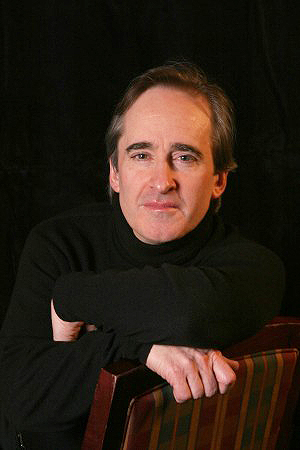

James Conlon’s Flying Dutchman concert with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra at Ravinia had an unmistakable air of finality, and, on one level, that made sense. It was, after all, the famed American conductor’s last appearance as music director of the revered summer series, an occasion that was celebrated with a video and a special souvenir book saluting his 10-year tenure. But in a broader sense, there was nothing really final about his appearance at all. He plans to remain as busy as ever, with perhaps a little more time off in the summers, and he will return to Chicago to lead the CSO in subscription concerts Dec. 17-19 at Symphony Center.

That said, Conlon acknowledges the emotions that swirled around him on that memorable night, Aug. 15, at Ravinia, when the audience gave him a sustained response before he had conducted one note. “Yes, it was gratifying to receive a standing ovation before starting the performance,” he said via e-mail. “It always is, of course, but this had a special meaning for me. I was surprised by the video that was shown before the performance as well. What was not a surprise was the quality of the performance of The Flying Dutchman. All of the elements ripe for success were there: the Chicago Symphony Orchestra and Chorus and an excellent cast. But I think it was one of those occasions where the whole was even greater than the parts. I will certainly not forget it.”

Before his Ravinia departure, Conlon, 65, had signaled that he was ready for some changes, and that is exactly what he has undertaken. In addition to leaving his position at Ravinia, he announced in February that he would step down in 2016 after 37 years as music director of the Cincinnati May Festival, the oldest continuously operating choral festival in the United States. But along with those departures came something new as well — his appointment in June as principal conductor of the Orchestra Sinfonica Nazionale della Rai in Turin, Italy. He will be the first American to hold the position in the 84-year history of the official ensemble of Rai (Radiotelevisione Italiana), the Italian public broadcasting network. The appointment, which begins in 2016-17, calls for the maestro to lead eight weeks of programs, including tours, recordings, concert operas and choral works. But he will already conduct three weeks of subscription concerts this season with the orchestra, and has begun planning for his upcoming projects there.

In addition, he will remain at the Los Angeles Opera, where he has been music director since 2006, and continue his guest conducting around the world. Indeed, Conlon ticked off a list of engagements in 2015-16 that he is eagerly anticipating. “I’m very happy to return to the CSO downtown,” he said, “which will be a new chapter in our collaboration; happy also to return to the San Francisco Symphony and the Orchestre National de France in Paris. Operatically, I am especially looking forward to conducting Mussorgsky’s Khovanschina at the Vienna State Opera [his debut there], as well as two operas for the first time, Jake Heggie’s Moby Dick and Bellini’s Norma, both at Los Angeles Opera.”

On whether his priorities had changed as he moves into this new stage of his career — composers he wants to spotlight or postponed projects he hopes to realize — Conlon demurred. “I don’t think in terms of career stages or priorities,” he said. “My major and all-consuming interest is to make great music to the best of my ability wherever I am.”

One thing he is keen to continue is his four-decade relationship with the CSO. For his December appearances, he is leading a program of mostly little-known works, including two tone poems by Antonín Dvořák — The Golden Spinning Wheel and The Wild Dove — that received their American debuts in Chicago in 1897 and 1899, respectively. Their presentation is part of the CSO’s celebration of its 125th anniversary during which it will revisit some of the world and American premiere works it has performed over its venerable history. Conlon received a list of such works to choose from, and the two by Dvořák jumped out at him. “I particularly love Dvořák, and there are many beautiful pieces [by him] that are not heard often enough,” he said.

The program also will feature the CSO’s first performances of Czech composer Jan Křtitel Vaňhal’s Double Bass Concerto in D Major, with principal bassist Alexander Hanna as soloist. Starting off the evening will be the overture to Mozart’s to Lucio Silla — another first for the symphony. “I think the overture is a great piece,” Conlon said. “It is a very early example — Mozart was only 16 when he wrote it — of the three-part overtures that resemble a short symphony.” (Chicago Opera Theater will perform the complete work in performances Sept. 26 and 30 and Oct. 2 and 4 at the Harris Theater for Music and Dance, 205 E. Randolph.)

Conlon’s career is taking off in some new directions, and he is going to try and take a bit more time off, but his international presence is likely to be as strong as ever, and Chicagoans can still expect to see him back here on a regular basis.

Kyle MacMillan, former classical music critic of the Denver Post, is a Chicago-based arts writer.