Though their names might have been forgotten in the march of time, composers Florence Price and Margaret Bonds share historic ties to Chicago and the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. Even more significant, both achieved milestones in a field dominated, as one critic recently put it, by “the white, male and dead.”

To be a female composer in the classical music world of the mid-20th century was unusual. Even more unusual, Price and Bonds, both residents of Chicago, were women of color. Despite what many viewed as obstacles, they forged ahead and made history. At a Chicago Symphony concert on June, 15, 1933, conducted by then music director Frederick Stock, Price became the first black woman to have her work performed by a major orchestra, while Bonds was the first African American to perform as a soloist alongside the CSO.

Pianist and scholar Samantha Ege will join the CSO’s African American Network for a recital and lecture April 12 at Club 8.

Their legacy will be the focus of a recital and lecture titled “A Celebration of Women in Music — Composing the Black Chicago Renaissance,” presented by the CSO’s African American Network at 5:30 p.m. April 12 at Symphony Center’s Club 8 and featuring music scholar and pianist Samantha Ege. On the program will be Price’s Sonata in E Minor and Bonds’ Troubled Water.

Price’s and Bonds’ achievements came as a result of the 1932 Rodman Wanamaker Foundation Awards. Price won first prize for her Symphony in E Minor, while Bonds took first place in the song category. Stock arranged to have Price’s symphony performed at the 1933 concert and invited Bonds, a piano virtuoso, to perform John Alden Carpenter’s Concertino for Piano and Orchestra on the program. Winning the Wanamaker honor “was a significant accomplishment in itself,” said Ege, a doctoral candidate whose research centers on Price. “However, the premiere of Price’s Symphony in E Minor catapulted Price to a level of recognition that was unprecedented.”

That level of recognition was not to last. After the CSO breakthrough, Price found few ensembles willing to program her compositions. In 1943, she sent a blunt letter to Serge Koussevitzky, then music director of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, asking him to consider her works: “To begin with I have two handicaps — those of sex and race. I am a woman, and I have some Negro blood in my veins. Knowing the worst, then, would you be good enough to hold in check the possible inclination to regard a woman’s composition as long on emotionalism but short on virility and thought content, until you shall have examined some of my work?” Koussevitzky reportedly carried on a correspondence but never publicly took up Price’s cause.

In an email interview, Ege shared more observations on the remarkable sagas of Florence Price and Margaret Bonds:

How influential was Frederick Stock in Price’s and Bonds’ careers?

There is an anecdote in Price’s diary that gives us insight into how Stock regarded both her and Bonds. Price runs into Stock on Michigan Avenue. They greet each other warmly, and he asks her what she is working on. She tells him about her piano concerto, and he is very pleased. He suggests Bonds, who he recalls played Carpenter’s concerto so well, should learn Price’s concerto so it can be performed. He clearly recognized just how masterful they were in their craft. His progressive programming gave Price and Bonds a platform that brought them to mainstream attention.

In a recent paper, you raise these questions: “How did Price negotiate the obstacles of gender and race? How did she cultivate an aesthetic that is distinctly and intrinsically American? The answers … are entangled with the politics of her existence.” You’ve written at length on these topics, but could you offer a quick summary in response?

Price recognized African-American folk music as an integral part of the American musical fabric. By choosing to embrace and uplift musical traditions that are so embroiled in the history of slavery, she found a way to reconcile past and present. Price was very aware of the obstacles of being a black American woman, especially one composing in a classical sphere. However, this awareness connected her to a network of practitioners with similar heritage, and the communities that she became a part of were crucial in her navigating the obstacles ahead.

Bonds was Price’s student for a time, and they were also friends. How did this friendship impact their careers?

Again, the word community comes to mind. Though we often speak of Price as the first African-American woman to achieve national and international success, we cannot isolate her achievements from the network who supported her. When Price faced financial straits, Bonds’ mother, Estella, welcomed her into their home. When Price had deadlines to meet for music contests, the Bonds were there, helping her to meet those deadlines. And with Margaret Bonds being a chief interpreter of Price’s piano works, these works became a vehicle for Bonds’ talent. Their friendship was truly about uplifting one another.

Again, the word community comes to mind. Though we often speak of Price as the first African-American woman to achieve national and international success, we cannot isolate her achievements from the network who supported her. When Price faced financial straits, Bonds’ mother, Estella, welcomed her into their home. When Price had deadlines to meet for music contests, the Bonds were there, helping her to meet those deadlines. And with Margaret Bonds being a chief interpreter of Price’s piano works, these works became a vehicle for Bonds’ talent. Their friendship was truly about uplifting one another.

Nadia Boulanger, widely regarded as the most influential music instructor of the 20th century, once told Bonds she had nothing to learn from her?

When I learned about Bonds’ desire to study with Nadia Boulanger at the American Conservatory at Fontainebleau and the exchange that transpired, I was quite surprised that a teacher, particularly one held in such high regard, would turn a prospective student away on the grounds that there was nothing they could learn from them. What is beginning to emerge, particularly through the work of Kendra Preston Leonard, is that Nadia Boulanger was, indeed, a very complex woman who did not operate outside the realm of prejudice and discrimination. Quoting from Leonard’s recently published article “Mademoiselle Myths”: “Boulanger and the Conservatoire administrators in New York worked to keep the number of minority students, including blacks and Jews, low.” This certainly gives Boulanger’s response to Bonds a new context. In any case, Bonds clearly was not discouraged.

Did actually Price pretend to be Mexican to avoid the prejudice displayed toward black Americans?

I think this is quite possible. The New England Conservatory of Music did actually accept African-American students, but it could not be guaranteed that this progressiveness would extend to the mentalities of the people within this institution. Price’s mother had the foresight to list her daughter’s nationality as Mexican as a means of survival more than anything else.

The famous letter that Price wrote in 1943 to Serge Koussevitzky, asking him to consider programming her music, is heartbreaking. And yet 75 years later, have things changed that much?

There have been many exciting recordings and performances happening around Price’s music, from Er-Gene Kahng’s recent recordings of the violin concertos to Chineke! Orchestra — Europe’s first professional majority black and minority ethnic orchestra — performing her Symphony in E Minor. So have things changed that much? Yes. But to certain extent, also no.

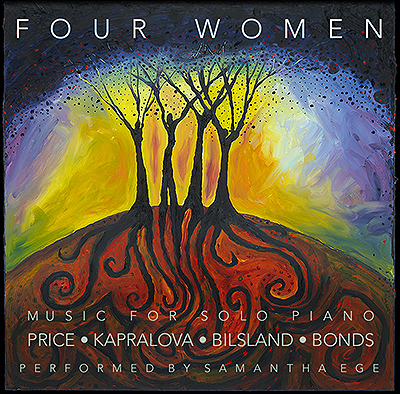

In May, Wave Theory Records will release your album “Four Women,” which spotlights the piano music of Florence Price, Ethel Bilsland, Vítězslava Kaprálová and Margaret Bonds. Tell us more about this project.

The title comes from Nina Simone’s song of the same name written in 1966. Each verse tells the story of an African-American woman who is trapped in her stereotype, despite seeking her own self-definition. To a certain extent, Simone was trapped in a similar way. She aspired to be a classical pianist, but was rejected from this path on the grounds of her race. Simone, as we know, pursued a highly successful career in jazz, but like the four women in her song, her path was affected by external prejudices. “Four Women: The Piano Music of Vítězslava Kaprálová, Ethel Bilsland, Florence Price & Margaret Bonds” continues the conversation. I tell the musical stories of another four women who were not immune to prejudice, but certainly carved an existence for themselves outside of social expectations. Perhaps there is controversy in my choice to not only tell the stories of black women, but I think the bigger controversy is that Simone — the classical pianist we will never know — had no choice. “Four Women” brings Simone’s theme of self-definition into the classical realm, and just like Simone’s “Four Women,” encourages us to look and listen beyond stereotypes.

Samantha Ege performs works by Price and Bonds on her upcoming disc “Four Women.”

How did you settle on these four composers as your focus?

Price and Bonds were such a huge revelation to me, I previously had no idea that black women had lived as classical composers. Exploring their repertoire has been such an empowering process and that is one of the many things represented by their inclusion in this album. I first performed Price and Bonds at an event hosted by the British High Commissioner in Singapore. The invitation inspired my first women composer-centered program, and that program is what led to the amazing experience of recording for this album. Bilsland’s music represents the authentic connections we can make with others over music and a shared commitment to gender equality. Kaprálová has inspired me on such a personal level. She died at the age of 25, but what she achieved in her short life was monumental. Her music reminds me of what it means to find beauty when you pursue your truth and creativity. Wave Theory Records entrusted me wholeheartedly with the content, strongly believing that these women needed to be heard. Price, Bilsland, Kaprálová and Bonds play such an essential role in my story, but this album also gives me the opportunity to tell theirs.

If you could program a work by Price and Bonds for a concert, which works would you select?

I would choose Price’s Piano Concerto in One Movement; it’s a magnificent journey through all of Price’s musical and cultural inspirations. I would also propose an orchestral arrangement of Bonds’ Spiritual Suite, originally composed for solo piano. “Troubled Water” is the third movement in this suite, and it is a piece that you never forget. Hearing this movement in the context of the full suite really immerses you in the African-American folk sound world. But having all the shades and tones of this suite amplified by orchestral colors would be quite the experience.

Price and Bonds have significant legacies and yet both remain relatively unknown outside scholarly circles. In a recent New Yorker essay, critic Alex Ross offered a partial explanation: “We stick with the known in order to avoid the hard work of exploring the unknown.” Would you agree?

I would agree. There is a real danger in sticking to what we know. In doing so, we encourage society at large to perpetuate the same prejudices that Price and Bonds faced in their time. People may argue that it is not prejudice, it is that they simply prefer the more well-known composers — but does this argument really stand when we know that race and gender have created the most insurmountable barriers for some, and the greatest platforms for others? Exploring the unknown is also coupled with the hard work of examining our prejudices, but we become richer for doing so, as does our repertoire.