Transcript of the Commencement Address

by Riccardo Muti, Music Director of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra,

at the DePaul University School of Music, June 15, 2013,

on the Occasion of Receiving an Honorary Doctor of Humane Letters Degree

First, I have to thank all of you — the Reverend President, the Dean, all the teachers, the students — on this fantastic day they will remember forever, your friends and relatives and parents.

It’s a great day for you, and it’s a great day for me because, as of today, I will be a part of this great university. Always, on other occasions like this moment when you receive an honorary diploma and then have to say something, it’s difficult because it’s a moment of joy, and the boys and girls, parents, and teachers want to enjoy it, and always they are afraid the honorary graduate will say some boring things! Generally, everyone wants to show how knowledgeable and cultivated he is. But I have not prepared anything. (Laughter and applause.) So you will not be bored by philosophical, theological, social, musicological speeches.

But because I was a young a person like you, I thought that maybe in these few minutes you would be interested in knowing who this man is, who all his life waved his arms. This can be for many reasons. One reason is that to play an instrument or to sing is much more difficult than to move the arms. (Laughter and applause.) In fact, my teacher, who was the assistant to Arturo Toscanini at La Scala, when we had technical problems, he said, “Don’t worry, you do this [waves his arms], something will happen.”

I was born in Naples. (Cheering.) Un momento, not Naples, Florida. (Laughter.)

My father was a medical doctor. And we are five brothers, and my father, who had a beautiful tenor voice, introduced all of us to music. He thought that even if we were thinking in the future to pursue other professions like to be a doctor, lawyer, engineer, etc., everybody must be educated in theater and music. And that’s the reason why when I was 7 years old, at Christmastime, when generally everybody in Italy and around the world we find some toys or some gifts outside the door, I opened the door and I found as a gift a small violin, which, for me, was a moment of terror. (Laughter.) Because that meant I had to work.

And, in fact, I remember that I started to study this violin because my father really wanted us to study music. And generally, I preferred to stay near the window where, in front of the window, I could see my friends playing football [soccer] or playing this or that and I was doing [makes motions of playing the violin]. And I was so bad, making the life of everyone around me miserable with these sounds, that one day my father said to my mother, “You know, the boy really is against music, he is absolutely a disaster.”

In fact, the professor of solfeggio [ear training] for three to four months was trying to convince me to read the notes on the pentagram because I didn’t want to learn. And so when she came and said, “What is this note?” I just guessed “fa, mi, do” and one time in 20, I found the right note. (Laughter.)

But then suddenly something happened; I don’t know what. But overnight, immediately I started to love music. And I made progress very, very quickly. And in the famous solfeggio, I became so good that even now at my age, I am able to do, for example, the presto of Leonore No. 3 of Beethoven. Do-sol-fa-mi-re-do-si-la… (Very fast solfeggio — audience whoops and claps in response.) I spent all of last night practicing this for you. (Laughter.)

And then because I was living in a very small town on the Adriatic where my father was the doctor, playing the violin, beautiful, yes, but I needed somebody to play the piano together with me. And it was difficult to find a young pianist to play with me, so then I started to study the piano. And then I realized that the melody (indicates right hand) and the accompaniment was there (indicating left hand) that I could do it all by myself, so I abandoned the violin and I started the piano.

Then I went to the conservatory but in the morning I went to the school for classical studies because my father would not give the permission to study only music because he was afraid that a musician, being from the south of Italy … where do you go? Then I studied piano in the afternoon and classical studies in the morning.

One day the director of the conservatory in Napoli said to me, “From the way you play the piano, I think that you have the nature and qualities to be a conductor.” And until that time, I had not thought to be a conductor at all. And so I tried, and it worked. After a few minutes, where it was strange that I was doing this and doing that (waves arms), doing nothing while the others were producing the sound … I thought it was very convenient.

But the director of the conservatory said, “You have qualities, but now you have to study composition.” So I had a degree in piano and studies in composition. In Italy, the study of composition is 10 years: four years of harmony, three years of counterpoint and three years of orchestration. So I did 10 years in five years. I had a diploma, and then I won the Cantelli international competition, and my career was made by the orchestras — not by important people, managers, agents, etc.

You have to remember, as Christ said, “Estote parati” — you must “be ready” because destiny knocks at the door of everyone at least once in a lifetime. But in that moment you have to be ready to answer. Be ready, be ready.

I had an opportunity after winning the competition. I was invited by the theater in Italy to work with Sviatoslav Richter, one of the giants among pianists in the ’70s and ’80s. People of the theater asked him, “We have a very young, unknown conductor. Are you willing to play with him?” He said, “If he’s a good musician, why not?” But then he wanted to see me, not to see my face but to see what kind of musician I was.

And because he had a recital in Siena in Tuscany, he called me to go to see him. And I thought, “It’s impossible he wants to just see me as a person; he wants to see me as a pianist, as a musician.” So I prepared the Mozart Concerto in B-Flat and the Britten Concerto — the orchestral part — thinking he wants to play with me.

And I arrived in this huge hall of the academy in Siena that is very old. I found when I opened the door two huge grand pianos. He was standing at one of the instruments and motioned for me to sit at the other piano. And we played together — he the part of the soloist and me the part of the orchestra. And he said to me, “If you conduct the way you play, then you are a good musician, so I will give you this chance.” After the concert, the orchestra asked me to become their conductor because they were without a music director. This happened in Florence, in London, in Philadelphia, in La Scala and in Chicago also.

At a certain point I realized, that for many years when you are young and have to make this horrible word, a “career,” you play music especially for you, to have success, the applause — and this is natural, no? But at certain point in life, to make a good performance of a Brahms or Beethoven symphony is important because you develop. The music makes you think and makes you better if you go deeper.

At a certain point I read a certain phrase of Mozart. Mozart said, “The most important and deep music is the music that lies between the notes.” It’s a very deep thought. Between the notes is the universe. Behind the notes is the infinite. So when we say we understand a composition, what we understand — we understand the technical, we understand the architecture, harmony, the counterpoint, the timbre, the dynamic, the concrete part of the music.

But the message behind it is impossible to understand. You can feel it. That’s the reason why music is extremely important in putting people together. The message that is behind the notes is universal and that’s the reason why Mozart, Beethoven, Verdi, etc., they are understood or they speak to people in the United States, in Italy, in Australia, in China, in Japan, in South America.

Not only that, the music brings people together. Almost 20 years ago, I had the idea of doing a concert every year — a concert for friendship — bringing together people, bringing music to troubled cities that have very serious, traumatic and sometimes tragic problems. The first concert was in Sarajevo where the city was completely destroyed and there was nothing. The first thing they wanted was music.

Like in 1946, after the Second World War when Milano had been bombed, the first thing the people wanted rebuilt was the theater, La Scala, the symbol of the city. Toscanini came from the United States to reopen this glorious theater.

So in Sarajevo, the stadium had more than 9,000 people crying. We had invited some of the musicians from the Sarajevo symphony to join the Italian musicians, to play together. We arrived and these musicians, many of them were without instruments or with destroyed instruments, and we gave them instruments, and they sat near the Italian musicians with different religion, language and culture. They didn’t know each other’s names, and they sat together and their hearts were beating together in the same way, with the same feelings. What diplomacy couldn’t do, music created. That’s the reason you, friends, have a mission. You have embraced culture. You must use culture, music and theater to bring people together. The world today is extremely problematic. Blood is everywhere. People don’t seem to understand each other. But I can tell you as I conclude that you, young and cultivated people, through your world of music and theater, can help your nation and the world become better.

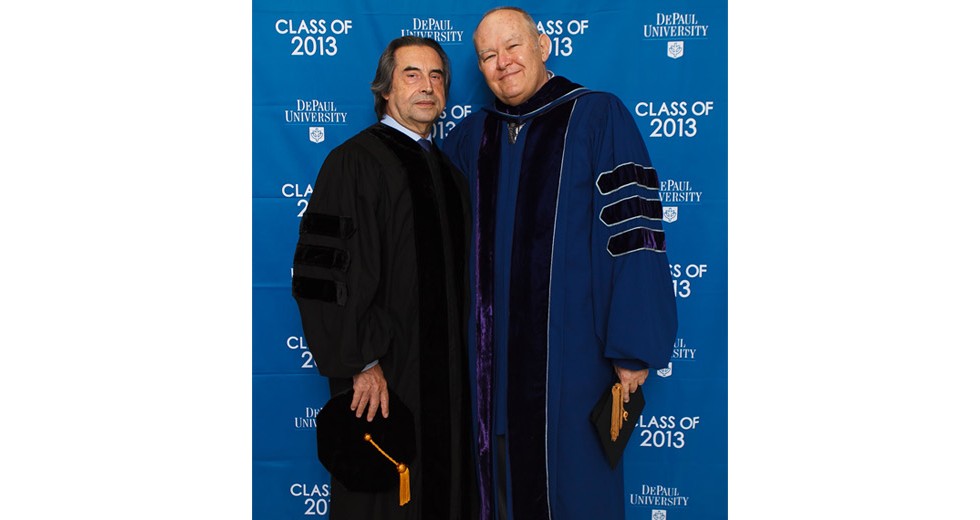

PHOTO: Riccardo Muti (left) with Donald E. Casey, dean of the DePaul University School of Music.