Roger Burney died aboard the French submarine Surcouf in 1942. David Gill was killed in action in the Mediterranean. Michael Halliday was declared missing in action in 1944. Piers Dunkerley was wounded and taken prisoner during the Normandy landings in 1944; he was released at the war’s end, returned to civilian life and planned to marry, but killed himself on June 7, 1959.

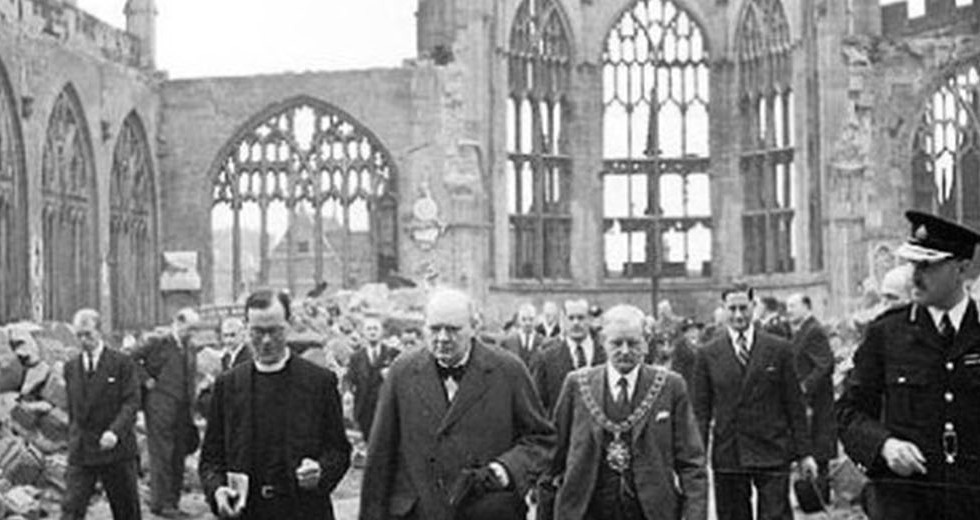

Photographs of these four men were found in an envelope among Benjamin Britten’s belongings after his death. They all knew the composer, none of them especially well, but to Britten, they were the faces of the dead — hauntingly familiar victims of war. As he sat down to write a requiem mass for the rebuilt cathedral in Coventry (the original church had been bombed to rubble during nightly air raids in November 1940), these four young men brought immediacy to the vast and unmanageable subject of war. As the War Requiem took shape, they personalized the tragedy of battle and helped him never to lose sight of individual private lives against the background of world history. It is these four names, unfamiliar to all but their family and friends, that Britten put on the dedication page of his War Requiem.

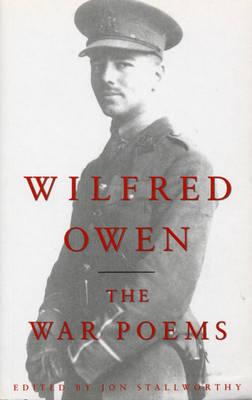

It was another dead soldier, the victim of an earlier world war, who gave voice to Britten’s lifelong pacifist views and provided much of the text for the Coventry requiem. Wilfred Owen died in action on Nov. 4, 1918, while leading his troops across the Sambre Canal in northeast France, exactly one week before the Armistice. (His parents didn’t receive the telegram of their son’s death until Nov. 11, the news bringing them face to face with grief while the rest of England cheered the end of World War I.) In later years, Owen slowly gained acclaim for the terse and moving verses he wrote in the trenches and on the battlefield. Britten knew him as the greatest of the First World War poets. He owned a volume of Owen’s work, and in 1958, when the BBC radio program “Personal Choice” asked him for his favorite poems, he included Owen’s “Strange Meeting,” the text he would ultimately use at the end of the War Requiem. That same year, Britten was approached by a member of the Coventry Cathedral Festival, which wanted to commission him to write a large work to consecrate the new cathedral nearing completion next to the ruins of the ancient building.

By the time Britten began to compose the score for Coventry in the summer of 1960, many deeply personal strands had come together: the loss of four friends, his interest in the war poetry of Wilfred Owen, his own staunch pacifist beliefs, the unshakable memory of visiting the concentration camp at Belsen with Yehudi Menuhin in 1945 before playing a recital for the victims’ families, his shock at the death of Gandhi in 1948, and a long-held desire to write a significant large-scale choral piece. Almost inevitably, this great public work also became one of his most private statements. Britten rarely referred to the requiem in his letters during the many months when he was hard at work on it, as if it were too personal to mention.

In his copy of Owen’s book, Britten marked nine poems he intended to set to music as part of the requiem. Almost from the start, Britten knew he wanted to weave Owen’s texts in with those from the mass for the dead — the juxtaposition of the ancient Latin service with these more recent reports from the battlefield underlining the confrontation of public and private, and of past with present, that gives the War Requiem its unsettling power. Before he sketched any of the music, Britten wrote out his libretto in an old school exercise book, with the mass text on the left page and the Owen poems facing on the right, arrows carefully showing just how they were to dovetail.

In his copy of Owen’s book, Britten marked nine poems he intended to set to music as part of the requiem. Almost from the start, Britten knew he wanted to weave Owen’s texts in with those from the mass for the dead — the juxtaposition of the ancient Latin service with these more recent reports from the battlefield underlining the confrontation of public and private, and of past with present, that gives the War Requiem its unsettling power. Before he sketched any of the music, Britten wrote out his libretto in an old school exercise book, with the mass text on the left page and the Owen poems facing on the right, arrows carefully showing just how they were to dovetail.

He set to work, declining three new commissions and postponing work on Curlew River so that he could concentrate on the Coventry mass. In the two decades since Britten’s “other” requiem, the purely instrumental Sinfonia da requiem, events had moved from bloody combat to the sobering reality of devastated cities, heartbroken families and mass graves. And 1961, the year Britten devoted to the War Requiem, was marred by the building of the Berlin Wall, an ominous escalation of U.S. action in Vietnam, and the incident of the Bay of Pigs. Owen’s poems, “full of the hate of destruction,” and Britten’s new score, with its call for peace, couldn’t have been more timely.

In February 1961, Britten wrote to Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, asking him to sing the baritone solos. Britten’s companion, Peter Pears, had already agreed to take the tenor part. Britten’s scheme was carefully drawn: these two soloists, accompanied by a chamber orchestra, would sing the Owen texts, as “a kind of commentary on the mass.” The Latin text itself would be given to full chorus and orchestra, along with a soprano solo and boys’ choir. It’s a blueprint shrewdly designed to point out the individual amidst the crowd, to acknowledge personal grief while preaching pacifism. That summer, when Rostropovich and his wife, Galina Vishnevskaya, came to the Aldeburgh Festival, Britten found his soprano. Vishnevskaya gave a recital in Aldeburgh, only days after Rostropovich played the premiere of the new cello sonata Britten had written for him. The night Vishnevskaya sang, Britten told her that he wanted to write the War Requiem soprano solo for her. She was the final link in his plan to bring together representatives of three nations devastated by the war: an English tenor, a German baritone and a Russian soprano (a symbolic casting that is replicated in this season’s Chicago Symphony performances).

During the summer, the playwright Christopher Isherwood sent Britten a book containing a photograph of Wilfred Owen. “I am delighted to have it,” Britten wrote. “I am so involved with him at the moment, and I wanted to see what he looked like: I might have guessed, it’s just what I expected, really.” That same summer, William Plomer, a friend of Britten, tracked down Owen’s brother Harold, but the composer decided not to visit him, no doubt fearing that it might somehow disturb the affinity he felt for the poetry itself. By August, Britten told his publisher, Boosey and Hawkes, that he had completed “the first large chunk” of the War Requiem (the title he had finally settled on), but two months later, he said, it “is always with me.” It was finished at last in January, while Britten and Pears were in Greece. “I was completely absorbed in this piece, as really never before,” he wrote to a friend.

In the spring, Britten heard from Rostropovich and Vishnevskaya, who had received the score and were both “mad” about the work. But a few weeks later, Britten lost his soprano: the Soviet authorities refused to allow Vishnevskaya to participate in the premiere; “the combination of ‘Cathedral’ and Reconciliation with W. Germany … was too much for them,” Britten said. “How can you, a Soviet woman,” the minister of culture asked Vishnevskaya, “stand next to a German and an Englishman and perform a political work?” British soprano Heather Harper stepped in, learning the role just 10 days before the performance.

Five days before the May 30 premiere, the critic William Mann wrote in The Times that the War Requiem was Britten’s masterpiece, a verdict that, though premature, proved accurate. The performance itself, despite the patchy rehearsals and the new cathedral’s “lunatic” acoustics, was stunning. Fischer-Dieskau was moved to tears. “The first performance created an atmosphere of such intensity,” he wrote in his autobiography, “that by the end, I was completely undone; I did not know where to hide my face. Dead friends and past suffering arose in my mind.” The newspapers printed a uniform chorus of praise. Stravinsky quipped that to criticize the work would be “as if one had failed to stand up for ‘God Save the Queen.’ ” Peter Shaffer, later the playwright of Amadeus, came closest to the mark when he wrote that the work was so profound and moving that it “makes criticism impertinent.”

During composition, Britten deviated very little from the scheme he had first written out in his exercise book: the six parts of the Latin text interwoven with nine poems by Owen — one in each part, except for the Dies irae, which includes four. The intent, as in the great Passions by Bach, is of text combined with commentary, although the effect — particularly in Britten’s assured mix of opera and oratorio — is closer to Verdi’s grand 19th-century requiem.

Britten divides his cast of characters into distinct groups: two soldiers, sung by the tenor and baritone soloists and accompanied by a chamber orchestra; the celebrants of the mass, which include the soprano soloist, a full chorus and orchestra, and from afar, a boys’ choir accompanied by organ. The scene shifts seamlessly from one group to another — cutting back and forth from the church to the battlefield. Only in the last pages of the final Libera me do all the performers come together.

Here, a funeral march introduces a large chorus of desolation and despair. The soprano enters, and the music builds to a chilling outcry. Slowly Britten clears the scene for the stark realism of Owen’s “Strange Meeting,” the poem he had long loved — a harrowing encounter between two enemy soldiers. With their last words, “Let us sleep now,” Britten weaves together all the performers in a slowly enveloping web of music. For a moment, he suggests a sense of universal understanding. But then the bells intone their anxious harmony, and the voices of the two soldiers can still be heard, before the chorus calls for peace. It’s a strangely uncertain ending, and we are reminded of the words by Owen that Britten chose not to set, but to place instead as an epigraph to his score:

My subject is War, and the pity of War.

The poetry is in the pity …

All a poet can do today is warn …

Phillip Huscher is the program annotator for the Chicago Symphony Orchestra.

PHOTO: Winston Churchill (center) visits the ruins of Coventry Cathedral. (Photo: British War Office)