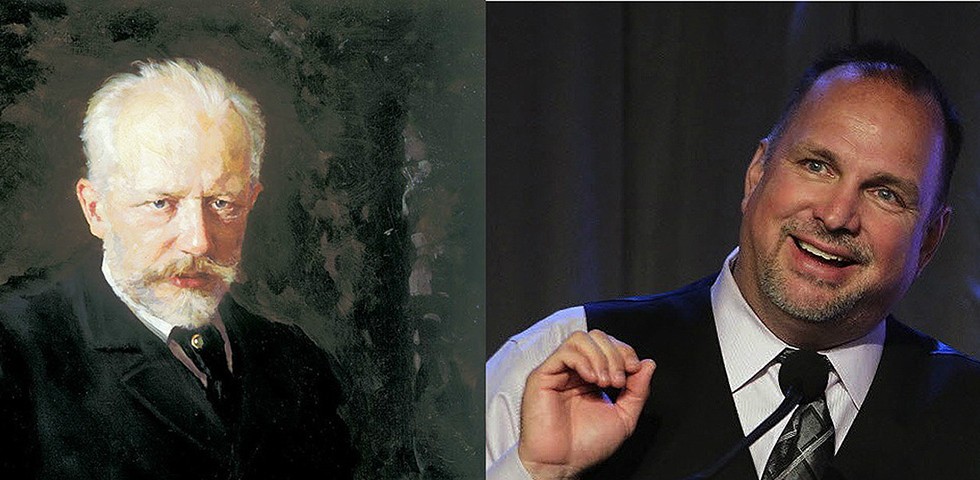

The big names in autumn concerts here are Piotr Tchaikovsky and Garth Brooks.

Over the next few weeks, Chicagoans will pack Orchestra Hall and Millennium Park for eight chances to hear the CSO in Tchaikovsky, America’s best-loved Russian melodist. Meanwhile, at the Allstate Arena, they’re jamming Rosemont lots and off-ramps for Brooks, the country-music megastar (who’s outsold Elvis Presley and Enrico Caruso — choose which suits you) making international headlines with his first tour in 15 years. Whether you favor lush violins or amped-up fiddles, Tchaikovsky and Brooks — the 19th and 21st century’s favorite musical populists — know just how to play a crowd.

Big in New York: Tchaikovsky headlined the 1891 opening of New York’s new Music Hall, renamed for tycoon Andrew Carnegie two seasons later. The composer conducted his own works and kept a notebook, Trip to America, in which he wondered, “What kind of hats do they wear?”

Brooks favors Stetsons. It’s been 17 summers since “Garthstock,” when 250,000 fans descended on Central Park for Manhattan’s most improbable hoedown. The CSO’s out to top that crowd when Music Director Riccardo Muti appears in the all-Tchaikovsky Concert for Chicago on Sept. 19.

Cannons clash and the thunder rolls: Boost the bass for “The Thunder Rolls” — Brooks chides a bad husband “headin’ back from somewhere that he never should have been” as ominous storm clouds rumble.

Tchaikovsky, similarly, chides Josephine’s old husband headin’ back from somewhere that he never should have been when Russian cannons pound Napoleon’s Grande Armée in the slam-bang finale of the 1812 Overture.

For God and country: The 1812 Overture — a curious Fourth of July concert staple — unleashes Tchaikovsky’s triumphant orchestra in Russia’s imperial anthem “God Save the Tsar!”: “Strong and majestic! Reign for glory! For our glory!”

Brooks shows his patriotic bona fides in “American Honky-Tonk Bar Association,” celebrating the homeland’s “hard-hat, gun-rack, achin’-back, over-taxed, flag-wavin’, fun-lovin’ crowd; their heart is in the music and they love to play it loud!”

Kentucky fiddlers and Texas ivory ticklers: Brooks has a violin champ in bandmate Jimmy Mattingly, the Kentucky fiddler whom the Oklahoma crooner counts on for down-home melodies like “Callin’ Baton Rouge.”

Tchaikovsky’s folk-inspired piano interludes remain the province of Van Cliburn, the late, lanky Texan who amazed Moscow at the 1958 International Tchaikovsky Competition but performed the composer’s Piano Concerto No. 1 with the CSO just once, at Ravinia in 1971.

Secret third verses and movements: Nothing brings down a Brooks house like his hit “Friends in Low Places,” when he implores the faithful to sing a supposedly “secret” third verse with Nashville’s most innocuous off-color reference, which they apparently learn from a vertical YouTube video.

Likewise, Tchaikovsky sketched a secret third movement for his unfinished Piano Concerto No. 3 — just the first movement was published, posthumously. Here’s another vertical YouTube video with pupil Sergei Taneyev’s speculation on how Tchaikovsky’s secret finale might have sounded.

If Brooks named Tchaikovsky’s masterworks: Symphony No. 1 (Winter Daydreams), which Muti and the CSO will revisit in January — “Why Don’t these Dreams Ever Come True?” Romeo and Juliet — “Papa Loved Mama.” The opera Queen of Spades — “Two of a Kind, Workin’ on a Full House.”

Georgia on their minds: Once Brooks’ first marriage ended in divorce, he got smitten with Monticello, Georgia, songstress Trisha Yearwood (“She’s in Love With the Boy”). Now married nearly a decade, country’s power couple is touring together, Rosemont shows included.

Tchaikovsky’s troubled marriage to music student Antonina Milyukova — they shared a home less than three months — gave him frequent reason to visit brother Modest in Tbilisi, Georgia, where the composer spent five summers.

Once quiet, now proud: Tchaikovsky’s silent preference for male company, which destroyed his nascent marriage, caused him deep personal torment in a Russia unaccepting of alternative lifestyles; this strong sense of melancholy punctuates his late symphonies.

Stateside and a century later, Brooks’ inclusive ballad “We Shall Be Free” (“We shall be free when we’re free to love anyone we choose/When this world’s big enough for all different views”) is a favorite of LGBT country fans.

Party over, Pete — party on, Garth: Worn out by rigors of recording and touring, a 38-year-old Brooks surprised Nashville by announcing his retirement in 2000. In 1893, the 53-year-old Tchaikovsky, worn out by bad tap water, surprised St. Petersburg by conducting his new Symphony No. 6 (Pathétique) and dying of cholera nine nights later.

Fourteen years down the road, Brooks is in Rosemont kicking off his comeback, and 121 winters later, Maestro Muti will probably stick to San Pellegrino for the CSO’s performances in February and March of Tchaikovsky’s last masterpiece.

Andrew Huckman is a Chicago-based writer and lawyer.