to record her dreams.

- Franz Schubert, Rondo in in B Minor, D. 895 ‚Äî ‚ÄúThe Schubert Rondo is a spectacular piece. Rondo is a deceptive title, because it makes it sound like a little polite romp through the park, and it really is not at all. It starts with this sort of declaration of drama, and it‚Äôs not at all what you expect out of a rondo. Then goes into a barn-burner ending, and somewhere along the way, it goes through all these different expressive features. As a performer, it‚Äôs a bit challenging, because you want to keep thinking of it as one type of piece or another, but it‚Äôs actually many different types of pieces in one.”