Count Kent Nagano among the many musicians whose lives were transformed by the generosity and genius of celebrated conductor-composer Leonard Bernstein. He met “Mr. Bernstein,” as he respectfully calls him, in 1984, and he remained a kind of informal student until his mentor’s death in 1990.

Because of Nagano’s close relationship with Bernstein, Chicago Symphony Orchestra officials asked him to include one of the composer’s works on his March 29-31 programs as part of the orchestra’s seasonlong celebration of the creative titan’s centennial. “I was, of course, very happy to think about it,” said Nagano, 66, who has held such prestigious positions as artistic director of the Deutsches Symphonie-Orchester Berlin and music director of the Los Angeles Opera. He now serves as music director of the Montreal Symphony Orchestra and general music director and chief conductor of the Hamburg State Opera in Germany.

At the time the CSO reached out, Nagano happened to be reading W.H. Auden’s Pulitzer Prize-winning poem, The Age of Anxiety. That brought him back to Bernstein’s Symphony No. 2 for Piano and Orchestra, The Age of Anxiety (1948-49), which he was thinking of returning to his repertory. “It was interesting timing,” he said. “I asked if they would consider it, and they did.”

Overlapping with Nagano’s time with Bernstein was the latter’s recording of Wagner’s opera, Tristan und Isolde, with the Bavarian Radio Symphony in Munich. Nagano also has strong ties to Munich, and he felt the Siegfried Idyll, Wagner’s symphonic poem for chamber orchestra, would be an ideal coupling with the symphony. Among other things, he said, both works use simple elements in a highly sophisticated way. As a “counterpoint” to those two selections, Nagano chose Schumann’s Symphony No. 1 (Spring). “Schumann has always been a mainstay in my repertoire,” he said.

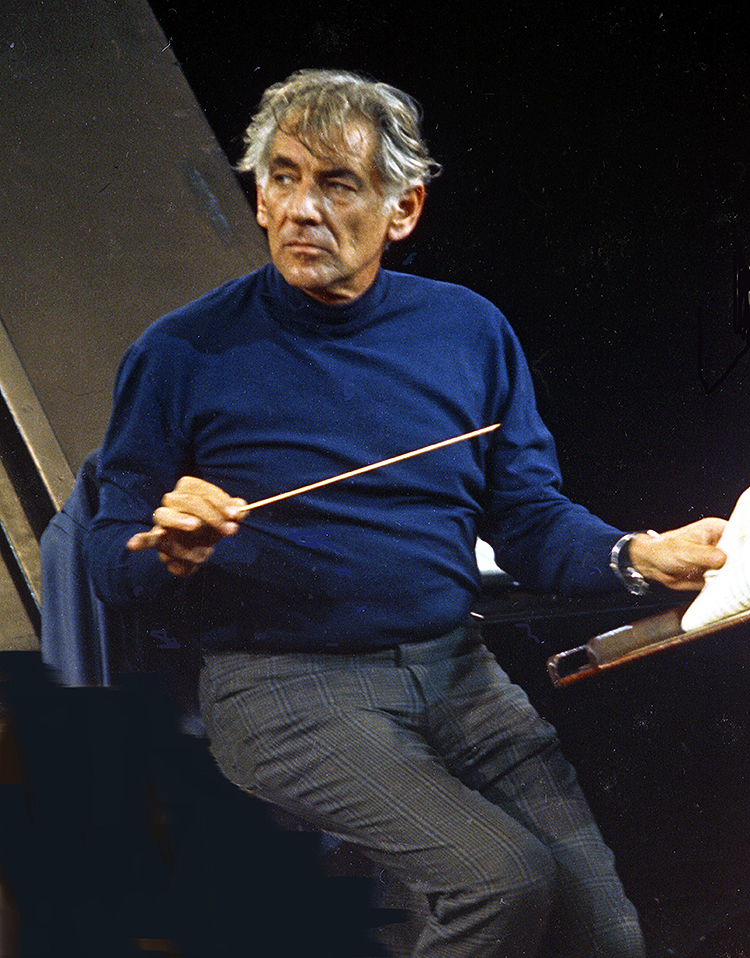

Three decades after the death of Leonard Bernstein, Kent Nagano says, people “can see what a great composer, what a great artist he was.” | Photo: Allan Warren/Courtesy of the Leonard Bernstein Office, Inc.

While studying with French composer Olivier Messiaen, Nagano began working with conductor Seiji Ozawa, who conducted the 1983 world premiere of the composer’s St. Francis of Assisi at the Paris Opera. Ozawa in turn introduced Nagano to Bernstein at the Tanglewood Music Festival in Lenox, Mass., where the composer-conductor taught and performed every summer. As a recipient of the Seaver/National Endowment for the Arts Conductors Award, Nagano had a broad range of “open-ended and multifaceted sessions” with Bernstein that included studies of scores side by side at the piano, attendance at the older conductor’s rehearsals and extensive discussions before and afterward. In addition, he went to art museums and theatrical productions with Bernstein, who had little time for the barriers that too often distance artistic disciplines.

“Probably what made that period most fascinating is that at the same time I was working very closely with Pierre Boulez,” Nagano said. “At least from the outside, it was an unusual combination of teachers to be working with at the time, but as it turned out for one who was working so intensively and closely with both, it was the similarities that were most striking — both, of course, exceptional composers, exceptional thinkers and both deeply cultivated.”

Nearly 30 years later, he stills draws on the lessons that he learned from the two mentors, emphasizing that it was a “stimulating time.”

It is perhaps hard to remember now, but at Bernstein’s death, there was extensive debate about his place as a composer. While most experts agreed that he would always stand as one of history’s greatest conductors, his compositional legacy beyond just a few works like West Side Story or Candide was questioned. Bernstein’s reputation was still clouded by his refusal to fall in line with the serialism or atonality that dominated much of classical music in the middle to late 20th century and by the unusual structure and mixed style of some of his works. But in the years since, Bernstein’s reputation as a composer has steadily risen, as evidenced by the thousands of performances of virtually everything he wrote by artists and ensembles worldwide as part of his centennial celebration.

“It takes a certain amount of time to have a perspective on things,” Nagano said. “During Mahler’s lifetime, he was so celebrated and renowned as a conductor that it in some ways overshadowed his gifts as a composer. Now, today, there’s no one who remembers seeing Gustav Mahler conduct, but we certainly know him through the great masterpieces he left behind. With the benefit of time, quality can be allowed to rise above political discourse, because people forget the politics when you take it out of context, and what is left is the creative work of the artist. And it’s on that creative work that a consensus gradually comes into focus.

“Now, in the 21st century, it’s not only Leonard Bernstein, it’s fascinating to see that the 20th century, which was accused of just being so experimental and having ruptured with the great traditions of the 19th century and before, to see that the 20th century is proving itself to be one of the most colorful and richest centuries in terms of contributions to the standard repertory.”

In the 1980s, three of the composer’s late works drew particular controversy: the musical 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue (1976), the opera A Quiet Place (written in 1983 and later revised) and Mass (1971), commissioned for the opening of the Kennedy Center in Washington, D.C. “The discussion was very active and passionate and both positive and negative,” Nagano said. Through his conversations with the composer, he knew that the development of Bernstein’s compositional language was deeply embedded in these works, but it required time for performers to probe and fully understand.

After Bernstein’s death, Nagano felt a responsibility to keep these works alive. He admits that he was not completely moved by them at first, but he had enough faith in his mentor to believe that if continued to study them, they would slowly reveal themselves to him. “That is certainly what happened,” he said. Nagano went on to record all three, and he has remained a devoted champion of Bernstein.

In the 28 years since, attitudes about his music, especially his later works, have changed significantly. “People, now with this perspective,” Nagano said, “can see what a great composer, what a great artist he was.”