Violinists and critics sometimes speak of the “Big Five” violin concertos, a list that typically includes the celebrated works in the form by Beethoven, Brahms, Bruch, Mendelssohn and Tchaikovsky. According to research by the League of American Orchestras, two of these works rank among the 25 most performed works by league members. It just so happens that both will be featured on Chicago Symphony Orchestra’s 2017-18 season: Tchaikovsky on Sept. 23 and 26 with soloist Anne-Sophie Mutter and Mendelssohn on Nov. 30 and Dec. 1-3 with soloist Gil Shaham.

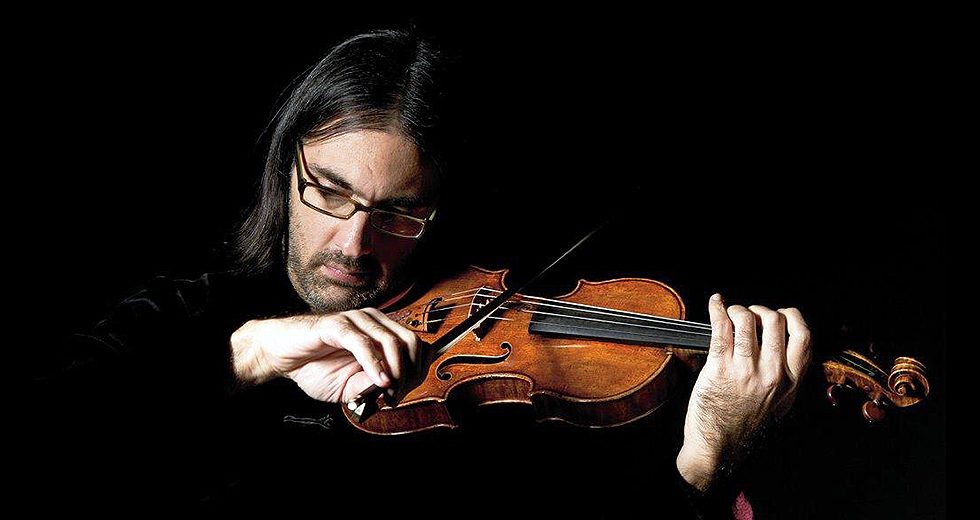

Gil Shaham

But this list of top concertos is not hard and fast. Some versions, for example, substitute Jean Sibelius’ Violin Concerto for Beethoven’s. But inexact or not, the “Big Five” is nonetheless a starting point in establishing the foundational concertos for the instrument, ones that virtually all major mainstream violinists perform regularly. There are, of course, many others that are frequently performed and admired. In March, for example, Gramophone magazine offered its picks for the 10 greatest violin concertos, which in addition to the traditional Big Five included the one by Sibelius as well as Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart’s Violin Concerto No. 3, Alban Berg’s Violin Concerto, Béla Bartók’s Violin Concerto No. 2 and Dmitri Shostakovich’s Violin Concerto No. 1.

Shaham recalls attending an art-history seminar about Madonna and child paintings in which it was made evident how artists like Botticelli and Titian looked back at the works of past masters. “So you have these centuries of what we now call classic Madonna and child paintings,” Shaham said. “That is a little bit what happens in our musical world with the violin-concerto form.” He pointed to the similarities between the Mendelssohn and Sibelius concertos, noting that Sibelius was a violinist and had played and studied the earlier work before completing his take on the form in 1904-05. “If you overlay them,” Shaham said, “it’s very clear that without the Mendelssohn Concerto, the Sibelius wouldn’t have sounded the way it does.”

Among the works for the combination that become the most popular in recent decades, at least in the United States, is Samuel Barber’s Violin Concerto, Op. 14, which the CSO will perform Oct. 26-27 with guest conductor James Gaffigan and soloist James Ehnes. The American composer completed the work in 1940 and revised it eight years later, with the definitive version receiving is premiere in 1949 with violinist Ruth Posselt and the Boston Symphony.

Despite its initial success, the concerto fell into virtual obscurity. Its comeback got an important boost in 1994 with Shaham’s fine recording with conductor André Previn and the London Symphony Orchestra. “I love that piece,” Shaham said. “It’s one of the great masterpieces. People have called it the great American violin concerto.”

VIOLIN CONCERTOS programmed for the 2017-18 CSO SEASON

Sept. 22: Mozart Violin Concerto No. 5 (Turkish), with Anne-Sophie Mutter.

Sept. 23, 26: Tchaikovsky Violin Concerto, with Mutter.

Oct. 26-27: Barber Violin Concerto, with James Ehnes.

Nov. 9-11: Berg Violin Concerto, with Arabella Steinbacher.

Nov. 30, Dec. 1-3: Mendelssohn Violin Concerto, with Gil Shaham.

Dec. 21-23: Beethoven Violin Concerto, with Nikolaj Znaider.

March 8-11: Shostakovich Violin Concerto No. 1, with Leonidas Kavakos.

May 11-12 and 15: Schumann Violin Concerto, with Isabelle Faust.

As some concertos gain in recognition, others fall out of favor. Shaham noted that Édouard Lalo’s Symphonie espagnole in D Minor, Op. 21 (1875), which despite its title is essentially a violin concerto, is played considerably less today than it once was. Much the same is true for Henryk Wieniawski’s now little-known Violin Concerto No. 2 in D Minor (1862). The violinist is not sure what the reasons are for such rises and falls. “I always wonder,” Shaham said. “Sometimes, it is very practical things like what fits for orchestras and conductors. Maybe there is this kind of cycle of fashion, that things ebb and flow and become more or less popular.”

Certainly, personal experience and preferences figure into the mix. Shaham recalls that celebrated violinist Yehudi Menuhin was not a fan of the Sibelius Violin Concerto and thus never performed it. Shaham himself has never played Robert Schumann’s Violin Concerto in D Minor (1853), which the Chicago Symphony will present May 11-12 and 15 with soloist Isabelle Faust. Although famed violinist Joseph Joachim played the work privately at the time of its completion, it did not receive its formal premiere until 1937, when Georg Kulenkampff unveiled it with the Berlin Philharmonic. “I don’t have any experience with it,” Shaham said. “Just for me, I wonder if I’d be able to pull off the last movement.” The final section is a polonaise, with a “lively, but not fast” tempo that some performers have found tricky.

Geographical differences also factor in. Shaham noted that in Great Britain and some of the countries of the British Commonwealth like Australia, the violin concertos of British composers Edward Elgar and William Walton are commonly performed. In China, Taiwan and Singapore, the best-known violin concerto is arguably The Butterfly Lovers’ Violin Concerto, written in 1959 by He Zhanhao and Chen Gang when they were students at the Shanghai Conservatory of Music. (The Civic Orchestra performed it as part of a Chinese New Year concert last season.) Composed for a Western-style orchestra, it incorporates many Chinese melodies and harmonies. Shaham released a recording of it with the Singapore Symphony Orchestra in 2007. “If you go to Singapore, China or Taiwan,” he said, “and you go for a morning stroll in the park, you will hear somebody doing tai chi to The Butterfly Lovers’ Violin Concerto.’”

But as noted, when Shaham returns to the CSO later this year, there will nothing so exotic on tap. He will perform one of the Big Five violin concertos: Mendelssohn’s Violin Concerto in E Minor, Op. 64, which was premiered in 1845. He noted several unconventional aspects of the work, including a technique that he called “richochet bowing,” a cadenza placed in the middle of the first movement instead of the end, as is customary, and a conclusion to that same section that consists of a solo sustained B on the bassoon that serves as a bridge to the second movement.

“When I think about the Mendelssohn, it’s always amazing how fresh and revolutionary the writing is,” he said. “I think people don’t necessarily think of Mendelssohn that way, but here is a composer who was so fluent with his craft that he was really able to take risks and innovate. That may be part of that piece’s success — it still sounds modern.”

TOP: Leonidas Kavakos will join the CSO in Shostakovich’s Violin Concerto No. 1. on March 8-11. | Photo: ©Marco Borggreve