Max Raimi, a longtime member of the the CSO’s viola section, started composing when he was a little boy. He was, he readily admits, no child prodigy.

“My first piece was for piano when I was 8 years old,” said Raimi who joined the Chicago Symphony Orchestra in 1984 after studies at the University of Michigan and The Juilliard School. “It was terrible.” (By age 8, Mozart, the very definition of a precocious musical genius, had already composed 10 piano pieces, 12 violin sonatas and a symphony.)

Raimi was inspired by one of Leonard Bernstein’s Young People’s Concerts, a popular series of programs televised on CBS between 1958 and 1972 featuring the New York Philharmonic with Bernstein, its charismatic music director, explaining various aspects of music making in simple terms.

“I was taking piano lessons, and Bernstein was talking about intervals [the spaces between any two given notes on the musical scale],” he recalled. Raimi then hummed his maiden effort, a laborious trudge up the scale in a series of meticulously even jumps. “I’m sure my parents were as encouraging as they could be,” he said with a laugh.

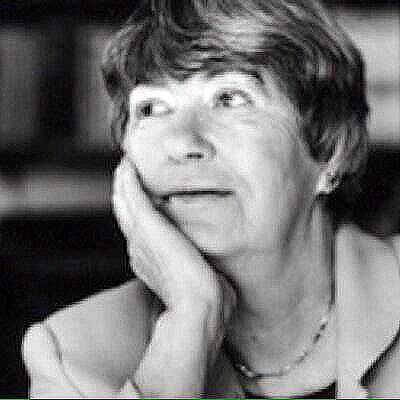

Lisel Mueller. | Photo: Tom Maday/Poetry Foundation

Though Raimi became a professional violist, he continued to compose. The CSO will give the world premiere of his latest work, Three Lisel Mueller Settings for mezzo-soprano and orchestra, on its subscription concerts March 22-24, conducted by Riccardo Muti. Elizabeth DeShong will be soloist in Raimi’s arrangement of poems by contemporary poet Lisel Mueller. The work was commissioned by the Poetry Foundation for the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. The program also includes the overture to Carl Maria von Weber’s opera Oberon and Schubert’s Mass in E-flat Major.

Born in 1924 in Hamburg, Germany, Mueller and her family fled the Nazis in 1939. They landed in Indiana, where Mueller’s father became a professor at the University of Evansville. After undergraduate studies in Evansville, Lisel did graduate work at Indiana University. A longtime Chicago-area resident, she has written steadily, and collections of her poetry won the National Book Award in 1981 and the Pulitzer Prize in 1997.

Until stumbling upon Mueller’s work, Raimi wasn’t much interested in poetry. “My dad used to make us recite poems at the dinner table, Browning and Tennyson, stuff like that,” he said. “I’d try to read a poem every week. I’d read it aloud, but I’d never know what [the poet] was doing. I would never get it.

Twenty years ago Raimi read about Mueller’s Pulitzer Prize in an article that included one of her short poems. “I got it immediately,” he said. “I couldn’t stop thinking about it for days.”

Raimi bought the award-winning book, Alive Together, and “devoured” it. He bought copies for friends, and in 1998, composed Settings of Four Lisel Mueller Songs, which was performed on one of the CSO’s MusicNOW contemporary chamber music concerts.

“There were always images from her poetry that haunted me,” Raimi said. ”It was a view of the world that was tragic, and at the same time full of hope, and at the same time understanding of great complexity. She’s not a native English speaker, but there’s something about her use of English that gives the language a power and an unvarnished quality that I just love. She’s very conscious of whether she’s using English words that come out of Romance languages or ones that come out of Anglo-Saxon German.”

Her writing, said Raimi, reminded him of the powerful voice of Mike Royko, a fabled Chicago newspaper columnist who wrote hard-hitting portraits of everyday life and everyday people from the mid-1960s to the mid-1990s. Royko won a Pulitzer Prize for commentary in 1972. “This is a weird comparison, but it’s like when I read a really good Mike Royko column,” Raimi said. “It was like a punch in the gut. There was nothing ornamented or extraneous about it.”

Though he has worked with some of the world’s great artists and played some of the world great music with the CSO, Raimi has never lost the drive to compose. He has written more than 60 works since 1981, stretching from arrangements of tunes like “Take Me Out to the Ballgame” and variations on the theme from “The Flintstones” cartoon TV series to a quintet for tenor sax and strings.

“I’ve always kept it up,” he said. “I get these ideas in my head, and I want to hear what they sound like. And I’ve always had musician colleagues who were generous with their time, and they’ve always inspired me.”

Among them was American violinist Gil Shaham, who surprised Raimi by playing one of his etudes as an encore after performing the Mendelssohn Violin Concerto with the CSO last fall. Titled Anger Management, the piece is a fiercely virtuosic etude Raimi wrote several years ago for solo viola and later transcribed for violin. Shaham played it onDec. 2 after the third of his four Mendelssohn concerto performances in Symphony Center.

“When Gil was in town,” said Raimi, “I figured I had nothing to lose, and gave him the music to one of the etudes. This was on Thursday night. To my astonishment, he learned it and was able to perform it brilliantly by Saturday. Some of these guys are just a different species than I am.”

Wynne Delacoma, the classical music critic of the Chicago Sun-Times from 1991 to 2006, is an arts journalist and lecturer.

TOP: Max Raimi, a longtime member of the CSO viola section, has written Three Lisel Mueller Settings, which will have its world premiere in CSO concerts March 22-24. | Todd Rosenberg Photography