French music of the early 20th century, especially the music of Debussy and Ravel, sounds unlike anything that came before. You listen to a few measures of Debussy’s La Mer or Ravel’s Daphnis and Chloé, and you can’t possibly mistake it for the music of Strauss, Mahler, Puccini or any other composer of that time. The Impressionists (Ravel and Debussy) speak to us through a unique musical language. For them, the orchestra was a kaleidoscope of exotic sounds, with their creations full of evocative rhythms and stunning combinations of orchestral timbres. Thanks to the Impressionists, French musical culture was able to make the leap from 19th-century Romanticism to the radically new musical landscape of the 20th century.

Ravel, who lived from 1875 to 1937, wrote no symphonies, and yet he is one of orchestral music’s most frequently performed composers. Musical architecture did not interest him as much as the exploration of color and texture. To borrow a term from the Twitter generation, Ravel is trending — and has been for the past century. Almost everything he penned was successful. His Boléro, Daphnis and Chloé suites, La Valse and Rapsodie espagnole are regularly programmed by the world’s great orchestras.

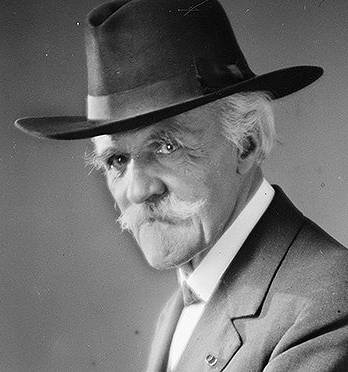

Sounding completely unlike Ravel, and yet a major influence on the generation of French musicians who preceded Impressionism, was composer-pedagogue Vincent d’Indy. Born in Paris into a family of Catholic aristocrats, d’Indy could trace his ancestry back to Henri IV. Over his long life, he produced 105 scores. These days most are rarely heard in performance. His Symphony on a French Mountain Air, which the CSO, under Charles Dutoit, will perform March 12, 14 and 17, is the exception.

D’Indy was one of those 19th-century characters who seemed to be everywhere. In 1873, he traveled to Germany and met both Liszt and Brahms. In 1875, he was the prompter for the premiere of Bizet’s Carmen. In 1884, he was the choirmaster for a production of Wagner’s Lohengrin, and he attended and was greatly influenced by the first production of Wagner’s Ring cycle at Bayreuth in 1876. He, along with organist Alexander Guilmant and conductor Charles Bordes, founded the Schola Cantorum in 1894. While music was racing toward 20th-century modernism, d’Indy through his Schola Cantorum cast a backward glance, emphasizing the study of Gregorian chant, Renaissance polyphony and works of the late Baroque and early Classical periods.

D’Indy had come from wealth. His upbringing was supervised by a tyrannical and rigid grandmother who would make him stand in front of an open window during thunderstorms. (This exercise was supposed to conquer his fear of lightning.) Early on he started piano lessons, and at 14, began the serious study of harmony. As a child, he loved playing with toy soldiers and was passionate about all things military. So much so that in 1870, he enlisted in the National Guard at age 19 when the Franco-Prussian War broke out. His grandmother was delighted with her grandson’s development.

After the war, he went back to his musical studies. He entered the Paris Conservatory in 1872 and became a student of composer-organist César Franck (1822-1890). Germanic in his musical outlook, an admirer of Wagner and an ardent worshiper of Beethoven, Franck inspired plenty of French musicians, especially d’Indy.

Franck came from Liège in what is now Belgium. His father wanted him to be a piano virtuoso and bullied the young Franck into accepting performance dates. The reviews were never glowing, and the young Franck retreated to the organ loft and conservatory to become a composer-organist and eventually a pedagogue. Like D’Indy, he influenced and inspired generations of French musicians. Two of his most famous orchestral works are his Symphony in D Minor, and his Symphonic Variations for Piano and Orchestra, which premiered in 1885, a single year before d’Indy’s three-movement Symphony on a French Mountain Air.

D’Indy had a long career, teaching at the Schola Cantorum until his death in 1931. Among his many students were Isaac Albéniz, Arthur Honegger, Darius Milhaud and for a few months in 1920, Cole (“Anything Goes”) Porter.

Chicago-based writer Jack Zimmerman has authored a couple of novels, countless newspaper columns and was the 2012 recipient of the Helen Coburn Meier and Tim Meier Arts Achievement Award.

TOP: An etching of Vincent d’Indy on the podium.