Two decades have passed since Russian pianist Boris Berezovsky last performed in Chicago. He will make his long-overdue return with a Symphony Center Presents Piano Series recital on March 25. “Finally!” he said from Moscow. “I was able to make it.”

Since winning the gold medal in 1990 at Moscow-based Tchaikovsky International Piano Competition, the same contest that launched Van Cliburn in 1958, Berezovsky has enjoyed a top-level international career. In 2006, he was named BBC Music Magazine’s instrumentalist of the year. But he has been largely absent from the United States since the late ’90s, because, as he bluntly explained, he “mismanaged” his career in this country. “And now, I want to start it again,” he said.

In a much-cited press quote, Gramophone magazine called Berezovsky “the truest successor to the great Russian pianists,” an allusion to the muscular style and affinity for big, romantic works typically associated with some of that country’s most celebrated keyboardists. The pianist does not shy away from this association. “That’s 100 percent what I represent,” he said. “I’m not Glenn Gould, that’s for sure.”

While he tends to stick to familiar repertoire, Berezovsky throws in a few twists along the way. Since the early 1990s, he has championed often-overlooked Russian composer Nikolai Medtner, organizing installments of the International Medtner Festival in 2006 and ’07. He’s also a big fan of Leopold Godowsky’s little-known Studies on Chopin’s Études, 53 arrangements of Chopin’s Études, which New York Times music critic Harold Schonberg called “the most impossibly difficult things ever written for the piano.” Berezovsky released an album of 11 of these arrangements, along with eight of Chopin’s original Études in 2005. “I think it’s one of my best recordings,” he said.

His most recent recording, released in January, features two familiar works — Brahms’ Piano Concerto No. 1 and Stravinksy’s Concerto for Piano and Wind Instruments — with an unusual approach. He plays both works alongside the Russian State Symphony Orchestra without a conductor. While it is not uncommon to perform Baroque era, Mozart and even early Beethoven concertos without a conductor, this practice is uncommon with later works because of the complexity and larger number of forces they require. But Berezovsky was not deterred.

“I have had this sentiment for many years that a concerto is chamber music on a big scale, and when you play quintets you don’t have a conductor,” he said. “So I tried to play the most difficult pieces without a conductor, and it works very well. I like the idea, so next season, I’m not playing with a conductor. I’m just playing with orchestras — any concerto in the existing repertoire. It’s all possible, and it functions very well. The orchestras love it.”

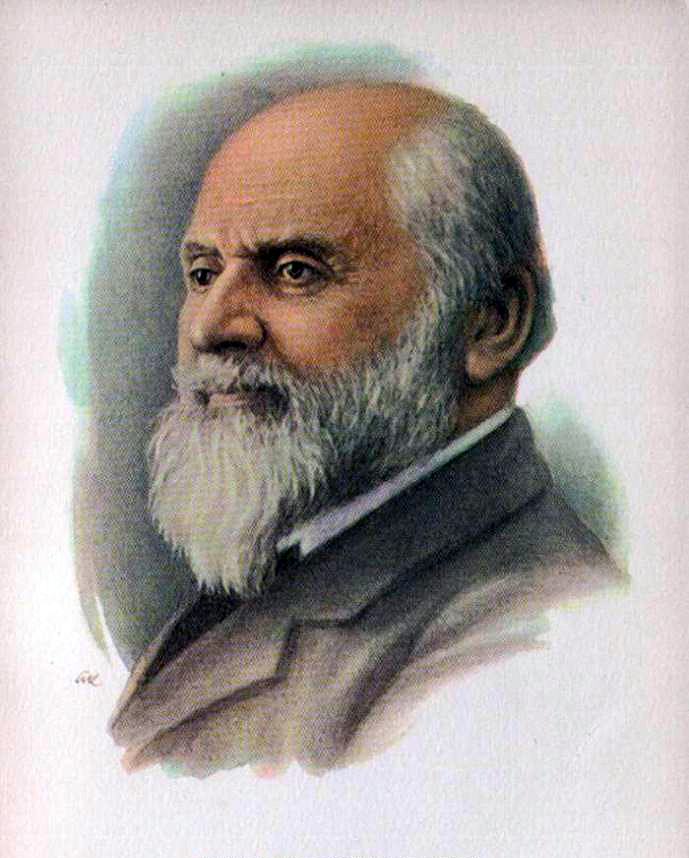

“His music is very neglected, and it’s very beautiful and difficult,” says Berezovsky of composer Mily Balakirev (1836-1910), whose works will be heard on his Chicago recital.

It might seem that Berezovsky would at least have to offer a few cues here and there during such performances just to keep everyone in sync. But he insists that he does not. “Nothing, not a single gesture,” he said. “During rehearsal, we just normally stop when something goes wrong, we fix it, and that’s it. We go on and play.” The big difference is that the orchestra musicians no longer see themselves as merely providing accompaniment but serving as equal partners with the soloist. “I don’t consider it accompaniment,” he said. “For me, it’s a symphony with piano. When this attitude changes, they [the musicians] are much more involved in the process than just accompanying. It gives much more pleasure to me and the orchestra players, and as a result, to the audiences.”

The biggest change Berezovsky has seen in the classical world is the scope of concert tours. Three decades ago, he said, such itineraries consisted of 15 or 20 concerts. “Nowadays, even three concerts they call a tour,” he said. “That obviously means classical music is becoming a little less popular, which is in itself is a contradiction of terms, because classical and popular are not necessarily the same thing.” When he comes to the United States for his recital in Chicago, Berezovsky also will be performing March 22 in the Kennedy Center in Washington, D.C. “You can call it a tour,” he said with a chuckle. “More than one concert is a tour.”

Originally, Berezovsky was set to play a more conventional program that included works by Chopin, Scarlatti and Prokofiev. But he switched to an all-Russian lineup, with no shortage of offbeat works. “It includes some pieces which are never played, and at the same time, it has all the standards like Rachmaninov’s Second Sonata and Scriabin’s Fifth Sonata, which are very well known. It’s a good mixture, and in terms of public relations, it’s much easier to promote Russian music by a Russian pianist rather than playing Copland.”

He will begin his recital with a group of works by nationalist composer Mily Balakirev (1837-1910). “Balakirev’s music is very neglected, and it’s very beautiful and difficult. It’s rarely played. He was influenced by Chopin a lot.” Also featured on the first half will be selected works by Antoly Liadov (1855-1914), who also fell under the spell of Chopin. “It’s very beautiful music,” he said. “He was one of the best miniaturists.” The rest of the program will consist of Scriabin’s Sonata No. 5 and some of his Études as well as Rachmaninov’s Sonata No. 2 and selections from 13 Préludes, Op. 32.

“So it’s a Russian program, basically,” he said with a laugh. “I would say 500 percent Russian, played by a Russian pianist.”

Berezovsky hopes his upcoming recitals in Chicago and Washington, D.C., will lead to more performances in the United States. “If it’s successful, which I’m pretty sure it will be, then, yes,” he said. “I regret not being there for so many years, and I’d like to have my sort of comeback.”