From the music it plays to the sentiments of its members, an orchestra makes a powerful statement about patriotism. During World War I, the Chicago Symphony Orchestra’s very existence was on the line.

BY PHILLIP HUSCHER

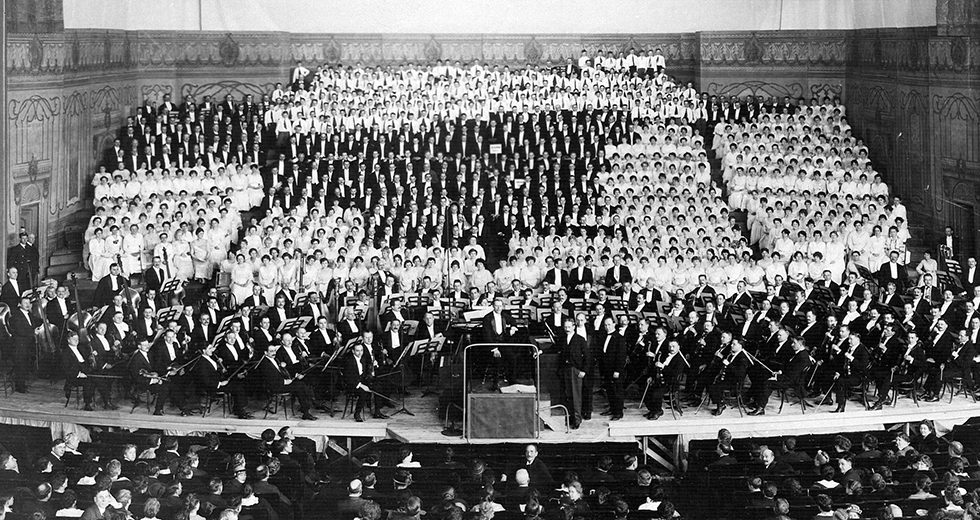

While he was in Munich during the summer of 1910, Frederick Stock, the second music director of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, heard Gustav Mahler conduct his monumental Eighth Symphony (The Symphony of a Thousand). “It made a tremendous impression on me,” Stock told The New York Times when he stopped over on his way home, and he said he hoped to program it in Chicago soon. It took six years of planning and some $30,000 to put in on the stage of the Auditorium Theatre, the only place in Chicago big enough to accommodate its forces—the Orchestra was expanded to 150 players, and in addition to eight vocal soloists, there were six local choruses and some two hundred boys from Oak Park and River Forest. The Chicago Tribune called it the biggest task of Stock’s career and “the most important event of its kind the West has ever known.” The entire week of performances in late April 1917—featuring five concerts, three of them devoted to Mahler’s symphony—was billed as a festival.

Then, on April 6, 1917, less than three weeks before the festival was to begin, the United States Congress declared war on Germany. At that week’s concerts, the American flag was draped over the back of the stage and the Orchestra played “America,” the audience singing to Stock’s conducting. The upcoming Mahler concerts had been expected to be what one critic called “the climax of Chicago’s musical season, for that matter, the climax of its musical life.” But the Auditorium wasn’t full for any of the performances. The American public now had serious matters to face, and few people wanted to hear an expensive monument of the Austro-German musical empire.

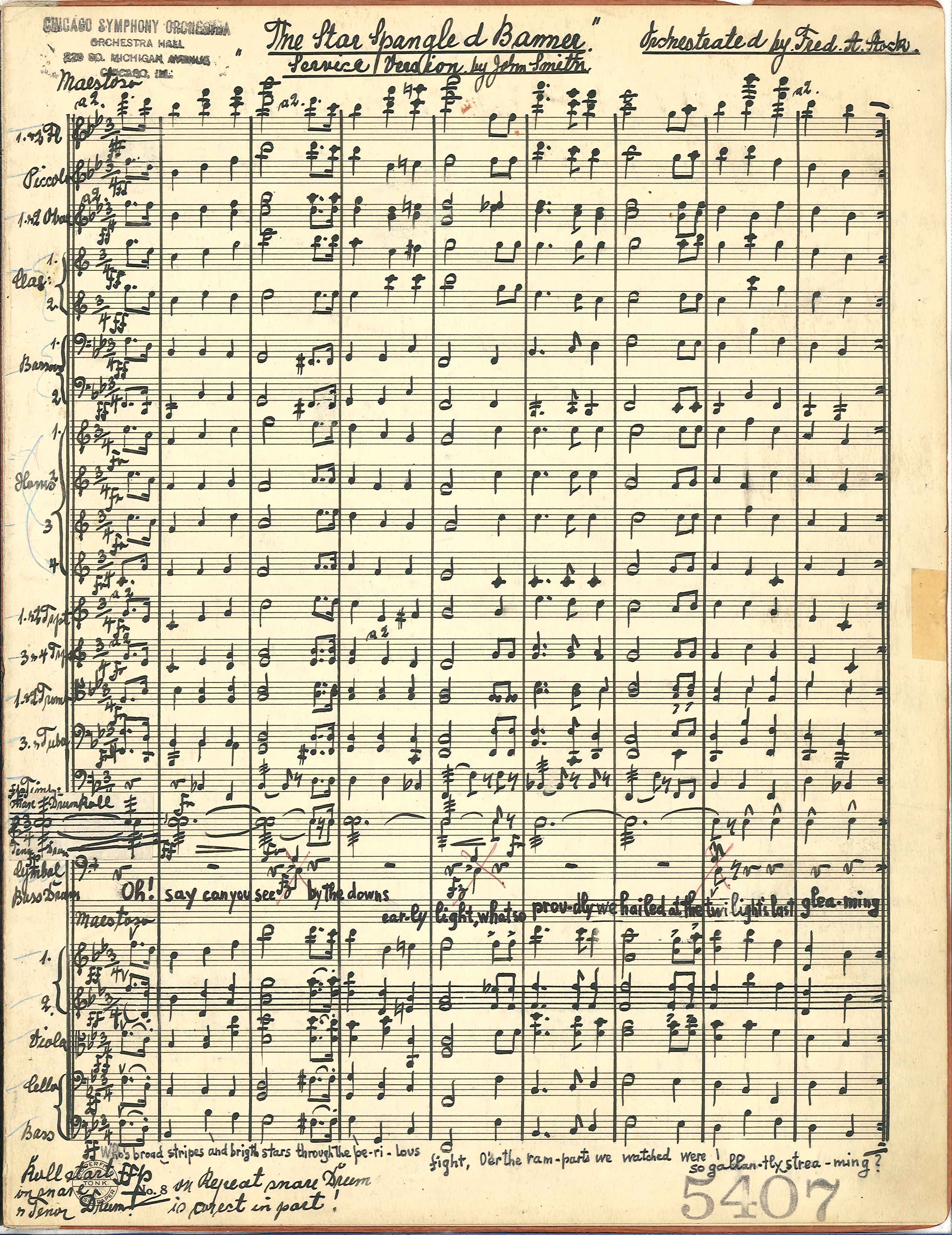

When Stock opened the following season on October 12, he began with “The Star-Spangled Banner” before moving on to Wagner’s Overture to Rienzi and Beethoven’s Pastoral Symphony—the kind of hardcore Germanic repertoire the Orchestra had favored since its first concerts. But that would soon change. Stock had already announced that every program of the new season would include at least one work by an American composer, and that each concert would begin or end with “The Star-Spangled Banner” or “America.”

At the end of the month, the Boston Symphony Orchestra’s manager Charles Ellis, with the support of BSO founder Henry Higginson, declined a request from several Rhode Island ladies’ clubs to perform “The Star-Spangled Banner” on tour in Providence. That decision made headlines across the country placing the unknowing, German-born music director Charles Muck at the center of controversy. “Muck ought not to be allowed at large in this country,” Theodore Roosevelt, the former president, said. “At this time, no man has any business to be engaged in any business that is not subordinate to patriotism. If the Boston Symphony Orchestra will not play ‘The Star-Spangled Banner,’ it ought to be made to shut up.” Muck resigned over the issue; he was subsequently arrested as a hostile alien and taken to an internment camp in Georgia. He never conducted in this country again.

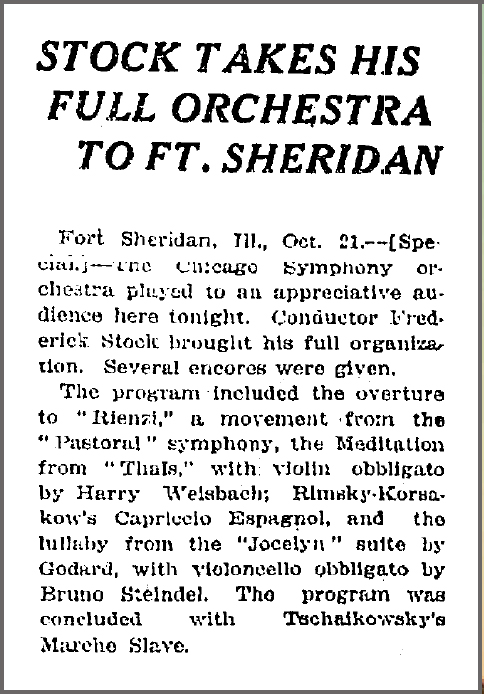

In Chicago, storm clouds were just beginning to gather. At the Chicago Symphony annual meeting in December, the Orchestral Association’s president, Clyde Carr, said that there had been rumors circulating about the patriotism of the Chicago orchestra. Of the nearly one hundred members, he said, there were only two players who had not taken out their final citizenship papers. “There is no orchestra in America more unimpeachable in its Americanism,” he said. The Chicago Symphony had been playing “The Star-Spangled Banner” regularly since the United States entered into the war. Stock’s weekly programming of American works was unparalleled in the United States (The New York Times later called it a “world record”). In October, Stock had taken the full orchestra to Fort Sheridan, north of Chicago, where it played a free concert in a hall packed with soldiers. The Orchestra had also become sensitive to what the papers called “enemy language.” Stock had switched to speaking English in rehearsals as soon as the war broke out in 1914, even though the Orchestra had conducted its rehearsals in German from the beginning, because so many of its members—and its first two music directors—were German born. (At the time, he had also told his musicians not to read German newspapers in public places.) Titles of certain compositions that had always been given in German were now listed in English in program books, on placards, and in newspaper ads.

In the afternoon on April 6, 1918, the members of the Orchestra met to draw up a series of resolutions affirming their loyalty to the United States. Charles Hamill read the resolutions to the audience at that night’s concert, pronouncing the Orchestra faithful to America “from the conductor to the kettle drum.” But that same week, word began to spread that Stock was not technically an American citizen: he was a German by birth, and therefore still a subject of the kaiser. The issue was that he had applied for his first U.S. citizenship papers four days after he arrived in this country in 1895, but he neglected to complete the process. By 1916, when the trustees asked him to finalize his citizenship to stave off concerns over his German heritage, he discovered that his 1895 application was invalid, and so he had to begin all over again—a process that could take two years.

The papers had a field day with the news. The Musical Courier, a respected national trade magazine, said that printing this story at this time was “a cheap, tactless, and vulgar piece of journalism, on a par with the character of those who perpetrated it.” Stock’s personal statements and artistic actions, the Courier continued, proved that he was “thoroughly, sincerely, passionately American in his aspirations, ambitions, and national spirit.”

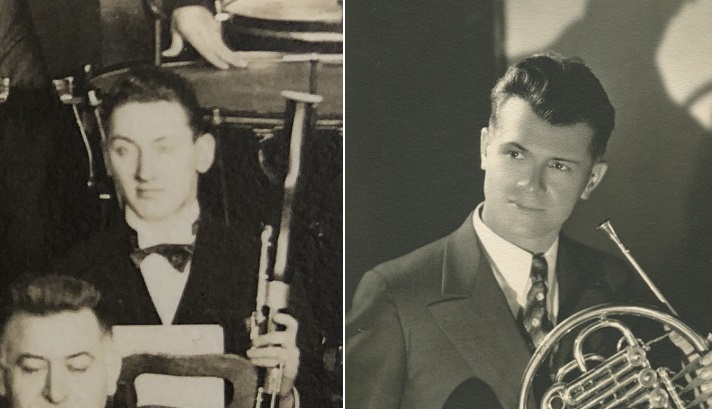

At the last concert of the season, a new flag was placed on the stage of Orchestra Hall. It was crimson and white, with two blue stars representing two members of the Orchestra, Walter Guetter, a bassoon player, and William Hoss, a horn player, who were now in training at the Great Lakes Naval Station north of Chicago. At the end of the concert, the audience remained on its feet after singing “The Star-Spangled Banner,” and did not leave until Stock was recalled to the stage and given a fanfare by his players. The Orchestra’s first full season in wartime ended in a rush of patriotic fervor. But the real storm had not yet broken.

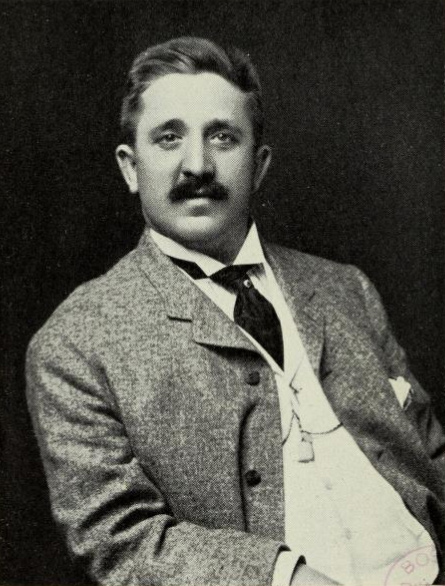

Bruno Steindel

On August 6, while the Orchestra was giving concerts at Ravinia Park, seven members were served with notices to appear before assistant district attorney Francis Borrelli the next day and answer charges that they had made pro-German statements. The papers reported that all seven were said to be enemy aliens. No names were released, but over the next few days, Borrelli grilled several men, including the Orchestra’s manager and trumpet player, Albert Ulrich. Attention centered on Bruno Steindel, the principal cello, who came to Chicago from the Berlin Philharmonic at the invitation of Theodore Thomas, the Orchestra’s founder, and had played in the ensemble since its first concert in 1891. He was said to have expressed his disloyalty many times and in different ways, and was accused of singing obscene words to the “The Star-Spangled Banner” as it was being played.

There were accusations against other players—some damaging, others less consequential—all of whom made emphatic denials. Borrelli claimed the evidence against Steindel was sufficient to warrant his denaturalization, which would lead to his imprisonment as an enemy alien. Day after day, throughout the hearings, Ulrich, who had been a U.S. citizen for forty years and had a son in the navy, stood by his musicians and claimed he had never heard any disloyal talk among the members of the Orchestra.

On August 14, the Chicago musicians’ union announced that all musicians who were subjects of the kaiser, including all men who had not been naturalized, would be dropped from the union’s membership. Stock, who was away in the Adirondacks, would also now be investigated as an enemy alien, the union said. “It would be a regrettable extremity,” Borrelli concluded, “to disorganize the Orchestra and deprive Chicago of the musical wealth it represents, but if it is proven to be pro-German, by all means sacrifice it.”

Following the Orchestra’s afternoon rehearsal on August 16, Ulrich called a meeting of the musicians. He gave them a good heart-to-heart talk and laid down a series of rules to follow—don’t speak German in public, don’t make thoughtless remarks, don’t forget that it is every man’s duty to be loyal to America. The charges against Steindel, he said, were born of professional jealousy and plainly instigated by a man who wanted Steindel’s job. The Orchestra’s members then pledged their loyalty, and all German-born musicians publicly renounced the kaiser and the fatherland. That same day, the union decided to drop its threat to oust enemy alien members. But the next day, in Merrill, New York, Stock wrote to the trustees with his resignation.

Before Stock’s letter reached Chicago, Orchestral Association president Carr called a meeting of the trustees to put an end to the idle and malicious gossip about the loyalty of Orchestra members. They unanimously adopted a resolution to fully cooperate with the Department of Justice’s examination and to express their confidence in the musicians’ patriotism. The trustees stressed that the Orchestra would not fold under any circumstances and that Stock would continue as its leader.

“My devotion to and love for this country I count among the finest assets of my inner self,” Stock wrote to the trustees by hand in his careful, even script in his letter of resignation. He went on to explain how he had failed to complete his citizenship papers, never once thinking that anyone would question that he was an American, “at heart, in thought, and in spirit”—as willing as any patriot, as he put it, to give his blood or his last penny to the land that had adopted and embraced him. But he also now knew, he wrote, that many in the music-loving public could not read the sentiments of his heart or distinguish him from those who were, in fact, genuine enemy aliens. He had no choice, he concluded, for the sake of the Orchestra’s future and out of respect for its trustees, but to resign until he was officially granted full U.S. citizenship.

Eight trustees weighed Stock’s letter, line by line, and reluctantly agreed to release their music director. Eric DeLamarter, who was well known in Chicago, was quickly named assistant conductor and would temporarily take Stock’s place on the podium. At the same meeting, the trustees accepted a letter of resignation from Steindel.

The day before the new concert season was to begin, the Chicago Federation of Musicians announced it was expelling Steindel and three other Orchestra members from the union for alleged anti-American remarks. In the end, more than ninety witnesses had been called, the union reported, including Stock and every member of the Chicago Symphony. When DeLamarter walked on stage on October 11, to lead “The Star-Spangled Banner” and launch the new season, those four musicians were missing. There were a noticeable number of unused seats for an opening concert. The box office reported that sales had sagged since news of Stock’s resignation.

Before he resigned, Stock had programmed the new season’s first three weeks of concerts, and he had been careful to include just one work by a German composer, a concerto by Beethoven. (In San Francisco, the orchestra’s music director, Alfred Hertz had banned all music by living German composers; in Boston, Charles Monteux, who was temporarily in charge until Muck’s replacement was named, refused to conduct music by Wagner or Richard Strauss. The Metropolitan Opera had already decided to boycott Wagner’s operas the previous season.) But there was no escaping the Chicago orchestra’s ties to Germanic music. The day after the season opened, when more than 100,000 people marched through Chicago’s Loop in a Liberty Loan parade, Major General Thomas H. Barry entered the reviewing stand on the steps of the Art Institute and looked out across the street toward Orchestra Hall, with the names of Bach, Mozart, Beethoven, Schubert, and Wagner spread across its façade.

A month later, the Armistice was announced. That week DeLamarter led the Orchestra in Beethoven’s Eighth Symphony, with “The Star-Spangled Banner” at the top of the concert and “America” at the end. It was a program that was patriotic and restorative. The orchestra that many considered America’s greatest was back in its full glory, reflecting victory and peace in a way that only music can. But there was still one person missing from the equation.

On February 7, 1919, Stock appeared at the Chicago circuit court. He removed his hat, raised his right hand, renounced the German government, and swore “to make this his country, this flag his flag.” Ninety days later, he would at last be a U.S. citizen. On February 19, the executive committee voted to ask Stock to resume his position as music director beginning with the concert on February 28.

That day, the members of the Orchestra were applauded as they took their places on stage, but when Stock appeared and picked his way through the players to get to the podium, the audience rose and cheered. He spoke briefly, hanging on to the railing of his conducting platform, with words of thanks to all those who had stood by him during the past months, and to the players for their sense of duty at a time that could so easily have broken the Orchestra irrevocably. The last work on the program was his own composition, written for the occasion, the March and Hymn to Democracy. The piece is little more than a stirring display of patriotic fireworks, but Stock made his point. And he made it with music.

Phillip Huscher is the program annotator for the Chicago Symphony Orchestra.

TOP: Frederick Stock, Chicago Symphony Orchestra, and combined forces onstage for Mahler’s Symphony no. 8 at the Auditorium Theatre on April 24, 1917 | Photo: Rosenthal Archives

Note: A Time for Reflection—A Message of Peace—a companion exhibit curated by the Rosenthal Archives of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra in collaboration with the Pritzker Military Museum & Library—will be on display in Symphony Center’s first-floor rotunda from October 2 through November 18. The exhibit is presented with the generous support of COL (IL) Jennifer N. Pritzker, IL ARNG (Retired), Founder and Chair, Pritzker Military Museum & Library, through the Pritzker Military Foundation.