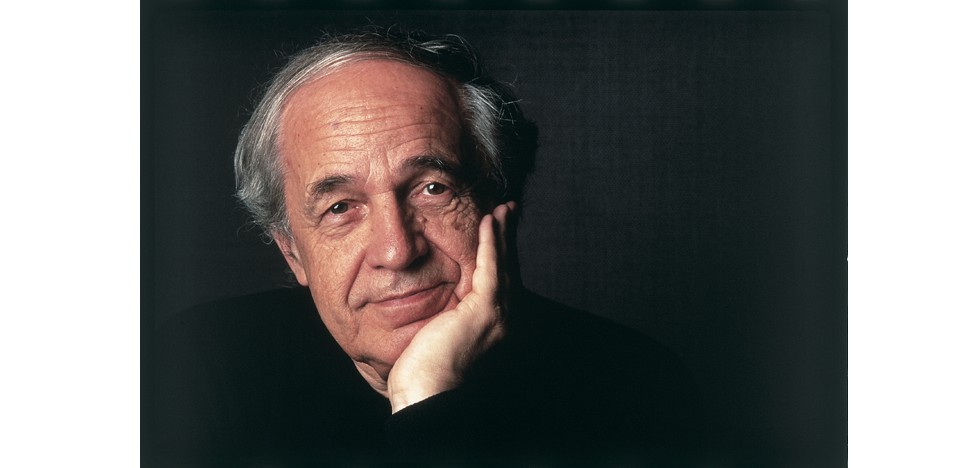

With the death of Pierre Boulez in January, one of the boldest chapters in the life of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra has come to a close.

Boulez played a unique and unusually powerful role in Chicago. As the CSO’s official conductor emeritus, unofficial éminence grise, and above all, beloved member of the family, his work with our musicians and his presence in our city encompassed so much more than any conventional title could suggest.

Boulez would have turned 91 on March 26. In recent years, he had often made it a point to spend his birthday with the orchestra. In 1999, he celebrated the day in Chicago in a most Boulezian way, leading the Chicago Symphony Orchestra and Chorus in Schoenberg’s formidable Moses and Aron.

We all put March 26, 2015, on our calendars, hoping to have him back in Chicago to participate in the many activities we had planned for his 90th birthday, but by then the man we knew as the very epitome of youthfulness — in the pace of his walk and the speed of his mind, his embrace of the latest in art and technology, his refusal to live in the past — was no longer well enough to make the trip.

Boulez first appeared with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra in February 1969, conducting music by Debussy, Bartók, Webern and his teacher Olivier Messiaen. “Boulez firmly believes in the classics of our century,” the Chicago Tribune critic wrote of the concert. “He is also immensely qualified to spread the word, possessing a composer’s mind, a conductor’s savvy and a poet’s soul.” At the time, Boulez was famous as a revolutionary composer, and by the time he began his annual residencies with the CSO in 1991, he was also recognized as one of the most revelatory conductors of his age.

In Chicago, Boulez soon became our guide to the modern classics, a restorer of repertory staples and our prophet of the new. Over the years, Boulez worked with the Civic Orchestra, gave a series of lectures at the Art Institute of Chicago, appeared on the CSO’s MusicNOW series and brought his Ensemble Intercontemporain to town — all in addition to his regular appearances with the CSO. In 1991, he began to make recordings with the CSO — an all-Bartók coupling of the Cantata profana and The Wooden Prince won four Grammy Awards, including one for best classical album. (Eight of his 26 Grammys are for discs with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra and Chorus.) He conducted the orchestra on tour in Japan in 1995, at the Berlin Festtage in 1999 and Cologne in 2000, as well in Carnegie Hall on several occasions. The CSO was one of just a handful of orchestras he conducted on a regular basis, and his close relationship with the orchestra, which grew and deepened over the years, became one of the high points in his career. This was an orchestra, he openly admitted, that he loved.

Boulez made his name as a conductor devoted to the great pioneers of musical modernism — Stravinsky, Bartók, Debussy, Schoenberg — the same composers who were his starting point as a composer. Those figures, along with Ravel and Mahler — a more recent fascination — were the ones he explored in the greatest depth with the CSO. Although we tended to think of Boulez as a specialist, during his Chicago seasons he conducted music by more than 30 composers, including revelatory Mahler (symphonies 1, 2, 4, 6, 7 and 9), blockbuster Berlioz (a complete Romeo and Juliet and the rarely heard Requiem), what many consider definitive readings of the big Stravinsky ballets, new classics (Berio’s Sinfonia and Ligeti’s Piano Concerto) and operatic landmarks of the 20th century (Bluebeard’s Castle by Bartók, preserved in a Grammy-winning recording, and Moses and Aron). But he also led music by composers not normally linked with his name — Haydn, Schubert, Dukas, Roussel, Szymanowski, Scriabin. In later years Chicago audiences saw Boulez’s interests move in unexpected directions: he led his first-ever performances of Janáček’s Glagolitic Mass and Bruckner’s Fifth Symphony here, both in 2000. And, of course, he introduced us to composers whose names were brand-new to us. It was always our privilege to learn, to explore and to listen, as he continued to spread the word.

Boulez last appeared on the stage of Orchestra Hall to conduct the orchestra and chorus in December 2010. In subsequent seasons, when his doctors would not let him travel to Chicago, programs that he planned and pieces he wanted to revisit had to go on without him. In 2014, A Pierre Dream, a Beyond the Score portrait of Boulez, brought him fleetingly back to us on video — offering reminders of the very sound of his voice, the clarity of his ideas, his wicked humor, his astonishing vision, even though his own eyes had begun to fail him. But it is in the adventuresome music we choose to play and the unconventional programs we plan, and in the lessons he taught us — to believe in the music of our own time, to embrace what lies just over the horizon — that his spirit will long live on in Chicago.

Phillip Huscher has been program annotator for the Chicago Symphony Orchestra since 1987.

Photo by Philippe Gontier