The Chicago Symphony Orchestra has a formidable history of playing Brahms’ four symphonies. The orchestra performed the Third Symphony in April 1892, on the final concert of its very first season, and Theodore Thomas, the Orchestra’s founder and music director, introduced the others, one by one, in each of the next three seasons. Both Thomas and his successor, Frederick Stock, placed Brahms’ orchestral music at the heart of the Orchestra’s growing repertoire. In fact, for eighty-three consecutive seasons, there was at least one symphony by Brahms featured every year.

Thomas was a pioneer in introducing Brahms to this country. By 1891, when he founded the Chicago Orchestra, he had been performing the composer’s music in public for nearly forty years—from the time Brahms was a completely unknown name in America. In fact, when Thomas made his New York debut as a violinist in 1855—he was just twenty at the time—performing chamber music with the brilliant young pianist William Mason, he played in the world premiere of Brahms’ B major piano trio, the first of the composer’s works to be heard in America, and the only one to be performed in the United States before it was given in Europe. Once Thomas decided to become a conductor in the early 1860s, fired by the idea of introducing the landmarks of orchestral music to the American public, he became Brahms’s most powerful champion in the United States.

In 1877, the year after the long-awaited premiere of Brahms’ First Symphony in Germany, Thomas and his chief rival, Walter Damrosch—the two most commanding conductors in New York at the time—fought over the chance to be first to play the work in this country. Thomas acquired the rights and announced the premiere for January 1878, but Damrosch outsmarted him and gave the U. S. premiere three weeks earlier. (According to the most popular account, a friend of Damrosch convinced Gustav Schirmer, Brahms’ U. S. publisher, to let him borrow the new score overnight for study purposes, and then delivered it to Damrosch’s house, where a team of copyists was waiting to work through the night to prepare the orchestra parts.) The New York press made much of the rivalry: after both men had led the symphony in New York that winter, one paper reported that in the third movement Damrosch conducted eighty-five beats to the minute and Thomas only sixty-four, implying, without musical logic, that Damrosch was the winner. Over the next several years, Thomas continued his campaign to introduce Brahms’ music to the American public; he gave the first U. S. performances of Brahms’ Piano Concerto no. 2 and Double Concerto in New York, and introduced the Variations on a Theme by Haydn in Boston on tour with his own orchestra.

By the time Thomas moved to Chicago in 1891 to start the Chicago Orchestra, he had already conducted all four of Brahms’ symphonies with the New York Philharmonic, and he clearly intended to play them regularly in Chicago. When he led the Third Symphony at the close of the first season, the press was encouraging. “Brahm’s [sic] Symphony is in every respect a masterly and a thoroughly delightful creation,” the writer for the Chicago Tribune reported, going on to call Brahms “a master who writes not merely because he would demonstrate his skill in the technique of composition, but because he has a musical message for the world.” But the Chicago public was not yet convinced. When Thomas was told that local audiences didn’t like Brahms, he is supposed to have shrugged and said, “Then I will conduct him until they do.” According to Thomas’s wife Rose, “there was no composer of any nationality for whose music Thomas did so much in this country, for he played the Brahms symphonies directly against the popular will every year of his life, until the public grew to understand and appreciate them in spite of themselves.”

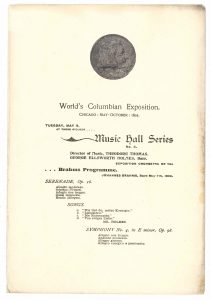

During his first season in Chicago, Thomas was named music director for the World’s Columbian Exposition, set to open in May 1893. Thomas intended to make music a central part of the fair’s activities, and he invited Brahms, who had never set foot in the United States, to appear as the White City’s honored guest. Brahms demurred. On September 1, 1892, he wrote to Thomas, saying he was greatly tempted but afraid he would back out at the last moment. “Kindly excuse, then, the old-country man who cannot undertake the long voyage so lightly as you do, and turn over to another of our colleagues the honor and pleasure of representing German music at the Exposition.” Dvořák ended up being the fair’s most famous visiting composer instead, and Thomas paid tribute to Brahms by leading a concert entirely of his works with the Chicago Orchestra in the first month of the Exposition. (An all-Brahms concert was highly unusual fare in those days.)

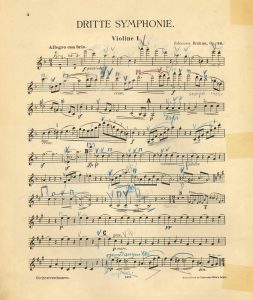

Despite Thomas’s efforts, Chicago was slow to warm to Brahms’ music. Even the local critics were largely indifferent or unimpressed. “The composer is tiresome to the degree of being almost unbearable,” the Chicago Times wrote in 1895. The Chicago Herald said, “his works, hardly without exception, are more for the musician and student than for the music-lover and nine-tenths of those who compose the average orchestral concert audience.” But when Brahms died, in April 1897, the Chicago Tribune mourned him as “one of the greatest, if not the greatest composer of music in the world.” The Chicago Orchestra played Brahms’ Third Symphony in his memory. On the program page, the piece was encased in a black box.

By then, the Chicago Orchestra had become America’s great Brahms orchestra, with a peerless champion in Thomas and with ties to the composer himself. Bruno Steindel, Chicago’s principal cello from the very first season, had played under Brahms in Berlin, where he held the same position with the Berlin Philharmonic for several years. Frederick Stock, who joined the Orchestra in 1895 as a violist—and would succeed Thomas as its music director—came to Chicago from the Cologne Orchestra, where Brahms was a regular visitor. (Stock would later make the Orchestra’s first recordings of Brahms’ music.) Thomas’s commitment remained undimmed: he took the Fourth Symphony on the Orchestra’s first tour to New York City, in March 1896, and the First Symphony was the centerpiece of the last program the Orchestra played at the Auditorium Theatre, in December 1904, before moving into its new home, Orchestra Hall.

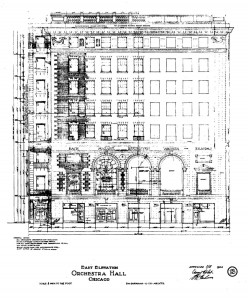

Even then, Brahms was still something of a controversial figure in Chicago. Early in 1904, as Daniel Burnham’s design for Orchestra Hall reached its final form, the names of five composers were incorporated just above the tall arched windows on the second floor. You can see them today, as you approach the hall: Bach, Mozart, Beethoven, Schubert, and Wagner. But one day in 2004, when I was looking over Burnham’s architectural drawings in anticipation of the hall’s centenary, I was startled to see a different lineup. On the official east elevation, which is signed, approved, and dated May 18, 1904, it is Brahms’ name that appears, not Schubert’s. Over the summer, someone got cold feet. On the final detailed construction drawings of the band course inscriptions, dated in September, Schubert takes Brahms’ place.

Was it too big a risk in 1904 to place Brahms’ name on the front of a concert hall that, as Burnham wrote, “will last for some centuries, for which reason its projectors feel it a duty and a privilege to build something that Chicago can love and be proud of more and more from generation to generation.” It is easy to imagine the thinking: Brahms hadn’t even been dead a decade; his music was still new, his place in the public’s affection uncertain. Schubert’s name would add two letters to the stone carver’s task but possibly save face in the long run. Yet, that season, when the Orchestra moved into its new home, it was Brahms who reigned on stage: Thomas programmed three of his symphonies and the Violin Concerto, in addition to the Haydn Variations and the Academic Festival Overture. The composer’s presence in Chicago’s musical life has not diminished since. Year after year, generation after generation, Brahms continues to sit at the heart of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra’s musical life: not one of the Orchestra’s 126 seasons has passed without Brahms’ music on its programs.

Phillip Huscher has been the program annotator for the Chicago Symphony Orchestra since 1987.