Oxente menino! — sending messages through nonsense

João Pessoa’s concert hall pulses as the sun sets Sunday — Jurandir do Sax has competition tonight. PRIMA’s musicians, practiced and expressive, take stage shortly.

Several young women are in the large, open-air backstage, finishing banners for their mid-concert demonstration. The messages are blunt and defiant, denouncing violence against women. Cellist Natalia, who’s also part of the demonstration, has written a serious poem and hopes she has the strength to deliver it.

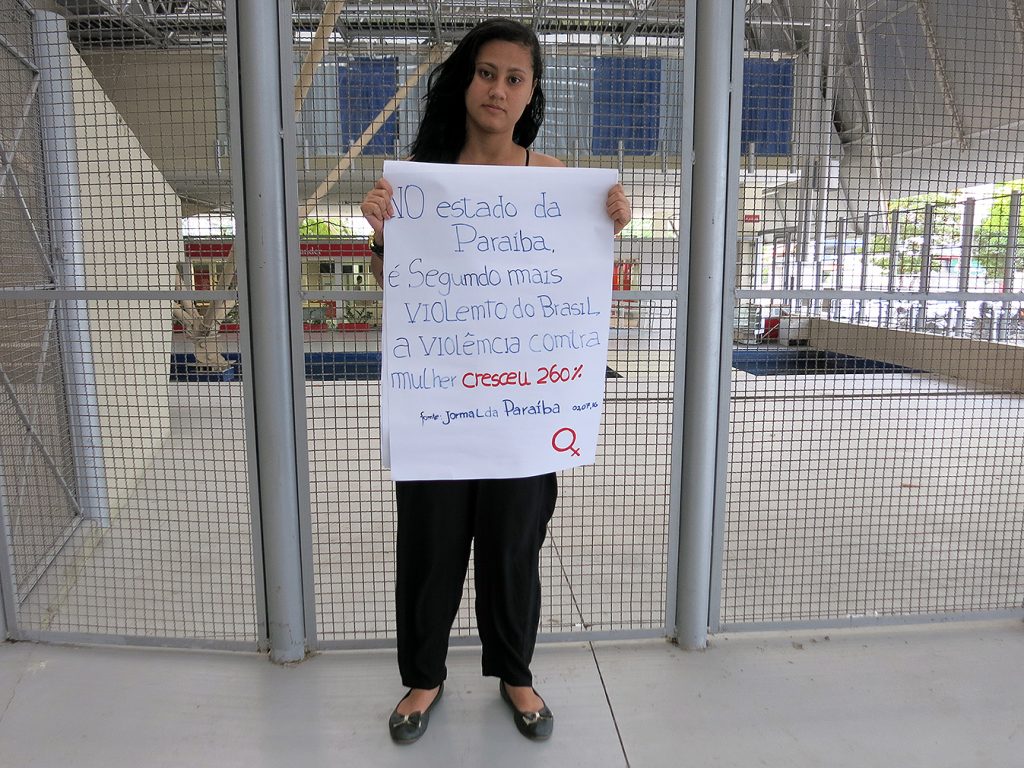

PRIMA percussionist Thamyres readies a sign that protests violence against women in Paraíba. | Photo: Andrew Huckman

The figurative instruments of change are ready, but the actual orchestral instruments still need plenty of attention. Vai estudar. Students are rehearsing everywhere, ripping through runs and repeating solos. Espedito, the father, edges near stage and attends to a promising horn player’s pre-concert needs — handing over water bottles and plying Espedito Júnior with lozenges. The son’s success is a family enterprise.

Anderson’s oboe is giving him fits. He’s corralled Alex Klein near the stage door while musicians slip past in concert finery as diverse as their Paraíba backgrounds. But Klein and Anderson are focused and concentrated; they don’t notice others.

There’s an open wooden case before them, with its contents carefully arranged. Gentlemen, choose a weapon. (Drawing knives in Paraíba is serious business.)

The furious whittling begins. Klein works with an elegant set of professional reeds that were just used to play Mahler at Ravinia and are headed back for Brahms next week. Several soak in a nearby glass. Klein plugs a shaved cane into his custom F. Lorée instrument, tosses off a quick, confident riff, then shifts the reed to Anderson’s Cabart — Lorée’s student model — where it gets a second, more tentative test.

Soak. Rinse. Repeat. Klein and Anderson shuffle reeds between them the better part of 10 minutes, with musicians already assembling onstage. Maybe Klein senses in Anderson an aspiration to artistry of emotion and sentiment — but right now it’s an aspiration urgently tempered by physical trip-ups and technical problems. The concert draws close and the rest of the players are depending on both men — the mentor, the student. This moment the two oboists understand each other most.

Klein hands over his own Lorée. It’s Anderson’s instrument tonight.

The concert’s on — a packed house — and Klein is in lateral motion again, “making a social point toward equality, which is at the base of what PRIMA is about,” as he suggested Saturday. Soon he’ll conduct the Strauss serenade, but right now he’s rushing around and resetting the stage, shifting chairs and kicking a conductor’s podium into place — everyone contributes, whatever the task, maestro included. A quick wave to the governor of Paraíba, Ricardo Coutinho, who’s front-row center. It’s off to the corner for a fast talk with teachers and to share encouraging words. There’s a chair reserved for Klein, double-wide near the side aisle, which the hall’s seating plan marks as “gordo” — big guy.

The side door opens, and the Strauss ensemble enters — Anderson carrying Klein’s oboe and the promise it invites, Espedito Júnior shouldering the hopes of his father, Klein wishing success for all of these talented young men and women.

PRIMA violist Danilo practices before the concert. | Photo: Andrew Huckman

The theater is full of encouragement and promise — the audience wants the kids to triumph — but Paraíba’s patriarchial character, whether as tradition or incitement, is never entirely distant. When Natalia and the women of PRIMA confront this crowd soon, what they’ll get back — whistles, acceptance or even indifference — is now a very immediate question.

The last Strauss notes fade away — Espedito Júnior’s warm tone on the horn finally earning Dad’s smile; an inspired Anderson, swaying with the emotional conviction of his oboe mentor, then peacefully still in the final gentle measures. Espedito Júnior’s state-inventoried brass (TH 1121984, chiseled on the bellpipe) and Klein’s custom Lorée, this night, are both instruments for change.

Seven women are about to invite change with their slogans. They enter in black concert dress and lift defiant banners in scarlet and black, Paraíba’s colors. The governor, in the front row, is silent, along with the audience.

Curiously, Natalia the poet and cellist is silent as well. Klein seems surprised a woman who’s written thoughtfully about the emotions of this evening chooses not to speak. PRIMA wants its students to involve themselves beyond musicianship, to voice their evolving convictions. Tonight Natalia should tell the crowd what matters most to her.

She will, she knows. But not yet.

“Rape is sick.” “My body is mine.” The messages on these signs would be forceful in any venue; here they verge on indictment. The seven fix their stares — stern Paraíbano visages for a new generation: these women witness, they endure, they demand understanding.

Forró, music of Brazil’s northeast, inspired PRIMA timpanist Maria Clara to become a percussionist. | Photo: Andrew Huckman

Applause. A standing ovation. A surprising collective conviction, onstage and in the crowd, that tough truths need airing. All of these Paraíbanos know what they wish they didn’t and respect what’s finally spoken. Seven women are showing courage, and everyone’s embracing them.

By now the night runs on its own energy. There’s nothing left to control or manage, because the students are stepping forward — musically involved, socially engaged — flipping concert-hall hierarchy on its head.

When Klein rises to conduct a final time — a pulsing danzón — he’s already irrelevant. The orchestra sees its maestro perched up front, but it’s feeling and following the drummer in back, who’s standing firm and staring him down.

These are Maria Clara’s rhythms and now she’s the one, not Klein, driving this ensemble. Her hair, bunched on Saturday, is let loose and flying about, strands crossing her face and tracing wild signatures his baton can’t match. There’s no wresting back control.

And so a proud Klein steps off the podium, mid-danzón, so Maria Clara and a hundred young Paraíbanos can have their musical way. He’s sitting up front near the gordo seat, pleased and smiling.

“What would be a good dream for an oboist?” Klein answered his own question Saturday. “I’m living. I’m living a good dream looking at these young people here. … I’m living a good dream when [the CSO’s Riccardo] Muti looks at me and smiles. And I look — wow! Maybe I can do this again. And then I actually do it.”

But Klein is done in João Pessoa tonight — sim, senhor! Best to get packing for Chicago. Here’s the governor with a valedictory and a medal — a statuette that’s half-bandit, half-padre (there’s no higher honor here). Right now it’s time for Paraíba’s mulheres macho to start running the show.

Priscila Santana, PRIMA’s new director, grabs the podium, and it’s her orchestra — their orchestra — from here on out. She’s speaking with the passion shared in the rehearsal Saturday — about growing, changing and working together — and the musicians start a spontaneous sway, like a hundred Kleins who realize what it means to share emotion with an audience, until it seems Santana’s remarks have already turned to music.

That’s when Natalia, the poet and cellist, steps up.

The more she fights tears, the stronger her voice emerges. Looking directly at Klein, she starts reciting:

You know who you are? You’re just a simple farmer! …

Look at your hands. Where are the scars and calluses that once made you proud? …

Sow, water, dream, believe. Even the seeds are dreaming, too.

And you know what? They’re blooming and flowering.

You’re that farmer, Alex. We’re those seeds.

Dry soil? Arid land? Impossible? No way?

Why not?

“Today we say goodbye. But it’s not really goodbye.” Natalia’s confident. “It’s just até logo — until next time.”

The strains of the “Mulher Rendeira” finale take speed, but this night something’s on edge and off-kilter, not at all like rehearsal. This isn’t a song about careful mending and weaving. It’s the spirit of spinning and a trust when threads unravel.

Klein surely knows he’s duped by his own ruse. The kids have grabbed his careful arrangement and ripped it into their own, wresting back the music a gaúcho maestro used to rope in nordestinos, co-opting it with their own spontaneity and meaning.

Do you really think we’d waste years and ride hours to wonder “What’s this nonsense?” Oxente menino! You taught us to bring music into our lives, to make strong civic choices and to courageously embrace opportunity whenever it appears.

So I’m going to dance with the governor!

A young trombonist spirals from the bouncing stage and grabs Governor Coutinho for a festive two-step forró. For “Mulher Rendeira,” Klein’s the prize, nabbed to dance by an insistent violist. (They even yank up a writer, who’s counting “um, dois … um, dois …” like it’s got a chance of helping.)

We’ve always been the ones running you, Alex. We’ve let you roam our close-knit state to sing and weave threads tight. But when we let the strands unravel, we know the fabric holds. We’ve been strong a long time, seen so much that’s tough and always pushed right through. That’s what we taught you when we roamed our roads together. Now get back to your own pathways and listen to us good.

The orchestra’s pitched for the finish, PRIMA’s defiant new generation of rebels and saviors, slamming “Mulher Rendeira” right back at Klein. This time what they shout has meaning, and they know, when he’s surrounded by a powerful orchestra, Chicago and Paraíba’s steadfast oboist shows the strength to get messages again.

A hundred strong, they holler: “Vai estudar, Alex!” Keep practicing.

Sim, senhor!

Andrew Huckman is a Chicago-based lawyer and writer.