In 2001, Warner Bros., a studio established during Hollywood’s golden era, launched one of the most important franchises in movie history, and in the process, helped to cement a pop-culture phenomenon. Drawing on the extraordinary literary work of J.K. Rowling, who created a mythological world as grand as “Star Wars,” but filled with more wit and humanity, the ‘Harry Potter” film series consolidated all of the advances in computer-aided animation and capitalized on fantasy and superhero craze of recent decades. Although the young wizard Harry Potter is nominally the hero, the series evokes the golden age of moviemaking, when vivid supporting characters crowded the canvas and compelling narratives captivated filmgoers’ imaginations.

In his four-star review of “Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone” (2001), film critic Roger Ebert lauded the film as an instant classic destined to be embraced by future generations of moviegoers. (The film opens this season’s CSO at the Movies series, with sold-out performances Nov. 25-27.) “Like ‘The Wizard of Oz,’ ‘Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory,’ ‘Star Wars’ and ‘E.T.,'” Ebert wrote, “it isn’t just a movie but a world with its own magical rules.”

BY ROGER EBERT

”Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone” is a red-blooded adventure movie, dripping with atmosphere, filled with the gruesome and the sublime, and surprisingly faithful to the novel. A lot of things could have gone wrong, and none of them have: Chris Columbus’ movie is an enchanting classic that does full justice to a story that was a daunting challenge. The novel by J.K. Rowling was muscular and vivid, and the danger was that the movie would make things too cute and cuddly. It doesn’t. Like an “Indiana Jones” for younger viewers, it tells a rip-roaring tale of supernatural adventure, where colorful and eccentric characters alternate with scary stuff like a three-headed dog, a pit of tendrils known as the Devil’s Snare and a two-faced immortal who drinks unicorn blood. Scary, yes, but not too scary — just scary enough.

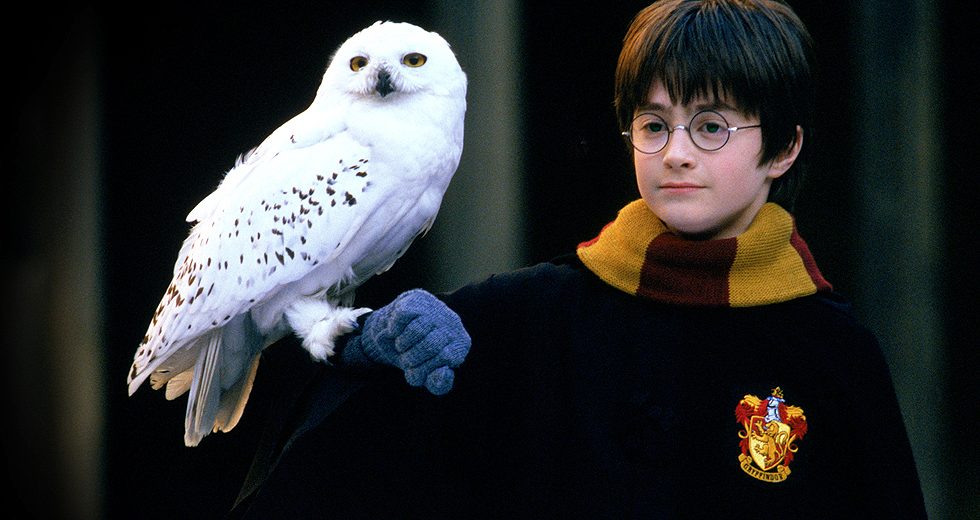

Three high-spirited, clear-eyed kids populate the center of the movie. Daniel Radcliffe plays Harry Potter, he with the round glasses, and like all of the young characters, he looks much as I imagined him, but a little older. He once played David Copperfield on the BBC, and whether Harry will be the hero of his own life in this story is much in doubt at the beginning.

Deposited as a foundling on a suburban doorstep, Harry is raised by his aunt and uncle as a poor relation, then summoned by a blizzard of letters to become a student at Hogwarts School, an Oxbridge for magicians. Our first glimpse of Hogwarts sets the tone for the movie’s special effects. Although computers can make anything look realistic, too much realism would be the wrong choice for “Harry Potter,” which is a story in which everything, including the sets and locations, should look a little made up. The school, rising on ominous Gothic battlements from a moonlit lake, looks about as real as Xanadu in “Citizen Kane,” and its corridors, cellars and great hall, although in some cases making use of real buildings, continue the feeling of an atmospheric book illustration.

At Hogwarts, Harry (Daniel Radcliffe, right) makes friends with Hermione Granger (Emma Watson) and Ron Weasley (Rupert Grint). | Photo: Warner Bros.

At Hogwarts, Harry makes two friends and an enemy. The friends are Hermione Granger (Emma Watson), whose merry face and tangled curls give Harry nudges in the direction of lightening up a little, and Ron Weasley (Rupert Grint), all pluck, luck and untamed talents. The enemy is Draco Malfoy (Tom Felton), who will do anything, and plenty besides, to be sure his house places first at the end of the year.

The story you either already know, or do not want to know. What is good to know is that the adult cast, a who’s who of British actors, play their roles more or less as if they believed them. There is a broad style of British acting, developed in Christmastime pantomimes, which would have been fatal to this material; these actors know that, and dial down to just this side of too much.

Watch Alan Rickman drawing out his words until they seem ready to snap, yet somehow staying in character. Maggie Smith, still in the prime of Miss Jean Brodie, is Prof. Minerva McGonagall, who assigns newcomers like Harry to one of the school’s four houses. Richard Harris is headmaster Dumbledore, his beard so long that in an Edward Lear poem, birds would nest in it. Robbie Coltrane is the gamekeeper Hagrid, who has a record of misbehavior and a way of saying very important things and then not believing that he said them.

Computers are used, exuberantly, to create a plausible look in the gravity-defying action scenes. Readers of the book will wonder how the movie visualizes the crucial game of Quidditch. The game, like so much else in the movie, is more or less as I visualized it, and I was reminded of Stephen King’s theory that writers practice a form of telepathy, placing ideas and images in the heads of their readers. (The reason some movies don’t look like their books may be that some producers don’t read them.) If Quidditch is a virtuoso sequence, there are other set pieces of almost equal wizardry. A chess game with life-size, deadly pieces. A room filled with flying keys. The pit of tendrils, already mentioned, and a dark forest where a loathsome creature threatens Harry but is scared away by a centaur. And the dark shadows of Hogwarts library, cellars, hidden passages and dungeons, where an invisibility cloak can keep you out of sight but not out of trouble.

During “Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone,” I was pretty sure I was watching a classic, one that will be around for a long time, and make many generations of fans. It takes the time to be good. It doesn’t hammer the audience with easy thrills, but cares to tell a story, and to create its characters carefully. Like “The Wizard of Oz,” “Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory,” “Star Wars” and “E.T.,” it isn’t just a movie but a world with its own magical rules. And some excellent Quidditch players.

Reprinted with permission of the Ebert Co. Inc.