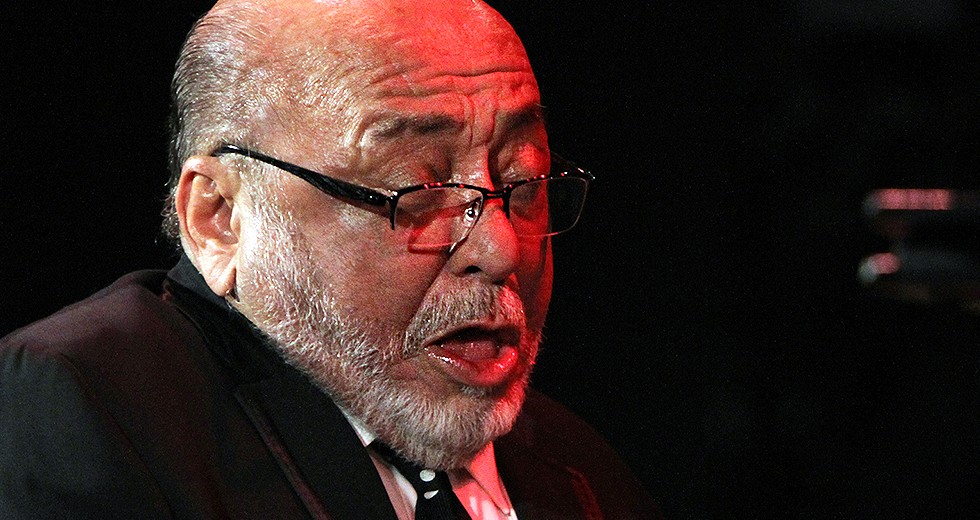

Most of the Western world follows the Gregorian calendar but Eddie Palmieri adheres to what could be called the Jazz Greats timetable: “After you hit 50, you just go by the years over the 5-0 mark, so by that measure, I’m 28.”

OK, so the venerable pianist-bandleader turned 78 in December, but who’s counting? After six decades in the music business, beginning with his professional breakthrough in 1955 with the Johnny Segui Orquesta, continuing with his landmark octet La Perfecta in the ’60s and leading various Afro-Cuban jazz bands since then, Palmieri is. “I’m working on four discs now right now,” says Palmieri, who will perform with his septet Jan. 16 in a Symphony Center Presents Jazz series concert. “At 78, I don’t have much time left,” he adds, punctuating the remark with laughter. “So I have to work fast.”

Two discs will be big band productions, with the third featuring a more intimate Latin jazz lineup, and the fourth a collection dedicated to his wife of more than 40 years, Iraida. “One of the big band discs is going to be called ‘Concentrated Power,’ featuring 2o of the best musicians in the world,” he said. “It’s going to be a lot of fun.”

More numbers: with a discography climbing past 40 studio albums, Palmieri emphasizes they all display the sense of excitement that has become his trademark. “If there’s any iota of wisdom that I have, it’s that I don’t think my music might excite you; I know it will,” he said. Over the years, those albums have brought him nine Grammys, with the most recent awarded in 2007 to “Simpático,” recorded with longtime collaborator, trumpeter (and Urbana native) Brian Lynch. “Then when I realized that I had nine Grammys,” Palmieri adds, laughing, “I had to get another one for the other thumb.”

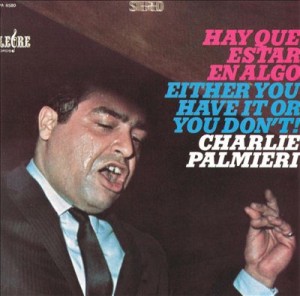

Eddie’s older brother, Charlie, was a major figure on the NYC Latin music scene of the 1960s to the 1980s. Here’s the cover of a boogaloo-influenced disc, released in 1967, by Charlie Palmieri on the Alegre label.

That 10th honor came in the form of the Latin Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award, which he received in 2013, just months after being designated as an NEA Jazz Master, the highest accolade bestowed on American jazz musicians. His fellow honorees that year consisted of pianist-composer Mose Allison, saxophonist Lou Donaldson and jazz impresario Lorraine Gordon. At the ceremony, he accepted his award from fellow piano legend McCoy Tyner, whom Palmieri regards as his greatest inspiration, along with pianists Thelonious Monk and Eddie’s older brother, Charlie, an influential Afro-Cuban stylist (whose career was cut short by a fatal heart attack in 1988).

Though by any measure, Palmieri’s music is steeped in jazz, he doesn’t consider himself a “jazz pianist.” Beginning as a drummer, he “always had a percussive approach to pianism,” he said. “I went into the dance band genre, but my harmonic structures are all based on jazz harmonics,” he said. “At the same time, it’s an honor to be categorized with all of these jazz greats, like McCoy Tyner [a 2002 NEA Jazz Master] and Count Basie [a 1983 Jazz Master].”

Born in the Bronx to Puerto Rican parents, Palmieri always has felt that his “heart belonged in Cuba.” “My sound evolved from Cuban music of the ’40s and ’50s — a great sound that has been lost to time.” He’s encouraged that the United States might finally restore diplomatic relations with Cuba — a deal largely brokered by Pope Francis, the first Latin-American pontiff (and a fellow Sagittarian — Palmieri and the pope share the same birth week). But Palmieri doesn’t hold much hope that Cuba will return to the artistic glory that gave rise to the mambo, charanga and cha-cha. “I still feel the sadness caused by the economic conditions in that country all these years,” he said. “That’s the reason I didn’t ever go to perform in Cuba. I respect Cuba. It lives in my heart and in my music. To see the country that put the world to dance in its current state is heartbreaking.”

Still, the Schoenberg of Salsa, as he’s sometimes called, remains upbeat. That nickname comes from Palmieri’s adherence to the mathematically based Schillinger System of Musical Composition. A Russian mathematician who arrived in the United States in 1928, Schillinger had several famous students, including George Gershwin, Oscar Levant and Benny Goodman. “The key to Schillinger’s method is building tension and resistance,” Palmieri said. “What Schillinger helped me to understand is that there is a way to engineer excitement through musical structure. In sex, we call that an orgasm. In music, it’s the highest degree of climax. You forget all of your problems when you’re dancing. You forget all of the worries of the world.”