Scholars, historians and music lovers have long pondered the correlation and connection between a composer’s life and musical works. The curiosity comes naturally, since music is a universal language and an incredible medium for expression. Furthermore, there’s often a desire to understand the music and composers we love. To increase the complexity of this issue, instrumental music of course is wordless; that aspect perpetuates its lack of specificity and concrete meaning. Olivier Messiaen’s Quartet for the End of Time, which cellist Yo-Yo Ma and CSO members will perform May 17 in an SCP Chamber Series concert, has sparked great analysis, since it was created under some of the most dire conditions known to man. The French composer, who served as a nurse during World War II, wrote the chamber work while imprisoned by the Nazis.

Messiaen began his duties serving France in 1939, and in 1940, was captured by the Germans and held captive at a Nazi prison camp just outside Nancy. Later, he was moved to a more established camp in Görlitz, Silesia, called Stalag VIII-A (now part of Germany). It would be easy to assume that Messiaen’s Quartet for the End of Time (Quatuor pour la fin du Temps) is a piece that reflects the violence and oppression he undoubtedly experienced while being held prisoner. That isn’t the only story this quartet can tell, however.

As a prisoner, Messiaen defied logistical as well as emotional and spiritual odds. He was able to obtain manuscript paper from a guard, and befriended other musicians in the camp. In Nancy, he had met clarinetist Henri Akoka and cellist Étienne Pasquier, who would later premiere his Quartet for the End of Time, with Messiaen himself playing piano. The composer also met violinist Jean Le Bouaire, and these friendships inspired him to continue composing. With the musicians available, he created a quartet featuring atypical instrumentation for a 20th–century chamber work: clarinet, cello, violin and piano.

Beyond its unusual instrumentation, Quartet for the End of Time bears colorful marks that stamp the work as undoubtedly Messiaen’s. The self-professed “composer rhythmist” used blunt, syncopated rhythms throughout the eight-movement piece. While he often scored the instruments to play together in transparent unisons or octaves, the piece also features dense chords consisting of eight notes all sounding at the same time. Only four of the eight movements involve all four players; extended solos invite the ear to consider the quartet’s intriguing structure.

When French musicologist Antoine Goléa interviewed Messiaen about the quartet’s premiere, he described the dramatic experience: “An upright piano was brought into the camp, very out of tune, the keys of which seemed to stick at random. On this piano I played my Quatuor pour la fin du Temps, in front of an audience of 5,000 — the most diverse mixture of all classes in society — farmworkers, laborers, intellectuals, career soldiers, doctors and priests. Never have I been listened to with such attention and such understanding.”

German writer Hannelore Lauerwald interviewed cellist Étienne Pasquier, who relayed a very different account: “The first performance of the Quatuor took place in the hut that we used as the theater. All the seats were taken, about 400 in all, and people listened raptly, their thoughts turning inward, even those who may have been listening to chamber music for the first time. The concert took place on Wednesday, Jan. 15, 1941, at 6 in the evening. It was bitterly cold outside the hut, and there was snow on the ground and on the rooftops. Messiaen repeatedly claimed that there were only three strings on my cello, but in fact I played on four strings.”

Despite discrepancies in detail, both accounts recall audiences greatly moved by the musical experience. The camp’s newsletter even reviewed the quartet: “It was our good fortune to have witnessed in this camp the first performance of a masterpiece. And what’s strange is that in a prison barracks we felt just the same tumultuous and partisan atmosphere of some premieres: latent as much with passionate acclaim as with angry denunciation. And while there was fervent enthusiasm on some rows, it was impossible not to sense the irritation on others. The last note was followed by a moment of silence which established the sovereign mastery of the work.”

It is easy to think Messiaen’s Quartet for the End of Time expresses violence and feelings of constraint, and it likely does. The distinctive instrumentation and melodic combinations, accented rhythms and lack of stable tonality all point toward a piece expressing injustice and anger. But Messiaen’s fascinating identity extended beyond that of composer and musician; he was also a tremendously devout Catholic. At one point, the clarinetist from his prison quartet reportedly asked Messiaen to escape with him, but the composer declined, replying, “No, it’s God’s will I am here.” This account introduces an entirely new meaning to the Quartet for the End of Time.

One of Messiaen’s most poetic and poignant quotations affirms, “My faith is the grand drama of my life. I’m a believer, so I sing words of God to those who have no faith. I give bird songs to those who dwell in cities and have never heard them, make rhythms for those who know only military marches or jazz, and paint colors for those who see none.”

Perhaps his quartet also served as an act of faith, a symbol of camaraderie toward his fellow prisoners, or an oath to God that he would not give up, no matter the challenges.

Composers’ works are not limited or defined by the life circumstances in which they were created. Rather than debate the quartet’s meaning and how Messiaen’s life circumstances relate, perhaps this piece, which could be readily considered as tormented and angry, invites the listener not to search for one true meaning, but to delight in the knowledge that even in darkness, even in imprisonment, beauty prevailed.

Laura Sauer is a marketing associate for the Chicago Symphony Orchestra.

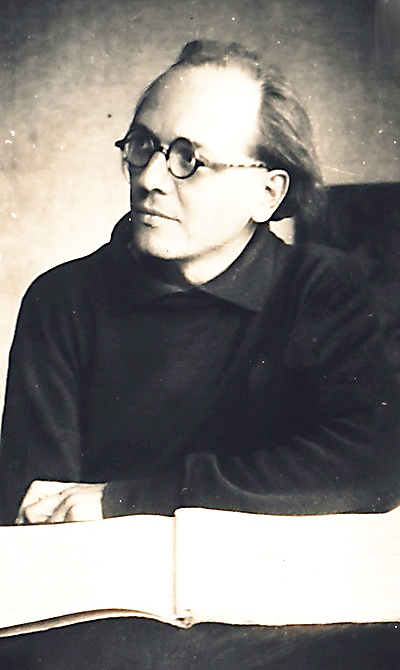

TOP: A prisoner orchestra at Stalag VIII-A in Goerlitz, Silesia (now Germany), with Ferdinand Carrion, a Belgian musician and prisoner-of-war, conducting. | Photo: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of Sonia Beker