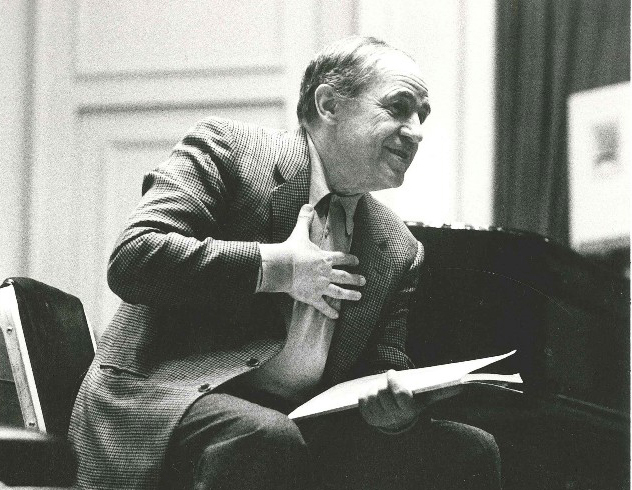

For many years, as part of his winter residency with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, composer and educator Pierre Boulez, who also was CSO principal guest conductor, gave a lecture at the Art Institute of Chicago. Dec. 4, 1994, he discussed the idea of the score as a subject of interpretation and questioned how effective a performer can really be. A portion of that lecture has been adapted and reprinted here.

Every year, I pick a subject that is very important to me and share my thoughts with you, and the topic I have chosen for today is “Score: Imagination and Reality.” That is a problem I am confronted with every day of my life, either as a composer or as a performer, and I know both sides, I think, quite well.

There are generally two approaches for composers and performers — the first is that everything is within the notes and, of course, the opposite is that everything is behind or beyond the notes.

The first approach considers the score as an object with precise date — pitches, rhythm, dynamics, tempos — all kinds of precise indication — supposedly precise indications. We will see later that they are not that precise. To do justice to the music, the composer and performer have to respect this data — to be faithful to the letter and the spirit will come by itself.

Some composers, such as Stravinsky and Ravel, have been very critical about the so-called freedom of the performer. But with an objective approach to the score, the individual is a transmitter — you reproduce almost mechanically what you see and nothing more. And I did not use the word “mechanically” for nothing. There was a time when Stravinsky was angry with performers; he tried to get rid of them and wrote a ragtime piece for mechanical piano. He also began a version of Les noces for a very strange combination: two cimbalom, harmonium, percussion and a mechanical piano. I did that once in Paris out of curiosity for a concert performance — side by side — of the two tableaux and the final version for four pianos and voice (which was exactly the same in all the versions). It is extraordinarily difficult to have a mechanical piano with other instruments, because even if you want to be very strict, you know that you are never objective, because a mechanical piano is objective, and in spite of your desire to be as precise as possible, there is always a small difference between you and this mechanical device.

So that was for me proof that even if you are confronted with this kind of objectivity, you know how non-objective you are. What strikes me the funniest is that people who are most attached to this objectivity of interpretation call it “being faithful to the score” . . . but I don’t think that being faithful to the score is just reproducing it mechanically.

Now the opposite point of view is that a score is the most convenient and most appropriate way of notating what cannot possibly be freely notated. It means that the composer is aware from the very beginning that he cannot put down all the information he wants to give the performer — he knows that there are limitations and is perfectly aware of them. Many things can be notated very precisely, but a number of things are beyond notation, or notation would become so complex that it is useless. All notations — as precise as they can be, are just indications — the beginning of a process that leads to a higher level of understanding. Without this personal grasp of a score, you will play notes, but will never do justice to the work. This attitude is generally called “subjective interpretation.”

The danger here is that of falling into excess and distortion. Instead of serving the composer, you run the risk of using the music as a vehicle for ideas or feelings that are totally out of context. I don’t speak only about the exaggerated ego of the performer who wants to show that the composer was good but that he is even better. I’m not talking about that kind of showmanship, but I think that people who are honest with themselves often feel that, when they get into a work, they have to go farther than the notes because they know that the composer understands the limits of his notation — but they still think they are faithful to the composer. The worst thing in both cases is that everybody thinks he is more faithful than the next one! There is a tradition of performance that relies heavily on this highly individual treatment. I have compared the so-called objective performer to a kind of transmitter who does not change anything. Here you have a very different approach — you really have a translator. And when I use the word “translator,” I think of the Italian, which is “traditore,” and, as a matter of fact, there is a lot of treason in this kind of translation.

But is the difference between objective and subjective as clear as I have very schematically described it now? Is pure objectivity even possible without any interference of the personality? Can the transmission of musical data exist without any distortion? On the contrary, can musical notation — with all the consequences implied by phrasing, pace and so on — be ignored so that the intentions of the composer are distorted to the point of absurdity? The answer, of course, is very complex and does not depend only on the character of the performer, as highly individual as that can be.

Any performer or composer exists in relation to many factors not determined by himself. The period in which he lives, the countries where he was educated, the traditions he has absorbed during his years of apprenticeship, the historical views he has been taught — all make him extremely dependent. Everyone thinks he is an individual and has created his own world, but that’s absolutely not true — it’s impossible. I think Malraux once said, “You don’t learn painting by looking at the landscape; you learn painting by looking at other paintings.” And that is absolutely true for music. You don’t learn music just by listening to the winds or to any kind of natural inspiration — you learn music because you have heard some music, and you have been taught some music, and your education is absolutely essential in this process.

The composer or performer can follow the cultural patterns he has been given as models or he can rebel against what he has been taught. A person is shaped by a strong and coherent environment, and he will have to deal with that all his life, even if he is challenged by other cultures or approaches. You don’t remain where you were at the beginning. Speaking for myself, during the war, we were completely cut off and had a typical French education. But after the war, when the borders were open again — more or less gradually — we had the opportunity to explore German culture. And that was a gigantic opening for music as well as for painting. The music of the Second Viennese School — Berg, Webern, Schoenberg — was not performed at all in France, and it was the same for art — we had Picasso, Braque, Matisse, etc., and did not look to other things. And Klee or Kandinsky — who died in Paris after his years in exile — and Mondrian were absolutely ignored at the beginning. They came later, and Schiele and Klimt were completely unknown until very recently. So you can see that opening to other cultures in some circumstances is rather difficult. I am struck by the fact that, now, in Europe, every country looks for resurgence of individuality and identity, and we have again countries which are closed on themselves — there is not the kind of exchange that we had during the ’50s and ’60s. There is a kind of unease with other cultures, and it really is a big mistake if you’re not open to other cultures.

For me, one of the greatest moments of discovery, when I was about 20 years old, was to hear for the first time, on records, of course, the music of Asia; the sound was completely different. The culture of sound is terribly important for a musician, and the notion of time is so completely different from that of your Western culture that suddenly you experience something very important.

So the composer or performer facing a score has two categories of problems. The first one is of a very practical nature: what the writing of this music literally means, and for that he has to learn the language of signs for the classical components, vocabulary, syntax, etc. The second problem is more general: the relationship of a work to the history of music and what the signs of music mean stylistically.

The language of signs is relatively simple to learn. It depends, of course, to what extent you want to explore the specifics of the language. How pitch and rhythm are notated is easy to learn, even easier than dynamic or tempo markings, which are much less precise and more apt to be subjective. Because here, even at the roots of musical language, you find the contrast between objective, precise, numerical values and values that can only be approximate. A quarter note, for instance, is very easy to grasp; a quarter note is exactly two eighth notes and that 1:2 is a numerical value. It cannot be three, because if you have three, it will be a triplet and that is different and you know that. But in dynamics, forte is not twice a mezzo forte — two mezzo fortes do not add up to a forte. And the same thing for pitch — an octave is not twice a pitch. Of course, it is numerically, but not when you hear it; it’s perceived as another category. Therefore, musical language has very precise values — like pitch or rhythm — and very vague values, like dynamics and tempo. A scale of dynamics cannot be compared to a pitch scale — an accelerando or ritardando is subjective even between two metronome markings. As Schoenberg put it, rightly, I think, metronome markings are valid only for one bar and no more.

The more you go into the real meaning of musical notation, the more you see that what I call objective or numerical values are constantly submitted to subjective ones. Take rhythm, for example. Rhythm is accumulation of numerical values, such as 2 + 1, 1 + 2 + 2, 3 + 2, etc., which is a very precise relationship. But if you add a temp to that — even a fixed one — the proportion changes completely, and the numerical values are valid but related to a definite unit that determines the final value. And if the speed changes, then the numerical relationship is distorted, because in a hierarchy, the speed is stronger than the numerical relationship.

So even the most precise notation is subject to distortion. The basic numerical relationship in rhythm is subject not only to the tempo, but also to phrasing, articulation and dynamics. It is curious to see how the mind works when performing. You observe the numerical proportions, but at the same time, you modify them with your own understanding of the music. You may have very well-defined rhythmic values, but add phrasing that moves to a forte with an accent. This is a musical gesture and adds distortion, because you cannot perform the music without the gesture — that’s absolutely impossible. So with the gesture automatically comes distortion; it can be rather large, depending on the impulse you want to give, but it is there.

Now when we come to the idea of style, it is obvious that in what we call romantic music, where the pulse relies heavily on the emotional quality of the phrase, the tendency to distort the numerical value of rhythm is strong, to give it this emotional quality that it requires. In music that is essentially rhythmic — Stravinsky or Bartók, for instance — the basic pulse must respect the numerical values in a very strict sense, otherwise the essence of this music is gone.

Classical and romantic music are based on a regular meter, which rarely changes; you have 4/4 or 3/4 for entire movements. Of course, there are variations within this meter, but it is regular. So a musical gesture involves modifying the values within this meter — otherwise, we would have no musical gesture. But in music by Stravinsky, for instance, we have an irregular pulse that is based on two, such as 3-1-2, 1-2-3, 1-2, 1-2, 1-2-3, etc., and if you don’t respect that you lose not only the pulse, but the essence itself of the music.

***

To learn further the language of music, it is essential to be able to read, not only the line of a single instrument, like the violin or the flute, where you only need to know a line and to read in one clef. But if you want to read a score of chamber music, you have to learn the alto clef and the tenor clef and to synthesize three, four or five lines. With an orchestral score, you have much more than that — sometimes 30 or 40 systems — you are confronted with this large amount of information and have to read it, and that implies knowledge.

I think spontaneity can be propelled very strongly by studying the score; the flow of the music becomes natural to you and that is an experience you absorb. Now looking at a score, both before the performance and during the performance, for me is like a bicycle race. A cyclist first studies the map, and says, “There are 10 kilometers here that are very hard and further on there are 15 kilometers where I can relax, then I have five very hard kilometers and then it is downhill.” But if they are careful, they try out the course the day before and learn it with their muscles and their body, and that is exactly what you do with the score. You know it in your mind first. You study the score and then you have to educate your muscles along the score — it is a different set of muscles, of course, but exactly the same training.

Through study and rehearsals, you absorb a lot and become so familiar with the score that you don’t think very much — you have a spontaneous reaction. Your reactions are still planned, because you have thought them out, but as you become more familiar with the work, your instinct absorbs your culture, and I attach a great value to this acquired spontaneity. At a certain point, imagination and reality are one and the same thing, and I think that it is the ultimate goal of the composer as well as of the performer to be totally unified in the unique communion of the work. It remains an impossible idea, but every day we try to come nearer to this idea of unifying reality and vision.