Earlier this month, Max Raabe and his Palast Orchester glided through their winter residency at Berlin’s Admiralspalast, the 1910 theater that lends the band its proud moniker. Steps from the Friedrichstraße railway station, once the split capital’s Cold War border, Admiralspalast seems the stronghold of the singer’s whole career — and the fulcrum on which the city’s dynamic, turbulent cultural century still so often pivots.

What the debonair baritone gleans from German flea markets and song sheets around the world always makes its way back to Berlin, Raabe’s home since student days — a reminder that the jazzy melodies and tinged lyrics of the Weimar Republic (1919-33) were as much about what burrowed its way into the capital as the sounds that emanated from its stages.

The Palast Orchester’s current tour, “A Night in Berlin,” which swings April 8 into Symphony Center, celebrates Raabe’s foraging at, of all places, the Chicago Public Library. He recently spoke by phone about how a 1930s Jerome Kern foxtrot drifted out of Chicago’s stacks and into Berlin’s Admiralspalast and how that theater reflects Raabe’s family history, his musical growth and an ever-evolving Berlin that’s always glancing backward.

Chapter 1: Kern’s “I Won’t Dance” shimmies off Chicago’s shelves

Raabe: We spent the whole afternoon in the [Chicago] library and found maybe 10 or 12 original arrangements from that time and one of the pieces was “I Won’t Dance.” We were [rehearsing] on tour and figuring out how these arrangements worked, and then we started playing “I Won’t Dance” — it was in Boston. Suddenly the cleaning women in the theater started dancing, and we realized how well these arrangements worked and how brilliant this number still is.

These arrangements are written for many instruments but you have to choose which instrument is playing which tune and melody. There is a lot of material and you have to create your own orchestral version, but this is the second step. The first step is we saw that the cleaning women started dancing.

Our arrangement is the best we could find. Really — it is wonderful. We just taped it in Berlin, where we made a CD and DVD in the Admiralspalast.

At the Chicago Public Library: “I Won’t,” I Don’t” and “I Can’t.” The library’s Balaban and Katz Collection rescued thousands of the theater chain’s dance-band arrangements from the Chicago Theatre basement. Max Raabe spotted the sheet music for “I Won’t Dance” (accession no. 100629) among the library’s 26 arrangements of songs warning “I Won’t,” 106 assuring “I Don’t” and 124 demurring “I Can’t.”

Chapter 2: NSFW (Not safe for Weimar) — Americans conquer Berlin’s Admiralspalast

In the beginning of the ’20s, the owner thought, “OK, let’s make a cabaret or a review theater, because that is up-to-date and we have to be on top of the tastes of the time.” Many revues were started in the Admiralspalast.

I heard the name “Admiralspalast” the first time from my grandmother. My grandmother was a young lady and was visiting friends of hers in Berlin. She came from the countryside and she went into the Admiralspalast, sat somewhere in the balcony and suddenly a whole ballet [troupe] jumps onstage completely naked, only wearing bananas.

That was the time of Josephine Baker, so the ballet took the style of Josephine Baker and built a whole ballet. My grandmother was shocked and she wasn’t able to tell folks at home she was in the Admiralspalast, so whenever I’m onstage in Admiralspalast, I always think of my grandmother, who sits somewhere in the balcony — full of charm, in a red hat — shocked by a ballet just wearing bananas.

Now her grandson is standing there in tails and singing.

At the CPL: Crosstown rivals. In May 1925, Philadelphia bandleader Sam Wooding and Brooklyn songstress Adelaide Hall packed Berlin’s Admiralspalast with the “Chocolate Kiddies” revue; then in January 1926, St. Louis native Josephine Baker headlined “La Revue nègre” across the Tiergarten at Nelson-Theater. Read recollections of this vibrant, challenging and debated era in the biographies Underneath a Harlem Moon: The Harlem to Paris Years of Adelaide Hall (call no. ML420.H1166W55 2002) and Josephine: The Hungry Heart (call no. GV1785.B3B35 1993).

Chapter 3: End of a Berlin era — “Show us the way to the next whisky bar”

Our audience knows what it means if I say, “This song, written in 1928” or “Written in 1932.” They know, one year later, maybe the composer and the lyric writer had to leave the country.

The humor of the time was very Jewish. And the songwriters and lyric writers were very often Jewish.

The Jewish composers wrote the songs to entertain an audience. I want the Jewish composers and lyricists to be honored for their works and not for them to be reduced to their destiny.

At the CPL: Quantum mechanics. The more sheet music Raabe discovers here, the better his Berlin band swings. Max Planck, Berlin’s pioneering physicist of the 1920s and 1930s, might have observed that the energy (E) of Palast Orchester recordings is proportional to the frequency that its singer visits (v) Chicago’s library:

E = mv … where (m) is Max Planck’s Max Raabe constant.

For a taste of the electromagnetic waves that Planck, the father of quantum theory, tuned in over Weimar radio, try Raabe and the Palast Orchester’s live recording “Heute Nacht Oder Nie” (“Tonight or Never”) (call no. M1735.18 .M39 2010).

Chapter 4: The rise of the Third Reich

And then the Nazis came to power and [Berlin] changed completely again. A huge culture in Germany and Berlin was destroyed. Germans killed their neighbors and came to be in a horrible and very dark part of a middle age — I can’t explain how horrible.

Max Raabe and the Palast Orchester were the house band in Bavarian filmmaker Werner Herzog’s “Invincible” (2001), set in 1930s Berlin.

I said to Mr. Herzog, “You know, when the Nazis are making terror in this theater — in this revue theater where the orchestra is playing night by night — it would be nice if I could do something to help, so it’s clear for my grandma and my parents that I’m on the right side of the people.”

And Herzog said, “OK, you get a table and throw the table onto the head of a few Nazi idiots.” And I said, “Yeah, OK, this is nice.”

So they took a table — prepared one from paper or plastic — and this table was so easy and light, it was like a feather. It looked so stupid and everybody was laughing, even the Nazis in the scene. And then we said, “Let’s forget it. Nice try.”

At the CPL: Laughing, uncomfortably, at movie Nazis. Raabe’s favorite film is Ernst Lubitsch’s darkly humorous “To Be or Not to Be” (1942). Lubitsch, a Jewish native of Berlin who became the toast of Hollywood in the 1930s and ’40s for his sophisticated comedies, pairs Jack Benny and Carole Lombard with a farcical Warsaw theater troupe as Germany readies its 1939 invasion (call no. PN1997 .T612 2005).

Chapter 5: Walled Palast, divided city

I visited [East Berlin] in the ’80s. I lived in the west part of Berlin and it was possible for West Germans to go to the east part. Everything was very cheap for students.

The big, famous theaters were in the east part and I went to theaters and opera houses to see different musicals or theater plays. I was in the Admiralstpalast when it was called Metropol-Theater.

Everything [I saw in East Berlin] was very serious and very dark. Everything was pathos and every word was very heavy stuff. I think they also brought funny pieces but by chance I think I got only the heavy ones and the deep, depressive pieces. That was strange for me.

It was almost like time-traveling when you went to the east part of Germany. Streets were empty, everything was gray and sad. It was like turning back to the ’60s in West Germany.

Chapter 6: Keeping the world outside

But, believe me, West Berlin in that time was gray as well, very gray.

Wagner was my thing when I was 16, 17, 18 — something like that — and after that I changed to other composers, and I was finished with my opera intentions. I listed to Schubert lieder and Brahms and chamber music. That was my favorite music. Opera wasn’t interesting anymore.

I am through with Wagner since I was 18. I am fine with him but it was a very short, strange period when I was alone with my headphones and the libretto on my knees and keeping the world outside.

Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau was very important in that time for me, and we have wonderful lied singers now in Germany. I prefer the baritone for this repertoire because I’m a baritone.

The other music when I grew up, when I was a teenager and we were hanging around with friends, was Frank Sinatra — and my favorite, always, was Mel Tormé.

At the CPL: Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau and Melvin Howard Tormé. Fischer-Dieskau, the Berlin baritone born in 1925, lent definitive interpretations to Franz Schubert’s song cycles (call no. M1620.S35F5 1985). Tormé, a samt-nebel doppelgänger born the same year on Chicago’s South Side, favored Shubert Alley over Schubert lieder (call no. M1506.T67M44 P34 1984).

Chapter 7: “We’re more than just the two of us now. We embody something.”

I lived in Kreuzberg and I lived in Neukölln and I always walked the same way from Neukölln to Kreuzberg. Years later, after the walls came down, I went to my old place in Neukölln and walked the same way I’d always walked along that wall. It was like in a film — you see that area you know and suddenly something is completely different. It’s gone. The whole wall was gone.

At the CPL: inside the library, outside the wall and over the bridge. Ageless Swiss actor Bruno Ganz wearies of aging cabaret legend/émigré Curt Bois wandering through a black-and-white library, so Ganz, as the film switches to Technicolor, takes a stroll through West Berlin’s gritty Kreuzberg neighborhood in director Wim Wenders’ prophetic 1987 ode to his divided city, “Wings of Desire” (call no. GERMAN FICTION).

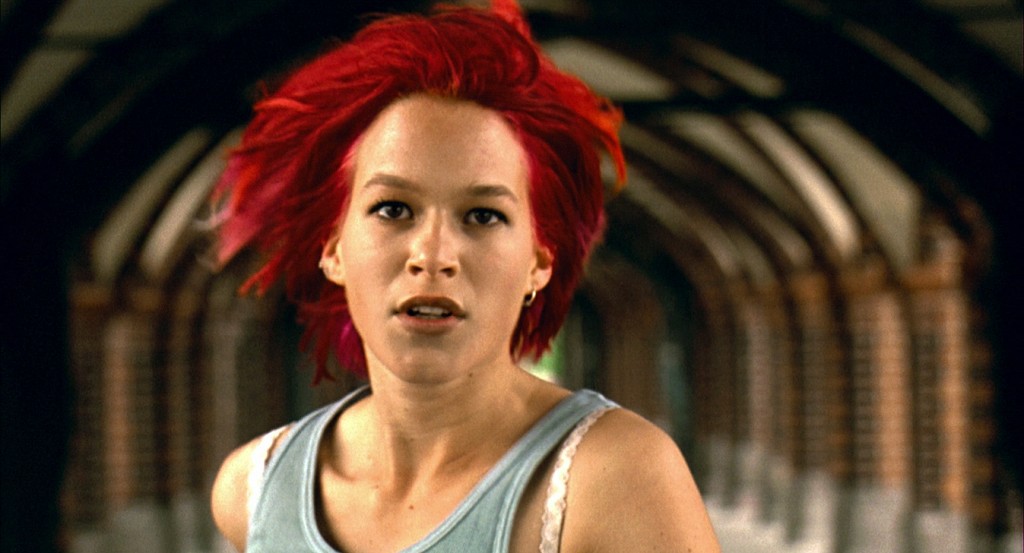

Fast forward a decade to Technicolor-hued actress Franka Potente, racing across the Oberbaum bridge, from Kreuzberg and toward stardom, too young and rushed to recognize Berlin’s once-fortified Cold War crossing. (“Run Lola Run” is call no. PN1995.9.F67 L65 1999.)

And so it is everywhere. You walk and suddenly you realize something’s changed.

I’m visiting the same theaters as in the ’80s but they’re playing completely other things. To me, it’s the same theater and the same architecture inside and outside but it’s a totally different atmosphere. It’s another audience.

For me, it’s not the same city. But it is, of course.

Andrew Huckman is a Chicago-based lawyer and writer.