Less than two weeks after sensation Yuja Wang performs in Orchestra Hall with China’s NCPA Orchestra, another fast-rising pianist will take the spotlight in the venerable concert venue – Alice Sara Ott.

In 2010, replacing Lang Lang on short notice with the London Symphony Orchestra, Ott turned heads with her keyboard razzle-dazzle in Liszt’s Piano Concerto No. 1. Writing in the Guardian, critic Tim Ashley called it “the kind of gawp-inducing bravura performance of which legends are made.” And if not legends, certainly young careers. So it’s not surprising to find that line quoted in the first paragraph of the bio on the 26-year-old pianist’s website.

On Nov. 12-15, Ott will make her debut with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, performing with a guest conductor she has worked with previously — Pablo Heras-Casado. It will be her second appearance in Chicago since she presented a solo recital in June 2013 under the auspices of Symphony Center Presents, playing barefoot as is her custom. “Ott possesses dazzling technique and abundant power,” I wrote in a Chicago Sun-Times review, “but with her, it is never technical bravura for its own sake. Indeed, what was so impressive was how she was able to channel her obvious talents with such self-assuredness, maturity and élan, drawing an impressively nuanced tonal range from the piano and achieving a pleasing musicality every step along the way.”

This time she will present some of her first performances of Bartók’s Piano Concerto No. 3, as part of a program honoring the 90th birthday of Pierre Boulez, the Chicago Symphony’s Helen Regenstein conductor emeritus. Bartók died in 1945, leaving the work’s last 17 bars unfinished. His friend and pupil Tibor Serly completed the concerto based on musical sketches that Bartók left behind. Conductor Eugene Ormandy and the Philadelphia Orchestra presented the premiere on Feb. 8, 1946, with György Sándor as soloist.

Perhaps because it was intended to be a surprise birthday present for his pianist wife, Ditta Pásztory-Bartók, the piece is not as “extreme and abstract” as his earlier piano concertos,” Ott said. “It’s a beautiful concerto, and I love the way it starts and the interaction with the orchestra,” she said.

Even though Ott grew up in a home with a grand piano, she just kind of took it for granted at first. (Her Japanese-born mother had studied piano in Tokyo.) But all that changed when she was 3, when her parents took her to a piano recital, and the artist-to-be was immediately enraptured. Children, she said, are bursting with thoughts and emotions but don’t have the vocabulary to express them — a frustrating limitation. “So for me as a young child,” she said, “who was looking for something to be able express herself better, it was an incredible experience. I sat there and saw the people around me who were silent and they listened to this person on stage for two hours, and that impressed me a lot. I thought, if I would do the same, people would also listen to me for two hours without saying a word. I think it was a very simple desire for attention.”

Unlike some young musicians, who emphasize contemporary works, Ott has tended to program traditional pieces by time-honored composers like Beethoven, Liszt and Schubert. “I’m still in the process of discovering the old repertoire,” she said, “and there are still so many pieces I want to play, and that’s why I haven’t decided to stick with one composer or one era.” Her first teacher, a Hungarian, later inspired her passion for Liszt, but for the first few years of her piano studies, she played only the music of Baroque composer J.S. Bach. “Bach was my first love, and he will always be in a way a composer that I feel very close to,” she said.

Another piano teacher plunged her into the worlds of Beethoven, Schubert, Schumann and Mozart. But her affection for 18th- and 19th-century masters does not mean she is opposed to modern or contemporary music. She points out that she is playing Bartók in Chicago and cites her appreciation of György Ligeti, who died in 2006, and such living composers as Magnus Lindberg and Thomas Adès.

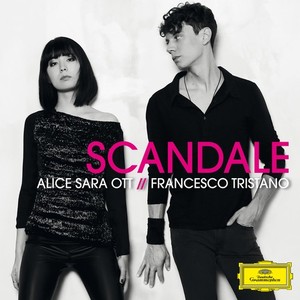

“Scandale,” which Alice Sara Ott recorded with pianist Francesco Tristano, was released this fall on Deutsche Grammophon.

Ott’s most recent recording, released in September, is “Scandale” (Deutsche Grammophon). Despite the seemingly provocative title, the release is not meant to incite its own scandal. Instead, it pays homage to Serge Diaghilev, an early 20th-century impresario who founded the famed Ballets Russes and shook up the cultural scene by recruiting the most avant-garde artists, composers and choreographers of the time. “For art, it was an incredible time,” she said, “because lots of things changed. He was a person who hated the Paris bourgeoisie, and he wanted to create something new and shock and provoke the people living in Paris and also give artists space and freedom to create something without being dependent on commercial success.” Among his most famous succès de scandale was the 1913 premiere of Le sacre du printemps, with its primitivistic choreography by Vaslav Nijinsky and primal, polyrhythmic music by Igor Stravinsky.

A two-piano version of “Sacre” is the centerpiece of “Scandale,” which Ott recorded with Francesco Tristano, a 33-year-old pianist from Luxembourg. The two meant four years ago, and first considered doing an album of Baroque double-piano repertoire. But that fell through, and their attention turned to the 20th century. “Of course, the literature for solo piano is much, much wider than for duo piano, but still there are lots or great pieces written for piano duet,” she said. “So we both wanted to do Le sacre du printemps. That was one of the first ideas that we both had, and then we were thinking: What could the story be, what could be the red line through the whole album?”

Also included on the release is a section from Rimsky-Korsakov’s 1888 symphonic poem, Scheherazade, which choreographer Michel Fokine adapted for a Ballets Russes production in 1910, drawing the protest of the composer’s wife. “Scandale” concludes with Ravel’s La valse, which was originally commissioned to be a ballet, but Diaghilev rejected it after hearing the two-piano version, saying it was “not a ballet. It’s a portrait of a ballet.”

Though just 26, Ott wants to pace her career. In 2011, she drew attention for a profile in London’s Telegraph newspaper that was titled: “Alice Sara Ott: ‘I don’t want to have burn-out syndrome.’” During the interview, she talked about the travails of traveling, saying, “I have realized I have my limits. I try not to say yes to everything. I don’t want to get to the age of 30 and have burn-out syndrome.”

Three years later, the pianist said she was close to a burn-out then, because she was playing more than 100 concerts a year. During one week, she recalls, she traveled to Asia twice, with a European concert in between. “I was lucky to experience that an early stage,” she said, “and I think I’ve learned from it.”

She now limits herself to no more than 60 to 70 concerts a year, taking an annual one-month break to spend time with friends and learn new music. “If you do such a job,” she said, “it is very important to know your limits and also be clear what your definition of happiness and career is. It is a very individual thing.”

Kyle MacMillan, former classical music critic of the Denver Post, is a Chicago-based arts writer.