Stewart Copeland knows epic. After all, he was the co-founder and drummer of one of the rock world’s biggest bands, the Police. After the group broke up in the mid-1980s, he went on to write scores for Hollywood blockbusters such as “Wall Street” (1987), and then he tackled the most epic of all arts, opera.

But nothing prepared him for the power of witnessing — and participating in — the world premiere of “Ben-Hur: A Tale of Christ” earlier this year at the Virginia Arts Festival, in Norfolk, Va. Copeland had written a new score for the 1925 silent film, based on the best-selling 1880 novel, which depicts a life-altering encounter between a prince turned slave and the prophet known as Jesus of Nazareth, set against pirate-led battles at sea and death-defying chariot races in ancient arenas. Along with composing the score, Copeland had spent over five years clearing the rights to use the movie, curating a new digital version of the silent epic and getting the mammoth enterprise off the ground.

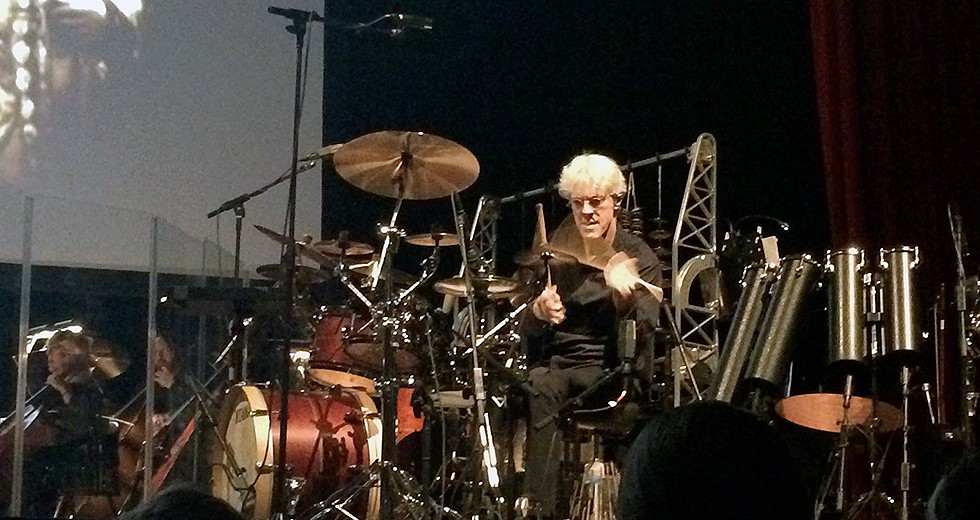

So when the curtain rose in April, as he and a full orchestra prepared to perform his score as the movie flashed overhead, he thought he knew what to anticipate. “I expected the chariot race to rock. I expected the pirates to be amazing. But what I didn’t expect was this really powerful and emotionally uplifting spiritual message,” recalled Copeland during a promotional stop here last week, ahead of the SCP Special Concert on Oct. 14 featuring “Ben-Hur: A Tale of the Christ,” performed by the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Richard Kaufman and with Copeland on drums and percussion. “I had forgotten the power of that movie. The night of the world premiere, it all came together, all of our efforts and all of my practicing. But I don’t think anyone noticed any of that.”

Even Copeland’s most devoted fans were mesmerized by the movie — not the object of their usual affection. “I have a claque, a crazy group of followers who get what I do and who follow me around from concert to concert,” he said. “At the world premiere, I looked out and saw that even those familiar faces, they were blown away by the movie, not me. Afterward they were saying, ‘I can’t believe I forgot to watch Stewart during the performance.’ ”

“Ben-Hur” has been casting a spell for decades. The most expensive film of the silent era, with a budget of $4 million (about $55 million in 2014), it was filmed over two years on two continents, with primitive Technicolor employed for special scenes. The lavish production almost crippled the nascent studio MGM, which inherited the project when Goldwyn Pictures, Metro Pictures and Mayer Productions merged in 1924. The film’s epic scale required several directors (with Fred Niblo gaining the sole credit), more than 60 assistant directors and the proverbial cast of thousands, with silent icons Francis X. Bushman (Messala), May McAvoy (Esther) and the Mexican-born Ramon Novarro, Hollywood’s first Latino star, in the title role.

After a successful re-release in 1931, the silent “Ben-Hur” remained largely forgotten, especially the phenomenal popularity of the 1959 Oscar-winning remake, directed by William Wyler (an assistant on the 1925 version) and starring Charlton Heston, Stephen Boyd and Jack Hawkins. Though the 1959 version won the laurels, many film buffs regard the silent take as the better of the two. “The spectacular silent epic is only about as half as long as the elephantine 1959 William Wyler remake, yet is at least twice as entertaining,” wrote a TV Guide critic. ” … ‘Ben-Hur’ may be a hokey religious pageant of sin and salvation, but as an example of the kind of ornate and profligate spectacle that just couldn’t be made anymore, it’s a lot of fun.”

That ornate and profligate spectacle is what attracted Copeland to this project, which began about five years ago as a live-action arena event, with actors re-creating the film’s battles and chariot races. The show’s producers hired him to write and perform a new score. “But then the market crashed, the money evaporated,” Copeland said. “Yet we had all these forces lined up on the starting line, so to speak, and no one wanted to pull the plug.”

Especially not Copeland. “I had drunk the Kool-Aid by then,” he said, laughing. “I really believed in the project.” So then his manager suggested the idea of editing the movie for a live orchestra-screening experience. That required going back to original celluloid reels, which since the ’60s had been locked up in the vaults of Warner Bros. (WB had gained control over the MGM library), and cutting the film down to a more manageable running time of 90 minutes. A technology buff, Copeland did the curating himself. “So we dug up the old print, and I telecined [made an edited digital copy] it.”

Though Copeland had scored dozens of movies, beginning with Francis Ford Coppola’s “Rumble Fish” in 1983, he had never before tackled a silent film.”I had worked with Coppola and [Oliver] Stone [on “Wall Street”], and that was like a boot camp of how to make music do a specific thing, to hit a specific emotional note,” he said. “So when I got to this project, all that technique came in handy.”

Still, some might question the wisdom of a rock drummer taking on such a task. Copeland understands the skepticism, but adds, “It’s not rocket science. The art part I learned by telling the story as a professional composer working with editors. I don’t know to shoot a movie but I know how to cut a movie because I’ve been with directors in post[-production], trying to cure scenes, find out what the purpose is,” he said. “So I learned how to tell a story with editing. That’s how I learned the art side. the mechanical side of it, I’m just an app freak.”

Best of all, he said, “I got to be the boss. I’m guilty of occasionally calling it my movie because there’s no one else around. As a film composer, I had directors beating me up all the time. That’s my job and I’m very glad of it because that’s where I learned my chops.”

But he remains humbled by the artistry of director Niblo and his creative team. “The filmmakers of that period didn’t have the tools that we have now, so they had to make up for that with other creative solutions,” he said. “Silent films might seem hokey to modern audiences, but when you look closely, you see how much thought went into every frame. ‘Ben-Hur’ is truly a work of art.”

In Chicago, Copeland will be joined again by conductor Richard Kaufman, who suggested bringing “Ben-Hur” to Symphony Center for the project’s second engagement (since then, it has been booked for runs in Berlin and Paris). At Norfolk, Copeland and the orchestra were amplified but they will go acoustic here. “It’s going to be tough,” he said, laughing. “But it’s good for me.”

Copeland doubts that he’ll ever score another silent film; his main interest now is composing operas (his fourth effort, The Tell-Tale Heart, received its U.S. premiere last year at Long Beach Opera, the sister company of Chicago Opera Theater). But he has been enlightened by the “Ben-Hur” experience. “I’m an aetheist, a Los Angeles libertine, but I was really moved this movie, and I became a better person, briefly,” he said, laughing again. “But I really do feel that I learned something spiritually from this movie. When I see the Jesus scenes, I get why Bach wrote such great music, inspired by religion. You know, it’s the same as romance takes you to a place that makes the music flow. I’m very proud of the music that I wrote. It’s the power of the knowledge that the Jesus character affects so much of our history. This is not just Pinocchio. To see these sentiments portrayed on the screen with such feeling is very moving.”

More from Stewart Copeland: An interview in the Sun-Times, segments on WGN Radio, WGN-Channel 9, WTTW-Channel 11 and a post on Classicalite.